Watch: David Letterman: The Late Night Television Anti-Hero

If you were alive in the 1980s and you turned on NBC at

12:35 AM,

the very last activity you would have seen David Letterman doing on

“Late Night” is fawning over baby pictures—as he did during his final

days of public life.

In fact

Letterman was TVs first and now its last grumpy old man, except he was

in his thirties at the time and looking at this video essay, it’s hard

to believe a guy this thorny, someone who spent

this much time torching his bosses and ripping away at a pretentious

celebrity modus operandi—could be on television for more than three

minutes, much less over 30 years.

How does one explain his success?

In interviews

Letterman likes to give all the credit away for his success to his hero,

the great Johnny Carson, and more than occasionally, he even

acknowledges the influence of Steve Allen, the first helmsman of that

NBC institution known as the Tonight Show and perhaps its most talented

performer. (Before anyone insists Jimmy Fallon takes the crown on this

point, take a look at Steve Allen’s “Meeting of Minds,” which he created

and wrote for PBS, and tell me if our latest occupant of Tonight could

pull off something so erudite.)

While

Letterman’s approach to late night TV may have channeled his

predecessors in certain ways—like Letterman, Johnny Carson could

belittle and destroy his guests in a single sentence—the Letterman who

rose to cultural prominence at the end of the Cold War was a singularly

crass, awkward, slightly misogynistic, fearless truth-teller.

And that’s why we loved him.

Letterman’s

eternal brilliance lies in his expansive mastery of the components of

humor: the set-up and the punchline, i.e. the story and the funny

climax.

First, unlike

the 2015 version of himself, Letterman in the 1980s was absolutely not a willing member of America’s celebritocracy—that cult of celebrity

which had always been a large part of show business culture.

But, what

Letterman possessed from the beginning was an uncanny ability to search

for comedic set-ups in visual, verbal and intellectual spaces where no

other performer thought to look. He was intelligent, well read and

lightening fast. Any sentence uttered—stupid or intelligent—on “Late

Night with David Letterman” could be made a slave to his opportunistic,

devastating punchlines—with emphasis on the word “punch.”

And it didn’t

matter who you were—network executives, respected celebrities, stupid

humans, stupid pets and his most prolific target of all, Letterman

himself. No wonder Cher called him an asshole. No one was safe.

Before he

leaves for good, one must acknowledge his huge influence. “Late Night

with David Letterman” taught an entire generation not only how to search

for the perfect comedic set up but also what it means to deliver a

foolproof punchline. In college I watched this sweet anarchy day after

glorious day, as the comedian casually lobbed stick after stick of

verbal dynamite into the key light biosphere, this wanton behavior

continuing unabated for a decade and a half.

But, young

David Letterman was not stupid. He understood himself and his audience

extremely well, and he walked the line between hero and anti-hero,

between TV pioneer and social pariah for as long as he could and as he

aged and matured, he even knew when to step away from that line.

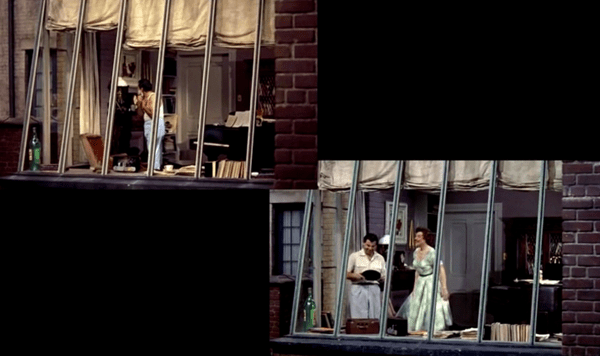

So, here he

is again in full “Dave,” before the anti-depressants, before the lessons

of the sex scandal, before the birth of his son Harry, before his

heroes had ascended to the next life and left him alone.

I was recently waiting in line at the post office.

The lines are

long these days at the busy location in central Plano, Texas because

that branch has staffed down, and one can be sure that sending a parcel

these days is a deeply boring and cynical experience as an impersonal

staff and an uninterested system wastes your time and pisses you off.

A half hour

or so later, I had placed my package in the system, and I was walking

toward the exit. I spied a middle-aged African-American man shaking

his head and sighing in frustration. He was at the end of a very long

line.

I walked up to him and extended a hand which he grasped as if it were a life line.

“The cocktail waitress will be around in a few minutes,” I said to him. “Buy yourself a rum and Coke. I hear they’re amazing.”

The man smiled and laughed.

For those of us who watched it, “Late Night with David Letterman” continues.

Serena Bramble is a film editor whose

montage skills are an end result of accumulated years of movie-watching

and loving. Serena is a graduate from the Teledramatic Arts and

Technology department at Cal State Monterey Bay. In addition to editing,

she also writes on her blog Brief Encounters of the Cinematic Kind.

Ken Cancelosi is the Publisher and Co-Founder of Press Play.