Watch: Hal Ashby, Filmmaker from the Edge of Darkness

Hal Ashby was an American filmmaker whose quirky sense of humor and sentimental charm made him a unique voice in the American New Wave. His work spans from 1970 to his death in 1988—for the sake of time, I’m going to concentrate on his string of classics between 1971 and 1979. Ashby got his start in the 60s as an editor and ended up earning an Oscar nomination for the 1966 Norman Jewison comedy ‘The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming’ and he won the Oscar one year later for another Norman Jewison film titled ‘In the Heat of the Night.’

Despite being older than the Vietnam generation, he was very comfortable living the hippie lifestyle, which was apparent even in his first film titled ‘The Landlord,’ about a wealthy white man who becomes the new landlord of an urban apartment building for low-income tenants. He plans to evict all the residents and transform the building into a home for himself. The film is a moving satire of race and class relations that still rings true today.

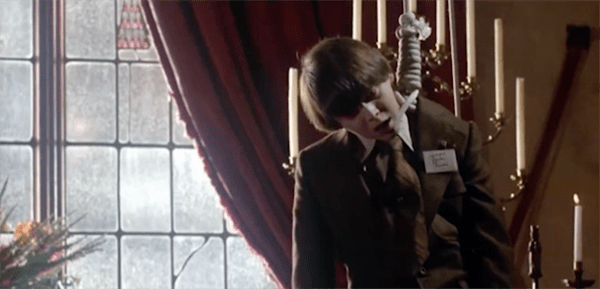

Following ‘The Landlord’ Ashby directed several iconic films starting with 1971’s ‘Harold and Maude,’ about a death-obsessed young man who starts a close relationship with an eccentric old woman. The screenplay for the film was the master’s thesis of a UCLA student named Colin Higgins. Ashby shot the film in and around the San Francisco Bay Area, which, coupled with a beautiful soundtrack by Cat Stevens, perfectly encapsulated the atmosphere of the youth culture during the early 70s and the theme of coming to terms with an existential crisis and feelings of alienation. Even though it was Ashby’s second feature film, it is widely considered to be one of his best, but that wasn’t the case at the time—after its release, it was a critical and commercial failure.

His next film, titled ‘The Last Detail,’ follows two navy officers as they escort a young sailor across a few states to a prison for petty theft. On the way they decide to show him a good time. Ashby was originally doing pre-production on a different film when Jack Nicholson told him about ‘The Last Detail.’ Ashby abandoned the project in favor of working with Nicholson. The script was adapted by acclaimed screenwriter Robert Towne from a novel by Darryl Ponicsan and was quite controversial when it was released due to its pervasive use of profanity. ‘The Last Detail’ captures Ashby’s unique charm and sentimentality and contains one of Jack Nicholson’s greatest performances.

His next film, ‘Shampoo,’ takes place during the 1968 presidential election and follows a male hairdresser—played by Warren Beatty—who uses his position to meet and have sex with women. A year later he made ‘Bound for Glory’—starring David Carradine— about folk musician Woody Guthrie who decided to travel west during the Great Depression. The film is most notable for containing the first use of Garrett Brown’s Steadicam rig, which provided smooth motion without the use of a dolly.

Ashby’s political themes started to take on a bigger role starting with his next film titled ‘Coming Home,’ which is about the Vietnam War, but doesn’t depict any combat whatsoever. Instead, it is about the veterans of that war coming back to America and coping with their injuries and the reality of what they did over there. It follows a recently paralyzed veteran who connects with the wife of a soldier at a VA hospital. The wife was played by Jane Fona who, along with her costar Jon Voight, won an Oscar for acting. Ashby also earned a nomination for Best Director. ‘Coming Home’ turns the media portrayal of the glory of being a soldier completely upside-down and shows the reality of what survivors face.

In 1979, Ashby made ‘Being There’ about a simple gardener who finds himself amongst the most powerful people in Washington who mistake his thoughts on gardening as profound metaphors. Chance the Gardener was brilliantly played by Peter Sellers in one of his most iconic roles. Ashby continued to make films until his death in 1988, but none were as beloved as his films from the 70s.

Films referenced:

‘The Landlord’ (1970 dir. Hal Ashby)

‘Harold and Maude’ (1971 dir. Hal Ashby)

‘The Last Detail’ (1973 dir. Hal Ashby)

‘Shampoo’ (1975 dir. Hal Ashby)

‘Bound for Glory’ (1976 dir. Hal Ashby)

‘Coming Home’ (1978 dir. Hal Ashby)

‘Being There’ (1979 dir. Hal Ashby)

‘The Russians Are Coming, the Russians Are Coming’ (1966 dir. Norman Jewison)

Tyler Knudsen, a San Francisco Bay Area native, has been a student of film for most of his life. Appearing in several television commercials as a child, Tyler was inspired to shift his focus from acting to directing after performing as a featured extra in Vincent Ward’s What Dreams May Come. He studied Film & Digital Media with an emphasis on production at the University of California, Santa Cruz and recently moved to New York City where he currently resides with his girlfriend.