I worked with HitFix.com television critic Alan Sepinwall at the Star-Ledger of Newark for nine years, 1997-2006. We shared the TV beat together throughout that period, writing reviews and features, and collaborating on a daily column of news and notes titled "All TV." The column was topped with a dual mugshot, photoshopped in a way that made it look as though two heads were growing from the same neck. Some colleagues and a few readers referred to that image as "The Two-Headed Beast," and as it turned out, the description referred to more than the mugshot. We truly were a team, and we yakked so much across our cubicle desks that we got shushed by everyone in the newsroom at one point or another. Most of the conversations were about the innovative things we were seeing on television during that fertile period, which brought forth The Sopranos (filmed right there in the Garden State!) as well as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Oz, Lost, Deadwood, The Wire, and other dramas that are now recognized as milestones in the medium's artistic development.

I originally set out to do a brief Q&A with Alan, but as anybody who's ever had the misfortune of sitting next to us in a newsroom can tell you, we're a couple of Chatty Cathies. The conversation ran nearly an hour. It has many digressions and tales-out-of-school, and a bit of playful teasing, yet somehow it managed to touch on the main themes and subjects of his book. I've reproduced our talk below, with some minor edits and omissions for clarity. — Matt Zoller Seitz

Matt: What are the factors that contributed to the existence of the dramas you describe in this book?

Alan: Cable was a big part of it—the fact that cable started looking to do more original programming. You remember when you were on the TV beat with me at the Star-Ledger, there were the major broadcast networks. There were UPN and the WB, sort of. And that was it.

And then HBO decided, “All right, we’re gonna get serious about this, and not just do one or two comedies a year.” And they became successful at it, and then others started imitating that. And at the same time, the audience started to really splinter, because there were so many viewing options, and it became easier to justify a show that does three or four million viewers a week.

Matt: How did it become easier for programmers to justify that? How did the economics work for them?

Alan: The idea is, if every show on the network is being watched by twenty million people or more, and you do a few shows that are only drawing three million, that’s harder [to justify], whereas that’s a good number for a cable network if the show is cheaper. A show like The Shield cost a lot less than, say, Nash Bridges did. That was part of it.

But there was also the fact that, as viewership overall started coming down, having three to six million viewers started to look a lot better than it might have in the days of Dallas.

Matt: Speaking of the days of Dallas, I’ve recently been revisiting some of the great shows, particularly dramas, from the ‘80s, such as Hill Street Blues and St. Elsewhere and Moonlighting, which was a show that, week to week, was as deeply nuts as Glee or American Horror Story. You never knew what you were going to get when you tuned in.

But something did happen. Something changed. Maybe it was the concept you discuss in your chapter on David Simon’s The Wire, the concept of "a novel for television." The idea that shows could be designed to be viewed in totality, at least on the back end. And there was not as much paralyzing fear that everything had to have a beginning, a middle and an end, tying up neatly within the course of any given hour.

Alan: That was definitely a big part of it. It was something David Chase was fighting against on The Sopranos. You can list all the different Sopranos storylines that began and then didn’t end, or didn’t end in the way we expected them to. A lot of it is just that you’ve got all these people like David Chase and David Simon and Tom Fontana and David Milch, who worked on these [network] shows in the ‘70s and ‘80s and ‘90s that were great shows. However, at the same time, their ambitions could only go so far, because they were beholden to a broadcast network model that aimed to draw as large an audience as possible. The thinking was, "You have to spoon-feed audiences to a degree. You have to give them case-of-the-week stuff.’

I love Hill Street Blues. I love St. Elsewhere. I wouldn’t say a bad thing about them. But there is a compromised nature to them that isn’t there in, say, Oz and Deadwood.

The Sopranos Effect

Matt: You deal with a lot of the influential pre-1999 shows—which is the year The Sopranos debuted—in your opening chapters, then you go into The Sopranos and move on from there. It seems to me you could easily have titled this book The Children of The Sopranos, because to some extent, even though a show such as Lost or Battlestar Galactica outwardly has nothing in common with The Sopranos, those shows wouldn’t have existed if The Sopranos hadn’t gotten on the air, stayed on the air, and been a hit.

Alan: That’s exactly true. A lot of the writers I talked to from Battlestar were writing on Deep Space Nine when The Sopranos came on. They all said, “We’re all going home at night and watching The Sopranos and thinking, ‘God, this is what we want to do!’” And they kind of got to do their version of it in the sci-fi realm. Damon Lindelof from Lost talked a lot about The Sopranos. He said that many of the influences on Lost were the same things that influenced Chase, like European film. The Sopranos made all these shows possible.

But then, Oz made The Sopranos possible—but without the commercial success that was ultimately going to lead to all those other shows.

Matt: What was the common thread in all these showrunners’ obsession with The Sopranos? It wasn’t the crime and violence, because some of these shows aren’t into any of that. Is it the postwar European cinema influence that you alluded to? Does it have something to do with the worldview, or the way in which the characters were portrayed?

Alan: It was all of those things. But it was mostly that, here was a show that was not beholden to any of the formulas that other people had to deal with in their [TV] day jobs, and them looking at The Sopranos and saying, “Wait a minute. You can do exactly the show that you want to do, you can make it intensely personal, make it really emotionally and narratively complex, you don’t have to treat the audience like they’re five years old, and you can still get millions and millions of people watching? Why can’t we try this?”

Matt: I was intrigued by the section in the Sopranos chapter where you and Chase get into the idea that, on The Sopranos, people don’t change. About a year after that show went off the air, I had an email exchange with Chase about my recaps of the show. It was cordial, for the most part, but he did take exception to my endorsement of the idea that The Sopranos was about how people don’t change. I didn’t mean it in quite the absolutist terms he thought I did, but he seemed sensitive to it, because it was a more depressing view of human nature than the one he meant to communicate.

But it seems that you got that impression, too. And we certainly weren’t the only ones. And, when you talked to him five years after the conclusion of the series, he still seemed concerned about that perception.

Alan: The ultimate version he gives is not that far removed from what you or I or other people thought, which is that on The Sopranos, people can try to change, but it’s incredibly, incredibly difficult to do so, and we saw a lot of examples of that on the show.

Matt: That’s a pessimistic view, but I wouldn’t say it’s an unrealistic one. How many times have you taken stock of your life and resolved to make some fundamental change, then ended up two weeks later wandering around blithely like Homer Simpson, going “La la la la”?

Alan: Can you think of characters on the show who tried to change their inner natures, and succeeded?

Matt: Yes. But unfortunately, those people tended to end up dead.

Matt: Yes. But unfortunately, those people tended to end up dead.

Alan: [Laughs] Yes! That’s what I’m saying. They hung themselves in the garage.

Matt: Like poor Eugene Pontecorvo. Or Vito, who has his sojourn in the gay Shangri-La of Connecticut, then returns to New York City and gets clubbed to death.

All in the Game: The Wire

Matt: Let’s talk about The Wire. You quote the HBO executive Carolyn Strauss as saying, “That show was at death’s door at the end of every fucking season.” I knew Simon had trouble after Season Three, but I didn’t know every renewal was that hard.

Alan: Well, a lot of people would argue that The Wire was a better show than The Sopranos was. But it was never as popular as The Sopranos. And it was in some ways more challenging. You could watch The Sopranos and think, “Oh, guys gettin’ whacked, people cursing, fart jokes,” and ignore the other layers. The Wire had a certain amount of violence and coarse humor, but it was a more difficult show. It has become much more popular in death than it was in life.

Matt: You point out that HBO sent out all of Season Four of The Wire to critics at once. That’s become common practice for certain types of shows nowadays, but it was unusual then, wasn’t it? [Note: At the time, networks did this for miniseries, but not for regular series.]

Alan: I talked to a lot of writers for this book, and not one of them could think of a case in which that was done before. The thinking was, “This is a show with a lot of characters and a very complex plot, people always react better to a series at the end of its run than at the beginning, let’s send the whole season out at once and see what happens.” Season Four of The Wire was the perfect season of a show to do that with, because of the whole story involving the kids. It’s probably my favorite season of the show.

Alan: I talked to a lot of writers for this book, and not one of them could think of a case in which that was done before. The thinking was, “This is a show with a lot of characters and a very complex plot, people always react better to a series at the end of its run than at the beginning, let’s send the whole season out at once and see what happens.” Season Four of The Wire was the perfect season of a show to do that with, because of the whole story involving the kids. It’s probably my favorite season of the show.

But that decision also speaks to what was happening at that time that was new. Doing a 10 or 12 or 13 episode order, finishing the whole thing and then sending it all out—a network couldn’t do that [before], because network shows made so many more episodes during a season, which meant shows were in production pretty much year-round.

Matt: You write of The Wire, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It isn’t designed like any TV show before it, not even the other early successes of this new golden age. It isn’t designed to be broken apart into bits, some parts elevated over others or consumed separately.”

For all the evolution that’s happened in American TV storytelling since The Sopranos, I can’t think of too many other shows that fit that description nowadays, Alan. There are exceptions. Treme, of course, but that’s a David Simon show. Sons of Anarchy is probably another one. The subject matter and tone on that one is more “pop” than on a Simon show. But I suspect that if you dropped somebody into season three or four of that show, they’d have no clue what the hell was going on—

Alan: There’s just such a Byzantine power struggle going on in that show. All the FX dramas have “Previously on Sons of Anarchy…” segments that seem to run almost as long as the episode.

Matt: [Laughs] Yes! You get near the end of a season of Sons of Anarchy, and you could cook a meal in the time it takes for them to get you up to speed on what happened previously. It’s not hard to see why there is resistance, even now, to this idea of television that has to be consumed and thought about in totality. Most of the shows that are devoted to that principle either have a small audience—which is the case with Treme—or they get cancelled after one season, which was the case with Rubicon.

Alan: I would say that Breaking Bad is a show in that vein. It took me till season three to fall in love with it in the way that I’m in love with it now, because—in much the same way as The Wire—it’s paced very slowly early on, it’s a different kind of tone than you’re used to, and you really need to see each piece built on top of every piece that came before for it to make sense, and for it to have the power that is has once you get to seasons two and three and beyond.

Alan: I would say that Breaking Bad is a show in that vein. It took me till season three to fall in love with it in the way that I’m in love with it now, because—in much the same way as The Wire—it’s paced very slowly early on, it’s a different kind of tone than you’re used to, and you really need to see each piece built on top of every piece that came before for it to make sense, and for it to have the power that is has once you get to seasons two and three and beyond.

The Whole and the Parts: TV in Totality

Matt: Would you say that of the current dramas, Breaking Bad is the one that most needs to be considered in totality? Or are there other shows that need to be watched that way?

Alan: I think Mad Men is a show like that. If you watch “The Suitcase” from season four onward, you’ll be able to say, “Yes, this is good acting,” but you won’t be able to appreciate it if you haven’t been watching four years of Don and Peggy building up to that moment. Game of Thrones, I think, is like that—and obviously that series comes from the world of books. In fact, I think there are certain ways in which the narrative structure of Game of Thrones is not ideally suited to television, where they’re bouncing around from place to place, but the series does try.

Matt: There’s an important difference, though, between Breaking Bad and Mad Men and, say, Game of Thrones, The Wire and Treme— which you get into to a certain extent in the book—which is that some of these dramas, no matter how complex their plots, do at least give you a character or characters that are definitely the leads. That gives you something to latch onto.

Alan: True.

Matt: Even on Sons of Anarchy, which is an ensemble show, they orient you by letting you know that it’s basically about the bikers—the issue of succession, of who’s going to lead the club. That was never the case with The Wire. You may have a central plotline that serves as a spine for a whole season, but that was truly an ensemble show, and even the way the show was structured was extremely rigorous, almost off-putting. These characters and this subplot get two minutes, then we’re onto this other thing. Treme is that way, but even more so, to the point where I respect it but I find it frustrating, in that they’ll have a life-or-death storyline that gets two minutes, and then there’ll be two minutes about Antwone and his struggles with his high school band.

Alan: It can be frustrating. I was watching an episode of Parenthood the other night that was like that. In one scene you’ve got cancer, and you’ve got post-traumatic stress disorder, and then you’ve got a teenage boy getting caught fooling around with his girlfriend. You know? It’s like, “Uh, one of these is a bit more compelling than the other.”

Matt: It can be maddening. But I respect it in the case of something like Treme, because it’s indicative of David Simon’s worldview, which I think comes out of having worked in the world of general interest daily newspapers, where you have all these different sections telling stories of varying degrees of seriousness. Even though there are certain stories that are marked as more important than others by virtue of placement on the front page, ultimately, when you hold the entire newspaper in your hand, you get a sense of all things being equal.

That’s why there’s something humbling about Treme. Rationally, we know that every one of is us but an extra in the drama of life, and so forth, even though each of us thinks we’re the lead. But David Simon’s dramas are adamant in driving that home.Welcome to Deadwood!

Matt: The Deadwood chapter of your book, more so than any other, is built around the personality of one man, David Milch, the show’s creator. Interestingly, that chapter feels like a character portrait in a book where the chapters are otherwise process-driven.

Alan: A couple of things drove that. One, I’ll admit that, in the arc of my career, Milch has been present so much that it was hard to resist putting him at the center of the Deadwood chapter. But the other is, I wanted every chapter to feel not quite like every other chapter—to find a different way into each of the shows—and Milch is his shows, and his shows are Milch, in the same way that The Sopranos is David Chase and The Wire is David Simon, but on a more elemental level, I guess.

Alan: A couple of things drove that. One, I’ll admit that, in the arc of my career, Milch has been present so much that it was hard to resist putting him at the center of the Deadwood chapter. But the other is, I wanted every chapter to feel not quite like every other chapter—to find a different way into each of the shows—and Milch is his shows, and his shows are Milch, in the same way that The Sopranos is David Chase and The Wire is David Simon, but on a more elemental level, I guess.

Matt: You and I both visited the set of Deadwood when it still existed. I really felt as if I had stepped into the mind of David Milch when I was on that set.

Alan: Yes.

Matt: Just the way they’d constructed it, so that the writers’ bungalows, and the costume place, and the stable and the props department, all of that was in the same place, and the town was a working town. The interiors and the exteriors were in the same buildings. It was like that set was actually Deadwood, the real place, except there were lights hanging from rafters in the ceilings of the rooms and cameras and cables in the streets. I can’t really think of another show that did that. Maybe Lost was that way, because they were shooting on location in Hawaii?

Alan: Not quite, because on Lost, the writers were in L.A., so that was a much more split-up thing.

I felt like a portrait of Milch was the best way to illustrate HBO in that period as a place of absolute freedom. He took advantage of that even more than Chase did, even more than Simon did. He just kind of—not “went crazy,” but kind of went to town with, “I can do all of these things, and I don’t have the checks and balances that I’ve had to deal with throughout my career. Whatever I want to do, and in whatever process that makes sense to me, that’s what I’m going to do.”

Matt: My first insight into the controlled chaos of David Milch was when I spoke to Ian McShane, aka Al Swearengen, after the Television Critics Awards ceremony in the summer of 2004, after he’d been given an award for outstanding individual achievement in drama for his performance on Deadwood. I went up to him at the bar, made some small talk, then asked, “So, what’s it like delivering those long monologues? Did your experience in legitimate theater help with that?”

Matt: My first insight into the controlled chaos of David Milch was when I spoke to Ian McShane, aka Al Swearengen, after the Television Critics Awards ceremony in the summer of 2004, after he’d been given an award for outstanding individual achievement in drama for his performance on Deadwood. I went up to him at the bar, made some small talk, then asked, “So, what’s it like delivering those long monologues? Did your experience in legitimate theater help with that?”

Then he took a drink, and he laughed.

Then he went on, “Let me tell you about Mr. Milch’s monologues. They are one or two pages long, and they are often one long sentence, if you study them, which would make them difficult to memorize and deliver anyway, simply because of that. But on top of this, Mr. Milch will never let you simply deliver a monologue. You have to be addressing a severed Indian head in a box or receiving a blowjob from a prostitute under a table.”

Alan: [Laughs]

Matt: And he goes on, “Added to which, often these monologues are rewritten up to the very last possible second, to the point where they’re handing you the pages five minutes before they call ‘action’, and the pages are still hot from the fucking printer!”

And I realized, as he was telling me this story, that McShane had absorbed the writerly rhythms of David Milch—a man who McShane speaks very highly of, by the way—even as he felt emboldened to bust the guy’s chops while talking to a journalist.

Alan: Well, that speaks to how each person who works with David Milch has to find his or her way of dealing with the controlled chaos of a David Milch production. Some people who’ve worked with Milch speak of him very highly and would work with him again in a second. Others just couldn’t handle it and wanted to get out of there as fast as possible, understandably.

Is TV better than movies?

Matt: I get the impression that maybe HBO doesn’t indulge showrunners in the way that they did during the heyday of the Davids, in the aughts.

Alan: No, I don’t think they do. I think the approach has been codified now, and the stakes are higher, and if you’re doing a show, you sort of have to propose many more things going in. I know Milch is still developing shows with HBO. But even on something like Luck, eventually [co-executive producer] Michael Mann stepped in and said, “No, you can’t do this anymore. You can’t be on the set anymore, and you have to give me scripts in advance.”

So I think there are many more rules in place, because there is a lot more money at stake. HBO, once upon a time, was the little indie film company. Now they’re more like Miramax, when Miramax started winning every Oscar ever.

Matt: It occurs to me that the rise of Miramax as a dominant force in mainstream American theatrical film came right around the same time that HBO became the dominant force in television. Not in terms of viewership, necessarily, but in terms of cultural influence. In a lot of ways, HBO was the Miramax of television, and Miramax was the HBO of mainstream theatrical cinema.

Alan: There was definitely something in the water around that time. Plus, many of the things that we think of as being ‘independent film’ are now much more mainstream. There are not a lot of genuine independent films finding their way into non-arthouse theaters anymore, either.

Matt: Over the last five years, there have been a million thinkpieces claiming that TV right now is better than movies. Even some of the people who make television have been so bold as to make that claim. What do you think about that?

Alan: When I originally thought of the concept for this book, the subtitle was going to be, “How Tony, Buffy and Stringer Made TV Better than the Movies.” Then I thought about it and realized, no—I can name so many great movies I’ve seen over the last 10 or 15 years. They weren’t the big hits. They weren’t playing on fifteen hundred screens. But they were the equivalent of a lot of the shows in this book.

Alan: When I originally thought of the concept for this book, the subtitle was going to be, “How Tony, Buffy and Stringer Made TV Better than the Movies.” Then I thought about it and realized, no—I can name so many great movies I’ve seen over the last 10 or 15 years. They weren’t the big hits. They weren’t playing on fifteen hundred screens. But they were the equivalent of a lot of the shows in this book.

I think TV has filled a role that American movies have largely given up on trying to fill, which is the middle-class drama for adults. Movie studios still do some of those, but not as many as they used to before, and the few they do are blatantly positioned as "our Oscar film of the year, which we’re going to release around Christmas.”

A White Man’s Game

Matt: You talk in the Deadwood chapter about Milch’s work on Hill Street Blues, which seems like the Big Bang from which all these other stars and planets came.

Alan: It’s the Citizen Kane of TV drama.

Matt: It probably is, and not just in the sense of being influential. There was not a single thing about Citizen Kane that had not been done somewhere else before, but the genius lay in the fact that it had never before been done all in one film, guided by one sensibility.

Alan: What [executive producers] Steven Bochco and Michael Kozoll were doing on Hill Street was lifting things from soap operas and putting them in the context of a police drama.

Matt: The open-ended, ongoing stories, the ensemble nature of it, the way the community itself was the focus.

Alan: Yes.

Matt: It’s also interesting that so many of the so-called “quality dramas,” the dramas that are descended from Hill Street and that critics think of as recappable, are extremely male in their focus. They may or may not have strong female characters built in as well, but often they’re male-focused. And more often than not they’re built around crime or violence.

Alan: True. A major difference between Treme and The Wire is that Treme doesn’t have a murder investigation every season pulling everything together. Well, there’s a little bit of that, in the scenes involving David Morse. But you might have expected them to go whole-hog on that, and they didn’t, really. Morse’s policeman is no more important on Treme than anybody else.

Alan: True. A major difference between Treme and The Wire is that Treme doesn’t have a murder investigation every season pulling everything together. Well, there’s a little bit of that, in the scenes involving David Morse. But you might have expected them to go whole-hog on that, and they didn’t, really. Morse’s policeman is no more important on Treme than anybody else.

Matt: Is there a bias within television towards male-centered stories with crime and violence?

Alan: There very clearly is. When Carolyn Strauss told me that HBO’s decision of what to do as their first show after Oz came down to The Sopranos or something by Winnie Holzman, the creator of My So-Called Life, about a female business executive at a toy company, I immediately stopped paying attention to the interview for a good five minutes, because all I was thinking about was an alternate timeline where this Winnie Holzman show was the next big HBO show. I was asking myself, would the other show have spawned imitators? Or would it not have, because “Female business executive at a toy company” is not as inherently cool as “New Jersey wiseguy in therapy”?

Matt: Maybe not as “cool,” but potentially as interesting.

Alan: Oh, I think it could have been great. But commercially—and in terms of the interests of network executives, most of whom are men—the crime shows, the antihero shows, tend to be more appealing in the abstract.

Matt: And also, let’s be honest here, there is this thing known as “escapism.” Escapism doesn’t just mean you tune in each week and get to ride the unicorn to Magicland and kill the dragon. It means you get to experience situations and emotions that maybe could happen, but that you the viewer probably could not experience in daily life. In that programming scenario that you recount, one of those proposed HBO shows clearly is more escapist than the other.

I remember reading an interview with the filmmaker Paul Schrader from about 1982. He said, and I’m paraphrasing, “To make an impact internationally, your film has to be seen by millions of people, and with some exceptions, the only kinds of films that have a chance of reaching an audience of that size are ones that have sex, violence, or both.” And that’s why so many of Schrader’s films had sex, violence, or both. It wasn’t only because those were the kinds of stories Schrader liked to tell. There were commercial considerations, too. He wanted his films to be seen and discussed. He needed eyeballs.

Alan: That totally makes sense.

I remember when you and I split the Sopranos beat at the Star-Ledger—the kinds of letters we used to get. Certainly there were people who watched the show for its Fellini-esque aspects and the other odd things Chase was doing, but there were a lot more people who were tuning in to see somebody get whacked.

Matt: And they were upset when an episode didn’t give them that.

Alan: Exactly. “What the fuck are these dreams, man? Why are we seeing Tony’s dreams?”

Matt: You see this kind of response to Breaking Bad today.

Matt: You see this kind of response to Breaking Bad today.

Alan: Yes. There are viewers who go, “Heisenberg is badass.” That’s the level at which they watch.

Matt: The negative reaction to Skyler—

Alan: Yeah, I know!

Matt: I don’t have any patience for people who insist that Skyler is a bad, boring, or unpleasant character. What she’s doing is throwing cold water on the macho fantasies of people who dig Heisenberg. Even now that she’s morally compromised, she’s still the conscience of that show, more so than any other major character.

Alan: She has unfortunately become an emblem of the misogynistic backlash that some of these shows get.

Seventies Movies, Millennial TV

Matt: Where do Lost and Battlestar Galactica fit into this era of TV drama? And Buffy the Vampire Slayer? That last one is intriguing because, correct me if I’m wrong, but if you look at the timeline, doesn’t Buffy pre-date The Sopranos?

Alan: It predates The Sopranos by two years. I think it even pre-dates Oz by something like four to six months.

Buffy was really an outlier. I had to contort myself this way and that to figure out how to include it in the book, which is so much about the effect of The Sopranos. My rationale was, it was on the air during roughly the same period, and the idea of what was happening on the WB at the time, and to a lesser extent UPN, later, in some ways paralleled what was going on at HBO, namely: Here we have an under-watched channel that wants to make a splash and is thinking, “Let’s do that by finding a creator that wants to something different. Let’s give him more rope than he’d get if he were doing this at NBC or ABC, and encourage him to do something that’s a lot more ambitious or a lot more complicated.” And again, in a genre piece.

Buffy was really an outlier. I had to contort myself this way and that to figure out how to include it in the book, which is so much about the effect of The Sopranos. My rationale was, it was on the air during roughly the same period, and the idea of what was happening on the WB at the time, and to a lesser extent UPN, later, in some ways paralleled what was going on at HBO, namely: Here we have an under-watched channel that wants to make a splash and is thinking, “Let’s do that by finding a creator that wants to something different. Let’s give him more rope than he’d get if he were doing this at NBC or ABC, and encourage him to do something that’s a lot more ambitious or a lot more complicated.” And again, in a genre piece.

Matt: When Vulture did their drama derby, the Buffy the Vampire Slayer contigent came at that contest like one of the armies in Game of Thrones.

Alan: You’re saying a sci-fi/fantasy show did really well in an Internet poll?

Matt: [Laughs] It’s different, though. The remake of Battlestar Galactica was a great and beloved show, but I don’t think it’s had anything like the staying power of Buffy. To listen to the way people talk about Buffy, you would think that it was on the air right this second!

Alan: I think that’s because a lot of people are still angry about how Battlestar ended. People may not have liked some of the later seasons of Buffy as much as the high school ones, but there’s nobody going, “Joss Whedon raped my childhood” or “He took the last seven years of my life.”

There is a kind of petulance that goes along with fandom of some of the genre shows. It’s like, “How dare you give me this thing I really, really enjoyed, until I didn’t?”

It’s important to emphasize that a lot of these shows are genre shows. The Sopranos is a mob show, but there are all these other elements. Buffy is a horror series, but that’s not all that it is. It’s a horror-action-comedy hybrid whose whole is greater than the sum of all of its different parts.

Matt: That point about being under-watched is interesting. In the late ‘90s and early aughts, when a lot of the experimentation was happening in dramas, UPN and the WB were under-watched compared to the other broadcast networks: NBC, ABC, CBS, and Fox. HBO, meanwhile, was big in the world of cable, but its viewership was also a lot smaller than that of the major broadcast networks.

In that sense, what was happening in the 90s in the minor networks and cable channels was very roughly analogous to the conditions at movie studios in the late sixties and early seventies. They desperately needed to make a splash, to matter. So much of their once built-in audience had fled to television. They were sitting there with this gigantic production apparatus, all these people under contract working on fewer and fewer films each year, these enormous sets sitting dormant a lot of the time. Things got so bad that studio bosses were willing to give up autonomy and merge with conglomerates that didn’t have anything to do with entertainment. That’s how you got Paramount hooking up with Gulf + Western and United Artists with TransAmerica.

Alan: Yeah.

Matt: And those conditions are what allowed people like Martin Scorsese and Peter Bogdanovich and Francis Coppola to slip through the door and have so much creative freedom. After a certain point, the bosses looked around, saw their kingdom in ruins, and went, “All right, we clearly don’t know what works anymore, why don’t you young guys give it a shot?”

Alan: There is very much a parallel between this era in American television and the late ‘60s and early ‘70s in American movies, with what was happening in cinema in New York and L.A.

Matt: And yet despite all these changes, vestiges of the old studio mentality remain in movies to this day, and remnants of old-fashioned broadcast network procedures remain in TV to this day. You give an example in your chapter on Lost.

Lost: What’s in the Hatch?

Matt: Lost was made by committee, basically, wasn’t it?

Alan: Yes. What happened was, Lost was conceived by Lloyd Braun, who was then the head of ABC, and who was on the verge of being fired, and needed a Hail Mary to prevent that from happening.

So he hired a writer to develop his idea, and [the script] was terrible. Then he brought in J.J. Abrams and Damon Lindelof, and Abrams quit after they made the pilot. So there were all these different cooks in there, and it’s such a strange story. A show this good shouldn’t have been made this way. And yet somehow it was.

Matt: Yeah. And you quote little things that suggest Braun was really involved in the concept, like his insistence that all the semi-magical elements on the show ultimately be revealed as being based in science fact. That’s very definitely a creative note, not like some of these notes that some executives give showrunners, along the lines of, “Well, maybe less of this or a little more of that.”

Alan: Yes, and eventually Lost did move away from that, though by that point Lloyd Braun had been long gone for a while. The people who don’t like the golden pool of light might have been happier if they’d stuck with that note!

Matt: It’s interesting that sometime around Season Three, ABC executives were telling the producers of Lost that they needed to make the show more like NBC’s Heroes, which was coming off a very successful first season, because, as we know, Heroes kind of went to hell in Season Two.

Alan: Oh, yeah, Heroes was one of those classic “Emperor’s New Clothes” situations. It was just that we were all so frustrated by what Lost was doing at the time, and then it was like, “Hey, look! Here’s this show that’s shiny and new, and it’s giving us answers right away! Everything! And clearly they’re building to something!” And it turned out they were building to somebody beating someone else up with a parking meter.

Matt: That whole thing is a testament to how incredibly ungrateful and easily distracted the heads of these major entertainment companies are. Lost, whatever problems it had in Season Two, was original, and a hit. That was ABC’s big, shiny thing. Then they looked at somebody else’s big, shiny thing that was slightly newer, and they said, “Let’s make it like that!”

Alan: And you remember all these terrible Lost imitators. Threshold and Surface and Invasion and Flash-Forward. All of them sort of took the most superficial aspects of the show and said, “Oooh, let’s do things that are weird and have mysteries and sci-fi,” and that’s not really what made Lost special.

Matt: No, it wasn’t. The industry thought [the popularity of Lost] was all about the mythology. It was partly about the mythology, but mainly it was about the same thing that makes every other really great show popular, which is that you never knew what you were going to get when you tuned in.

“Aw, they’re just making this up as they go along.”

Matt: It’s illuminating to discover in your chapters on Lost—and really, in some of the chapters on other shows, such as Breaking Bad—just how much of the plots of these shows are being driven by things that are happening behind the scenes, at the production level. Like what happened on Lost with Mr. Eko. Can you summarize that for us?

Alan: Mr. Eko, played by Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje, was one of the most popular new characters on that show, and the actor just didn’t want to live in Hawaii anymore. He said, “I want to go back to England, and please kill me off.” And then they did! And the producers told everyone that’s why they did it. And because of that, it becomes part of the whole “ah, they’re just making this up as they go along, there’s no plan” thing.

Alan: Mr. Eko, played by Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje, was one of the most popular new characters on that show, and the actor just didn’t want to live in Hawaii anymore. He said, “I want to go back to England, and please kill me off.” And then they did! And the producers told everyone that’s why they did it. And because of that, it becomes part of the whole “ah, they’re just making this up as they go along, there’s no plan” thing.

Certainly there’s an amount of improvisation in everything on television. You can’t plan for it. Nancy Marchand died in the second season of The Sopranos, and they had to deal with that.

Matt: That’s frustrating for me as a television critic, trying to communicate this to people who watch TV but don’t really know how it’s made. To say “they’re just making it up as they go” is thought of as a pejorative way to describe television, but really, it’s just a statement of fact. Every show is just making it up as they go. Mad Men, even though it had something like eighteen months off between seasons four and five, was still just making it up, in a sense. Even if they have a rough roadmap of where they want to go from episode to episode within a season—

Alan: I’m sure [Mad Men creator] Matt Weiner was responding to certain things that the actors were doing, certain things that he felt were working or not working, and that’s a form of improv.

Matt: And when you’re writing or directing anything, you might go in thinking the character is going to do “A”, but then you have an inspiration and think, “What if they do ‘B’ instead?” Maybe that’s a better idea, but once you make that decision, everything that comes after “B” has to change.

Alan: What happened in Breaking Bad, Season Three, is a classic example of that. Season Two was very meticulously plotted-out. They were working backward from the plane crash. Not everybody liked the plane crash, even though they liked Season Two as a whole. In Season Three, it was more like, “Let’s fly by the seat of our pants, and these cousins will be the big bad guys.”

Midway through the season they decided, “The cousins need to die. They’re more trouble than they’re worth. We’ll make Gus Fring the big bad.” Season Three is everyone’s favorite season of the show.

Midway through the season they decided, “The cousins need to die. They’re more trouble than they’re worth. We’ll make Gus Fring the big bad.” Season Three is everyone’s favorite season of the show.

Matt: Yes! That’s part of the appeal of television to me. I like to say that it’s not just an artistic endeavor. It’s also an athletic event.

Alan: Yes.

Matt: They have ten or 12 or 22 episodes to tell a story, and they have an outline going in, but beyond that, they have no idea where things will go. And they have to wing it.

What happened to the Russian?

Matt: If you had to pick three current shows that rank with the shows you cover in this book, what would they be?

Alan: If I had to pick shows that were as consistently good, week in and week out, the second season of Justified would slot in very comfortably with this period. The first season of Homeland would slot in very comfortably with this period. I’m a little concerned with some of the plotting that’s been going on this season; we’ll see. I’d be comfortable slotting in the first season of Game of Thrones, the second season maybe less so.

Those are three shows that, at their best, have the ability to go there. Boardwalk Empire goes there sometimes, but not consistently.

Matt: I thought it was very telling that you had this anecdote about the Russian in the “Pine Barrens” episode of The Sopranos, that Terence Winter, now the creator and executive producer of Boardwalk Empire, advocated for a scene where we would see what happened to the Russian.

Matt: I thought it was very telling that you had this anecdote about the Russian in the “Pine Barrens” episode of The Sopranos, that Terence Winter, now the creator and executive producer of Boardwalk Empire, advocated for a scene where we would see what happened to the Russian.

Alan: Yeah. Winter was always a much more traditional “beginning, middle, end" type of writer. Boardwalk Empire is a fairly traditional gangster show, whereas The Sopranos was a meditation on the state of 21st-century humanity, dressed up as a mob show.

Matt: I sometimes feel as if a meteorite hit The Sopranos, and all these chunks sprayed out and became Sons of Anarchy, Boardwalk Empire, and Mad Men. In a lot of ways, Boardwalk Empire feels like the show that those people who used to write angry letters to the Star-Ledger—

Alan: –wanted The Sopranos to be?

Matt: Exactly. “More whackin’, less yakkin’.” Mad Men is all yakkin’.

Alan: Boardwalk is definitely a more traditional drama, and is quite unapologetic about it.

You know, I forgot one other: Louie. If I were writing this book a year or two from now, there would probably be a Louie chapter in it.

You know, I forgot one other: Louie. If I were writing this book a year or two from now, there would probably be a Louie chapter in it.

Matt: And of course, technically, Louie is a comedy.

Alan: Technically.

Matt: That’s a leading comment, of course.

Alan: I know. Technically a comedy. It’s a half-hour show.

But a lot of the things we love about Louie do not, for the most part, have to do with the aspects of it that make us laugh. It’s about the worldview of it, the aesthetic choices that Louis C.K. makes as a filmmaker, and these great dramatic moments, like in the episode where he’s trying to talk his friend out of committing suicide, and the episode where he goes out on the date with Parker Posey and she sort of slowly reveals herself to be mentally ill and yet sort of exciting at the same time.

It’s got that Lost thing that you talked about, where you put it on and you have no idea what you’re gonna get.

Matt: And I can’t really think of another show – maybe certain episodes of The Sopranos, and most of Moonlighting – where you can’t be sure how literally you’re supposed to take anything that you’re seeing.

Alan: It was funny: our colleague Todd VanDerWerff mentioned the book at the AV Club, and he mentioned how David Chase said that he had read exactly one thing on the Internet about the finale of The Sopranos that understood what he was going for. The commenters immediately jumped on the idea that he must be talking about that “Masters of Sopranos” article that purported to prove that Tony died.

And I went into the comments thread and told them, “No, I asked Chase about it, he’s never read that.” And they immediately had to contort themselves. “Well, uh, maybe he has read it, but he doesn’t really know it by that name!”

Matt: I think that’s the greatest achievement of most of the shows you deal with this in this book. Because they reached a somewhat wide audience, and they had that sort of intransigent artistic quality, slowly but surely they got a popular audience accustomed to that post-‘60s European Art Cinema thing that you were alluding to earlier, that mentality that says: You don’t have to understand everything. Not everything has to be wrapped up neatly. You don’t have to like characters and find them sympathetic in order to find them interesting. And ultimately, what you take out of the experience of watching the show is the important thing.

It’s not so much what the piece of art says, exactly. It’s more about you having to chew your own food. The show is not going to chew your food for you, you know? And sometimes the meal will be indigestible, and that’s part of the experience, too.

Alan: Yeah. And that’s one of the things that’s really amazing about these shows, the fact that the experience you get out of them is not what you were expecting, and you have to work for it. When you have to work for something, the rewards are usually greater.

Alan Sepinwall has been writing about television for close to 20 years, first as an online reviewer of NYPD Blue, then as a TV critic for The Star-Ledger (Tony Soprano's hometown paper), now as author of the popular blog What's Alan Watching? on HitFix.com. Sepinwall's episode-by-episode approach to reviewing his favorite TV shows "changed the nature of television criticism," according to Slate, which called him "the acknowledged king of the form." His book The Revolution Was Televised: The Cops, Crooks, Slingers and Slayers Who Changed TV Drama Forever was published this month.

Matt Zoller Seitz is the co-founder of Press Play.

Sarah D. Bunting: It is and it isn't ambiguous. It's ambiguous about whodunnit, certainly, and has no choice in that regard; the case is unsolved, and it's not one of those "technically open" cases (op. cit. Lizzie Borden) where everyone's basically in agreement as to who did it but no charges were filed. Even the casting is ambiguous. The IMDb entry for the film lists four Zodiacs, played by three different dudes, none of whom is John Carroll Lynch’s character Arthur Lee Allen, or that creeper film archivist played by Bob Vaughn. So there's that.

Sarah D. Bunting: It is and it isn't ambiguous. It's ambiguous about whodunnit, certainly, and has no choice in that regard; the case is unsolved, and it's not one of those "technically open" cases (op. cit. Lizzie Borden) where everyone's basically in agreement as to who did it but no charges were filed. Even the casting is ambiguous. The IMDb entry for the film lists four Zodiacs, played by three different dudes, none of whom is John Carroll Lynch’s character Arthur Lee Allen, or that creeper film archivist played by Bob Vaughn. So there's that. "It's conventionally structured but unconventionally conceived and shot—a long, deliberately repetitious movie with an inconclusive ending about people whose obsession with justice bore no fruit. Its three central characters—[Detective Dave] Toschi, San Francisco Chronicle reporter Paul Avery (Robert Downey, Jr.) and editorial cartoonist Robert Graysmith believe, like all driven movie heroes, that they can succeed where others failed; obsession gives them delusions of grandeur, alienates them from their colleagues and families and leads them to the edge of madness, but never to the truth.

"It's conventionally structured but unconventionally conceived and shot—a long, deliberately repetitious movie with an inconclusive ending about people whose obsession with justice bore no fruit. Its three central characters—[Detective Dave] Toschi, San Francisco Chronicle reporter Paul Avery (Robert Downey, Jr.) and editorial cartoonist Robert Graysmith believe, like all driven movie heroes, that they can succeed where others failed; obsession gives them delusions of grandeur, alienates them from their colleagues and families and leads them to the edge of madness, but never to the truth. That's what I'd like to hear from you especially, Matt. What's happening on the surface is pretty plain: Graysmith lays out all the evidence against Allen, a victim IDs Allen, etc. How is Fincher (and/or Vanderbilt) complicating that? What are we seeing/hearing that should make us doubt the certitude of the characters?

That's what I'd like to hear from you especially, Matt. What's happening on the surface is pretty plain: Graysmith lays out all the evidence against Allen, a victim IDs Allen, etc. How is Fincher (and/or Vanderbilt) complicating that? What are we seeing/hearing that should make us doubt the certitude of the characters? I'm fascinated by movies like Zodiac — movies that adopt what seem to be very conventional approaches and then frustrate the hell out of us. Our moviegoing DNA is encoded with particular expectations, which Zodiac refuses to satisfy. We get a few inches from the finish line, but we don't go over. In some ways I think that’s more radical than if it had taken a more "art film" approach, a Blow-Up or The Conversation kind of approach.

I'm fascinated by movies like Zodiac — movies that adopt what seem to be very conventional approaches and then frustrate the hell out of us. Our moviegoing DNA is encoded with particular expectations, which Zodiac refuses to satisfy. We get a few inches from the finish line, but we don't go over. In some ways I think that’s more radical than if it had taken a more "art film" approach, a Blow-Up or The Conversation kind of approach. And then when Mageau points to another photo (again, just by way of comparing faces—saying "his face was fatter then" would have conveyed the same information and been less confusing), LeGros asks "are you changing your identification to this person?"

And then when Mageau points to another photo (again, just by way of comparing faces—saying "his face was fatter then" would have conveyed the same information and been less confusing), LeGros asks "are you changing your identification to this person?"

But isn't it always thus, even for yeggs what's been to college? Death falls on the just and the unjust alike, on big shots and little fish. No genre save horror is as comfortable with the possibility, nay, certainty, of sudden, horrendously violent extinction. Gangster pictures are populated almost exclusively by characters who've made peace with that scary reality; deep down, everyone knows life could end at any moment, but the gangster feels it more acutely, living like there's no tomorrow because as far as he knows, there isn't one. What's the threat of prison to somebody whose line of work guarantees they might get plugged, stuck, beaten to a bloody pulp or run over with a shiny new car for the sin of being on the wrong side of the law, or a turf war, or history?

But isn't it always thus, even for yeggs what's been to college? Death falls on the just and the unjust alike, on big shots and little fish. No genre save horror is as comfortable with the possibility, nay, certainty, of sudden, horrendously violent extinction. Gangster pictures are populated almost exclusively by characters who've made peace with that scary reality; deep down, everyone knows life could end at any moment, but the gangster feels it more acutely, living like there's no tomorrow because as far as he knows, there isn't one. What's the threat of prison to somebody whose line of work guarantees they might get plugged, stuck, beaten to a bloody pulp or run over with a shiny new car for the sin of being on the wrong side of the law, or a turf war, or history?

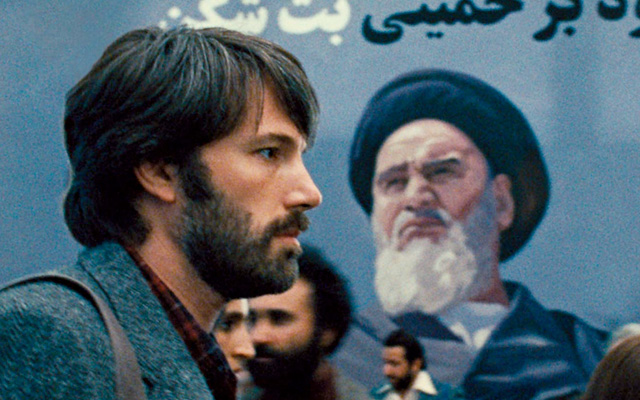

That's not the same thing as saying Argo is a masterpiece, though. Alexander Desplat's score leans on faux-Arabian Nights instrumentation and percussion, aural cliches that are frankly beneath a composer of his wit and passion. The script drops hints that the film will explore reality/fantasy, being/performing, but it never follows through. We see the hostages (including DuVall and Donovan) learning to play their parts, struggling with back stories and lines while Affleck “directs” them, but we never get a sense that the challenge affects them psychologically, beyond burdening them with homework while they’re trying to escape a nation in turmoil. Maybe this is a fair approach, but it’s disappointing because so often the situations and lines promise something deeper. The notions don't coalesce; they just hang there, like sub-narrative clotheslines on which deadpan one-liners can be affixed. And if director/star Ben Affleck and company were going to take liberties with the historical record—all movies do, don't mistake me for a historical literalist, please!—I wish they'd given the hostages and the Iranians one or two more good scenes to develop their personalities, maybe at the expense of all the "Tony Mendez loves his son" material, which, while sincere, didn't add much to the story or themes, and could have been deleted. (And why not cast a Latino actor in this part? Benicio Del Toro might've gotten a second Oscar if he'd starred in this.)

That's not the same thing as saying Argo is a masterpiece, though. Alexander Desplat's score leans on faux-Arabian Nights instrumentation and percussion, aural cliches that are frankly beneath a composer of his wit and passion. The script drops hints that the film will explore reality/fantasy, being/performing, but it never follows through. We see the hostages (including DuVall and Donovan) learning to play their parts, struggling with back stories and lines while Affleck “directs” them, but we never get a sense that the challenge affects them psychologically, beyond burdening them with homework while they’re trying to escape a nation in turmoil. Maybe this is a fair approach, but it’s disappointing because so often the situations and lines promise something deeper. The notions don't coalesce; they just hang there, like sub-narrative clotheslines on which deadpan one-liners can be affixed. And if director/star Ben Affleck and company were going to take liberties with the historical record—all movies do, don't mistake me for a historical literalist, please!—I wish they'd given the hostages and the Iranians one or two more good scenes to develop their personalities, maybe at the expense of all the "Tony Mendez loves his son" material, which, while sincere, didn't add much to the story or themes, and could have been deleted. (And why not cast a Latino actor in this part? Benicio Del Toro might've gotten a second Oscar if he'd starred in this.)

It's also a genuinely sexy film, at least at the start, before the body parts start falling off. (That closeup of the "Brundlefly Museum" of "redundant" body parts in the hero's fridge still makes me gasp; his cock is in there!) Jeff Goldblum’s Seth Brundle and Geena Davis’s Veronica “Ronnie” Quaife are one of the most real-seeming screen couples of the ‘80s. You can tell the actors were lovers during this period: they know each other's bodies as well as they know each other's senses of humor. They even share physical and vocal tics, as couples who've been together a while always do. Neither has ever looked more beautiful, but they’re attractive in a real way, not an airbrushed Hollywood way. Cronenberg treats them as real people whose wit and intelligence are as attractive as their bodies. The way Veronica plucks that bit of circuit board from Seth’s back post-coitus, and helps him clip those “weird hairs” as he's eating ice cream from a carton later; all the scenes of them eating in restaurants and walking through city marketplaces, doting on each other, exchanging the sorts of glances that only real lovers trade: these details and others make it feel as though we are observing a relationship, not a screenwriter's construct. Ditto the wonderful little character-building touches, as when Seth, who suffers from motion sickness, gets out of a taxi before it has even come to a full stop, and Ronnie gripes about a substandard cheeseburger, then eats one of the pickles first before biting into the sandwich.

It's also a genuinely sexy film, at least at the start, before the body parts start falling off. (That closeup of the "Brundlefly Museum" of "redundant" body parts in the hero's fridge still makes me gasp; his cock is in there!) Jeff Goldblum’s Seth Brundle and Geena Davis’s Veronica “Ronnie” Quaife are one of the most real-seeming screen couples of the ‘80s. You can tell the actors were lovers during this period: they know each other's bodies as well as they know each other's senses of humor. They even share physical and vocal tics, as couples who've been together a while always do. Neither has ever looked more beautiful, but they’re attractive in a real way, not an airbrushed Hollywood way. Cronenberg treats them as real people whose wit and intelligence are as attractive as their bodies. The way Veronica plucks that bit of circuit board from Seth’s back post-coitus, and helps him clip those “weird hairs” as he's eating ice cream from a carton later; all the scenes of them eating in restaurants and walking through city marketplaces, doting on each other, exchanging the sorts of glances that only real lovers trade: these details and others make it feel as though we are observing a relationship, not a screenwriter's construct. Ditto the wonderful little character-building touches, as when Seth, who suffers from motion sickness, gets out of a taxi before it has even come to a full stop, and Ronnie gripes about a substandard cheeseburger, then eats one of the pickles first before biting into the sandwich. Ronnie goes from cynical opportunism to deep and true love, but without ever losing her rationality. She looks out for herself, and not once does she seriously consider giving into Seth's, um, messianic waxing. But she never stops loving Seth. In the film’s final third, she’s wracked with guilt over finding her dream man suddenly repulsive and sad. The script is wise about how people in relationships keep feeling love and lust even when one or both are changing. When Ronnie realizes she’s pregnant with Seth’s probably-mutant baby, she decides to abort it, and it’s the correct decision; and yet when Seth crashes through the glass-bricked window of the hospital operating room to “rescue” her and their unborn larvae, she lets herself be swept into his arms anyway. It’s as if she’s in thrall to vestigial, or perhaps primordial, feminine desires to be protected and to bear a lover’s offspring. Her relapse into love is extinguished by horror once she returns to the lab and realizes what Seth has in store for her: a genetic sifting operation designed to minimize the physical presence of Brundlefly by merging him, Ronnie and the “baby.” But there’s never a sense that The Fly is copping out by trying to have things both ways—that it can’t make up its mind what it thinks of the situation. It’s fiercely true to life even though its physiological details are fiendishly unreal. Every stage of Ronnie’s emotional journey rings true. Extricating yourself from a failing relationship while pregnant is a predicament that countless women have experienced; ditto the pain of being in love with a man who’s dying and/or losing his mind, and becoming ever more frightening and repulsive, instilling his survivor with feelings of guilt and shame that she’ll never shake, only learn to manage. Mainstream movies rarely dare to depict such fraught situations in all their messy realness. The Fly does so in a science-fiction setting, with telepods and freaky prostheses and an operatic Howard Shore score that could be the music Franz Waxman heard in his head as he lay dying. It’s all quite astonishing.

Ronnie goes from cynical opportunism to deep and true love, but without ever losing her rationality. She looks out for herself, and not once does she seriously consider giving into Seth's, um, messianic waxing. But she never stops loving Seth. In the film’s final third, she’s wracked with guilt over finding her dream man suddenly repulsive and sad. The script is wise about how people in relationships keep feeling love and lust even when one or both are changing. When Ronnie realizes she’s pregnant with Seth’s probably-mutant baby, she decides to abort it, and it’s the correct decision; and yet when Seth crashes through the glass-bricked window of the hospital operating room to “rescue” her and their unborn larvae, she lets herself be swept into his arms anyway. It’s as if she’s in thrall to vestigial, or perhaps primordial, feminine desires to be protected and to bear a lover’s offspring. Her relapse into love is extinguished by horror once she returns to the lab and realizes what Seth has in store for her: a genetic sifting operation designed to minimize the physical presence of Brundlefly by merging him, Ronnie and the “baby.” But there’s never a sense that The Fly is copping out by trying to have things both ways—that it can’t make up its mind what it thinks of the situation. It’s fiercely true to life even though its physiological details are fiendishly unreal. Every stage of Ronnie’s emotional journey rings true. Extricating yourself from a failing relationship while pregnant is a predicament that countless women have experienced; ditto the pain of being in love with a man who’s dying and/or losing his mind, and becoming ever more frightening and repulsive, instilling his survivor with feelings of guilt and shame that she’ll never shake, only learn to manage. Mainstream movies rarely dare to depict such fraught situations in all their messy realness. The Fly does so in a science-fiction setting, with telepods and freaky prostheses and an operatic Howard Shore score that could be the music Franz Waxman heard in his head as he lay dying. It’s all quite astonishing.

Alan has chronicled that heady era in his new book

Alan has chronicled that heady era in his new book  Matt: Yes. But unfortunately, those people tended to end up dead.

Matt: Yes. But unfortunately, those people tended to end up dead. Alan: I talked to a lot of writers for this book, and not one of them could think of a case in which that was done before. The thinking was, “This is a show with a lot of characters and a very complex plot, people always react better to a series at the end of its run than at the beginning, let’s send the whole season out at once and see what happens.” Season Four of The Wire was the perfect season of a show to do that with, because of the whole story involving the kids. It’s probably my favorite season of the show.

Alan: I talked to a lot of writers for this book, and not one of them could think of a case in which that was done before. The thinking was, “This is a show with a lot of characters and a very complex plot, people always react better to a series at the end of its run than at the beginning, let’s send the whole season out at once and see what happens.” Season Four of The Wire was the perfect season of a show to do that with, because of the whole story involving the kids. It’s probably my favorite season of the show. Alan: I would say that Breaking Bad is a show in that vein. It took me till season three to fall in love with it in the way that I’m in love with it now, because—in much the same way as The Wire—it’s paced very slowly early on, it’s a different kind of tone than you’re used to, and you really need to see each piece built on top of every piece that came before for it to make sense, and for it to have the power that is has once you get to seasons two and three and beyond.

Alan: I would say that Breaking Bad is a show in that vein. It took me till season three to fall in love with it in the way that I’m in love with it now, because—in much the same way as The Wire—it’s paced very slowly early on, it’s a different kind of tone than you’re used to, and you really need to see each piece built on top of every piece that came before for it to make sense, and for it to have the power that is has once you get to seasons two and three and beyond. Alan: A couple of things drove that. One, I’ll admit that, in the arc of my career, Milch has been present so much that it was hard to resist putting him at the center of the Deadwood chapter. But the other is, I wanted every chapter to feel not quite like every other chapter—to find a different way into each of the shows—and Milch is his shows, and his shows are Milch, in the same way that The Sopranos is David Chase and The Wire is David Simon, but on a more elemental level, I guess.

Alan: A couple of things drove that. One, I’ll admit that, in the arc of my career, Milch has been present so much that it was hard to resist putting him at the center of the Deadwood chapter. But the other is, I wanted every chapter to feel not quite like every other chapter—to find a different way into each of the shows—and Milch is his shows, and his shows are Milch, in the same way that The Sopranos is David Chase and The Wire is David Simon, but on a more elemental level, I guess. Matt: My first insight into the controlled chaos of David Milch was when I spoke to Ian McShane, aka Al Swearengen, after the Television Critics Awards ceremony in the summer of 2004, after he’d been given an award for outstanding individual achievement in drama for his performance on Deadwood. I went up to him at the bar, made some small talk, then asked, “So, what’s it like delivering those long monologues? Did your experience in legitimate theater help with that?”

Matt: My first insight into the controlled chaos of David Milch was when I spoke to Ian McShane, aka Al Swearengen, after the Television Critics Awards ceremony in the summer of 2004, after he’d been given an award for outstanding individual achievement in drama for his performance on Deadwood. I went up to him at the bar, made some small talk, then asked, “So, what’s it like delivering those long monologues? Did your experience in legitimate theater help with that?” Alan: When I originally thought of the concept for this book, the subtitle was going to be, “How Tony, Buffy and Stringer Made TV Better than the Movies.” Then I thought about it and realized, no—I can name so many great movies I’ve seen over the last 10 or 15 years. They weren’t the big hits. They weren’t playing on fifteen hundred screens. But they were the equivalent of a lot of the shows in this book.

Alan: When I originally thought of the concept for this book, the subtitle was going to be, “How Tony, Buffy and Stringer Made TV Better than the Movies.” Then I thought about it and realized, no—I can name so many great movies I’ve seen over the last 10 or 15 years. They weren’t the big hits. They weren’t playing on fifteen hundred screens. But they were the equivalent of a lot of the shows in this book. Alan: True. A major difference between Treme and The Wire is that Treme doesn’t have a murder investigation every season pulling everything together. Well, there’s a little bit of that, in the scenes involving David Morse. But you might have expected them to go whole-hog on that, and they didn’t, really. Morse’s policeman is no more important on Treme than anybody else.

Alan: True. A major difference between Treme and The Wire is that Treme doesn’t have a murder investigation every season pulling everything together. Well, there’s a little bit of that, in the scenes involving David Morse. But you might have expected them to go whole-hog on that, and they didn’t, really. Morse’s policeman is no more important on Treme than anybody else. Matt: You see this kind of response to Breaking Bad today.

Matt: You see this kind of response to Breaking Bad today. Buffy was really an outlier. I had to contort myself this way and that to figure out how to include it in the book, which is so much about the effect of The Sopranos. My rationale was, it was on the air during roughly the same period, and the idea of what was happening on the WB at the time, and to a lesser extent UPN, later, in some ways paralleled what was going on at HBO, namely: Here we have an under-watched channel that wants to make a splash and is thinking, “Let’s do that by finding a creator that wants to something different. Let’s give him more rope than he’d get if he were doing this at NBC or ABC, and encourage him to do something that’s a lot more ambitious or a lot more complicated.” And again, in a genre piece.

Buffy was really an outlier. I had to contort myself this way and that to figure out how to include it in the book, which is so much about the effect of The Sopranos. My rationale was, it was on the air during roughly the same period, and the idea of what was happening on the WB at the time, and to a lesser extent UPN, later, in some ways paralleled what was going on at HBO, namely: Here we have an under-watched channel that wants to make a splash and is thinking, “Let’s do that by finding a creator that wants to something different. Let’s give him more rope than he’d get if he were doing this at NBC or ABC, and encourage him to do something that’s a lot more ambitious or a lot more complicated.” And again, in a genre piece.

Alan: Mr. Eko, played by Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje, was one of the most popular new characters on that show, and the actor just didn’t want to live in Hawaii anymore. He said, “I want to go back to England, and please kill me off.” And then they did! And the producers told everyone that’s why they did it. And because of that, it becomes part of the whole “ah, they’re just making this up as they go along, there’s no plan” thing.

Alan: Mr. Eko, played by Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje, was one of the most popular new characters on that show, and the actor just didn’t want to live in Hawaii anymore. He said, “I want to go back to England, and please kill me off.” And then they did! And the producers told everyone that’s why they did it. And because of that, it becomes part of the whole “ah, they’re just making this up as they go along, there’s no plan” thing. Midway through the season they decided, “The cousins need to die. They’re more trouble than they’re worth. We’ll make Gus Fring the big bad.” Season Three is everyone’s favorite season of the show.

Midway through the season they decided, “The cousins need to die. They’re more trouble than they’re worth. We’ll make Gus Fring the big bad.” Season Three is everyone’s favorite season of the show. Matt: I thought it was very telling that you had this anecdote about the Russian in the “Pine Barrens” episode of The Sopranos, that Terence Winter, now the creator and executive producer of Boardwalk Empire, advocated for a scene where we would see what happened to the Russian.

Matt: I thought it was very telling that you had this anecdote about the Russian in the “Pine Barrens” episode of The Sopranos, that Terence Winter, now the creator and executive producer of Boardwalk Empire, advocated for a scene where we would see what happened to the Russian. You know, I forgot one other: Louie. If I were writing this book a year or two from now, there would probably be a Louie chapter in it.

You know, I forgot one other: Louie. If I were writing this book a year or two from now, there would probably be a Louie chapter in it.

Tarantino has been doing this from the start of his career, from the moment in Reservoir Dogs when the doomed Mr. Brown (played by Tarantino himself) waxed profane about the supposed true meaning of Madonna’s “Like a Virgin,” then promptly died of gunshot wounds behind the wheel of a getaway car. His second film, Pulp Fiction, moves this tendency into the foreground. Nearly all of the movie’s 150-minute running time features characters talking, talking, talking, about their personalities, their values, their world views, and about other characters, some of whom we don’t get to know—or even meet—for an hour or more. All the film’s major characters are modern, workaday cousins of the Great and Powerful Oz; the film builds them up by having others repeat their (often self-created) legends until they loom in our minds like phantoms, then tears away the curtain to reveal panicked little people desperately yanking levers. “Come on,” Jules tells Vincent in the film’s opening section, “let’s get into character.”

Tarantino has been doing this from the start of his career, from the moment in Reservoir Dogs when the doomed Mr. Brown (played by Tarantino himself) waxed profane about the supposed true meaning of Madonna’s “Like a Virgin,” then promptly died of gunshot wounds behind the wheel of a getaway car. His second film, Pulp Fiction, moves this tendency into the foreground. Nearly all of the movie’s 150-minute running time features characters talking, talking, talking, about their personalities, their values, their world views, and about other characters, some of whom we don’t get to know—or even meet—for an hour or more. All the film’s major characters are modern, workaday cousins of the Great and Powerful Oz; the film builds them up by having others repeat their (often self-created) legends until they loom in our minds like phantoms, then tears away the curtain to reveal panicked little people desperately yanking levers. “Come on,” Jules tells Vincent in the film’s opening section, “let’s get into character.” Tarantino does this over and over again in Pulp Fiction. Mia Wallace is introduced as a sex goddess monitoring her date, Vincent, via surveillance cameras while mood-setting music (“Son of a Preacher Man”) thrums on the soundtrack, and then speaking to him through a microphone. Until Vincent’s car pulls into the parking lot of Jackrabbit Slims, she’s just a pair of lips and two bare feet, intriguing by virtue of her remoteness and sense of control. She seems a more strange and special person than the woman described earlier by Jules: a failed wannabe-star turned gangster’s trophy. “Some pilots get picked and become television programs,” Jules says. “Some don't, become nothing. She starred in one of the ones that became nothing.” But the date proves to be a complete disaster, as Mia mistakes Vincent’s heroin for cocaine while he’s in the bathroom and nearly dies of an overdose. And about that needle scene: Vincent and his drug dealer Lance’s terrified babbling about the right way to administer a heart injection refutes an earlier conversation in which they tried to make themselves seem like world-weary bad-asses. (Lance on his smack: “I'll take the Pepsi challenge with that Amsterdam shit, any day of the fuckin' week.” Vincent: “That’s a bold statement.”)

Tarantino does this over and over again in Pulp Fiction. Mia Wallace is introduced as a sex goddess monitoring her date, Vincent, via surveillance cameras while mood-setting music (“Son of a Preacher Man”) thrums on the soundtrack, and then speaking to him through a microphone. Until Vincent’s car pulls into the parking lot of Jackrabbit Slims, she’s just a pair of lips and two bare feet, intriguing by virtue of her remoteness and sense of control. She seems a more strange and special person than the woman described earlier by Jules: a failed wannabe-star turned gangster’s trophy. “Some pilots get picked and become television programs,” Jules says. “Some don't, become nothing. She starred in one of the ones that became nothing.” But the date proves to be a complete disaster, as Mia mistakes Vincent’s heroin for cocaine while he’s in the bathroom and nearly dies of an overdose. And about that needle scene: Vincent and his drug dealer Lance’s terrified babbling about the right way to administer a heart injection refutes an earlier conversation in which they tried to make themselves seem like world-weary bad-asses. (Lance on his smack: “I'll take the Pepsi challenge with that Amsterdam shit, any day of the fuckin' week.” Vincent: “That’s a bold statement.”) “There's this passage I got memorized,” Jules tells Pumpkin, the would-be diner robber who has dared to steal his “Bad Motherfucker” wallet. “Ezekiel 25:17. ‘The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the iniquities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men. Blessed is he who, in the name of charity and good will, shepherds the weak through the valley of darkness, for he is truly his brother's keeper and the finder of lost children. And I will strike down upon thee with great vengeance and furious anger those who attempt to poison and destroy my brothers. And you will know my name is the Lord when I lay my vengeance upon thee.’ I been saying that shit for years. And if you heard it, that meant your ass. I never gave much thought to what it meant. I just thought it was some cold-blooded shit to say to a motherfucker before I popped a cap in his ass. But I saw some shit this morning made me think twice. See, now I'm thinking, maybe it means you're the evil man, and I'm the righteous man, and Mr. 9 millimeter here, he's the shepherd protecting my righteous ass in the valley of darkness. Or it could mean you're the righteous man and I'm the shepherd, and it's the world that's evil and selfish. I'd like that. But that shit ain't the truth. The truth is, you're the weak, and I'm the tyranny of evil men. But I'm trying, Ringo. I'm trying real hard to be the shepherd.” – Matt Zoller Seitz