Warning: This piece contains aggressive and open use of spoilers. In fact, spoilers are crucial to the piece. So, if you don’t want to hear about the surprise ending, where everyone leaves on a bal–oops. Never mind.

In the late 1980s, radio commentator Ian Shoales said he didn’t like The Big Chill‘s characters because he was positive none of them would have been friends with him in high school, or words to that effect. The four friends who form the center of Drinking Buddies, though not unlikeable, give off a similar whiff of coolness—so much so, in fact, that they resemble archetypes of young, urban hipsters. This is only worthy of mention, really, because coolness, or its lack, is a defining part of the film, and where each character falls on the film’s coolness axis at any given moment in the film is inversely proportional to that character’s ability to resonate with the unassuming, unsuspecting audience member.

Two of these four confused lovers work at a microbrewery, a perfect fit for them. The microbrew has long been an acknowledged emblem of hipsterhood, regardless of how many knit-capped gals and fellas might clutch Pabst Blue Ribbon 16-ouncers in however many over-crowded performance spaces these days. The brewery provides a perfect Petri dish in which cool affectations can grow and flourish—as when Kate (Olivia Wilde) wears sunglasses at work all too frequently, perhaps to hide hangovers earned after nights spent drinking with friends, but perhaps not. Wilde is comfortable and calm in this role—it’s not a complex part, at first blush, but she uses it to occupy the screen effectively, in the best sense of the word occupy: to inhabit, to live in, to stretch out within. Her friend Luke (Jake Johnson) should be a familiar figure to anyone who’s ever eaten in a gastropub, or been to a show in a hipster deposit area such as Williamsburg, Brooklyn—he has an artfully sloppy beard, he wears a gimme-cap indoors and outdoors, he likes building bonfires (a time-honored hipster ritual), and the company he keeps (artists and other clean-cut, well-spoken types) doesn’t match his folksy exterior. He’s on roughly the same high point of the coolness axis as Kate, for most of the movie. Most of it.

Kate’s boyfriend, Chris (Ron Livingston), is at the other end of that axis, as is Luke’s girlfriend, Jill (Anna Kendrick). Chris seems to be a writer, of some kind, though it’s not clear what type. Livingston is masterful here; Chris has an ingrained arrogance about him which he tries to cover up with a rustic, outdoorsy, wholesome affect, but can’t, quite, and it’s easy to sympathize with his failure. Uncool gestures issue from him like a series of violent sneezes he is helpless to control. In one particularly poignant moment, he lends Kate a copy of Rabbit, Run, a notable misstep, given that John Updike, apart from being one of America’s great prose stylists, was a master of near-pornographic sex scenes in which female characters were almost always objects, rarely subjects. Jill, also, is a wonderfully awkward special education teacher and artist; Kendrick is miles away, in this film, from her breakout role as the malfunctioning corporate drone in Up in the Air, spending her off-hours here making dioramas. When the film requires Jill to step outside of her comfort zone, to handle the possibility that she might have done something devious, she can’t—and all we can think of is that Kate would have handled a similar challenge with far more poise and, yes, cool. We can’t be sure if this is a good thing.

So what happens to rock the apple cart? These characters drink, a lot, as a rule. When you take them out of Chicago and into the woods for a weekend retreat near a beach, well . . . what do you think’s going to happen? Boundaries are crossed: first one, and then the other, and at the end, who breaks up? Kate and her boyfriend. All in all, this isn’t surprising; Chris doesn’t have much of a chance, here, among Kate’s crowd, and he knows it, which is why, after the weekend’s events, he calls things off. What tilts the film in Kate’s favor, though, is the facial expression she makes before Chris is about to break up with her, when he says, in simple terms, that they have to talk; she mashes her lips, and she grimaces, and we know, at this moment, that she’s really feeling something, that she’s reached the antithesis of cool. When is Jill’s uncool moment? Most of the movie, perhaps, but most notably when she returns early from a tropical vacation, crying because she’s done wrong by her man, Luke, and the honest girl inside her can’t stand the thought of it. And Luke? Luke collapses when, after helping Kate move, ripping his hands up on sofa nails, and getting into a fist fight with a stranger over parking, he can’t get Kate to spend time with him alone. The gimme cap, the beard, and the down-to-earth affect help Luke very little here, and he knows he’s whipped; when she suggests they hang out with friends, he makes fun of her, but he ultimately has to leave, his mimicry coming across as empty whining more than anything else. At these moments, the film casts an anchor out, and it hits bottom; we know, after waiting patiently, that we are in the presence of humans. It’s reassuring.

Joe Swanberg, as has been duly noted elsewhere, is building a portrait of a generation with his body of work. You’ve been next to these people at the grocery store, you may have ridden on subways with them, you’ve seen them at certain movie theaters, you’ve most definitely seen them at coffee shops. It’s easy to imagine that, as Swanberg’s films expand in scope, the crisis his characters face, the crucial question—can my plaid, my organic coffee, and my iPod survive my larger life crisis?—will become a more and more resounding issue, until it’s almost deafening. This is a moving, coherent film that could communicate to viewers at any point in the coolness spectrum—the question is, how far is Swanberg willing to depart from that frame of reference to tell a story?

Max Winter is the Editor of Press Play.

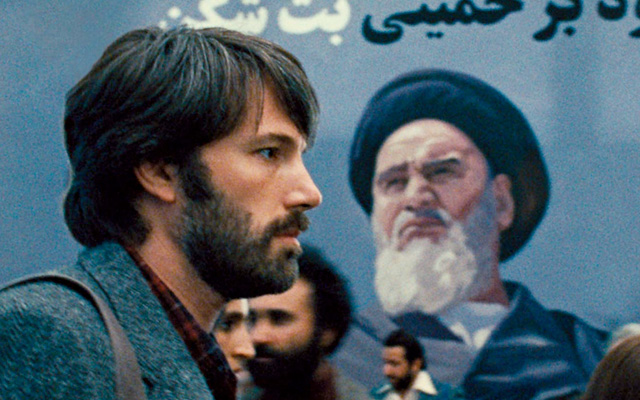

That's not the same thing as saying Argo is a masterpiece, though. Alexander Desplat's score leans on faux-Arabian Nights instrumentation and percussion, aural cliches that are frankly beneath a composer of his wit and passion. The script drops hints that the film will explore reality/fantasy, being/performing, but it never follows through. We see the hostages (including DuVall and Donovan) learning to play their parts, struggling with back stories and lines while Affleck “directs” them, but we never get a sense that the challenge affects them psychologically, beyond burdening them with homework while they’re trying to escape a nation in turmoil. Maybe this is a fair approach, but it’s disappointing because so often the situations and lines promise something deeper. The notions don't coalesce; they just hang there, like sub-narrative clotheslines on which deadpan one-liners can be affixed. And if director/star Ben Affleck and company were going to take liberties with the historical record—all movies do, don't mistake me for a historical literalist, please!—I wish they'd given the hostages and the Iranians one or two more good scenes to develop their personalities, maybe at the expense of all the "Tony Mendez loves his son" material, which, while sincere, didn't add much to the story or themes, and could have been deleted. (And why not cast a Latino actor in this part? Benicio Del Toro might've gotten a second Oscar if he'd starred in this.)

That's not the same thing as saying Argo is a masterpiece, though. Alexander Desplat's score leans on faux-Arabian Nights instrumentation and percussion, aural cliches that are frankly beneath a composer of his wit and passion. The script drops hints that the film will explore reality/fantasy, being/performing, but it never follows through. We see the hostages (including DuVall and Donovan) learning to play their parts, struggling with back stories and lines while Affleck “directs” them, but we never get a sense that the challenge affects them psychologically, beyond burdening them with homework while they’re trying to escape a nation in turmoil. Maybe this is a fair approach, but it’s disappointing because so often the situations and lines promise something deeper. The notions don't coalesce; they just hang there, like sub-narrative clotheslines on which deadpan one-liners can be affixed. And if director/star Ben Affleck and company were going to take liberties with the historical record—all movies do, don't mistake me for a historical literalist, please!—I wish they'd given the hostages and the Iranians one or two more good scenes to develop their personalities, maybe at the expense of all the "Tony Mendez loves his son" material, which, while sincere, didn't add much to the story or themes, and could have been deleted. (And why not cast a Latino actor in this part? Benicio Del Toro might've gotten a second Oscar if he'd starred in this.)

It's also a genuinely sexy film, at least at the start, before the body parts start falling off. (That closeup of the "Brundlefly Museum" of "redundant" body parts in the hero's fridge still makes me gasp; his cock is in there!) Jeff Goldblum’s Seth Brundle and Geena Davis’s Veronica “Ronnie” Quaife are one of the most real-seeming screen couples of the ‘80s. You can tell the actors were lovers during this period: they know each other's bodies as well as they know each other's senses of humor. They even share physical and vocal tics, as couples who've been together a while always do. Neither has ever looked more beautiful, but they’re attractive in a real way, not an airbrushed Hollywood way. Cronenberg treats them as real people whose wit and intelligence are as attractive as their bodies. The way Veronica plucks that bit of circuit board from Seth’s back post-coitus, and helps him clip those “weird hairs” as he's eating ice cream from a carton later; all the scenes of them eating in restaurants and walking through city marketplaces, doting on each other, exchanging the sorts of glances that only real lovers trade: these details and others make it feel as though we are observing a relationship, not a screenwriter's construct. Ditto the wonderful little character-building touches, as when Seth, who suffers from motion sickness, gets out of a taxi before it has even come to a full stop, and Ronnie gripes about a substandard cheeseburger, then eats one of the pickles first before biting into the sandwich.

It's also a genuinely sexy film, at least at the start, before the body parts start falling off. (That closeup of the "Brundlefly Museum" of "redundant" body parts in the hero's fridge still makes me gasp; his cock is in there!) Jeff Goldblum’s Seth Brundle and Geena Davis’s Veronica “Ronnie” Quaife are one of the most real-seeming screen couples of the ‘80s. You can tell the actors were lovers during this period: they know each other's bodies as well as they know each other's senses of humor. They even share physical and vocal tics, as couples who've been together a while always do. Neither has ever looked more beautiful, but they’re attractive in a real way, not an airbrushed Hollywood way. Cronenberg treats them as real people whose wit and intelligence are as attractive as their bodies. The way Veronica plucks that bit of circuit board from Seth’s back post-coitus, and helps him clip those “weird hairs” as he's eating ice cream from a carton later; all the scenes of them eating in restaurants and walking through city marketplaces, doting on each other, exchanging the sorts of glances that only real lovers trade: these details and others make it feel as though we are observing a relationship, not a screenwriter's construct. Ditto the wonderful little character-building touches, as when Seth, who suffers from motion sickness, gets out of a taxi before it has even come to a full stop, and Ronnie gripes about a substandard cheeseburger, then eats one of the pickles first before biting into the sandwich. Ronnie goes from cynical opportunism to deep and true love, but without ever losing her rationality. She looks out for herself, and not once does she seriously consider giving into Seth's, um, messianic waxing. But she never stops loving Seth. In the film’s final third, she’s wracked with guilt over finding her dream man suddenly repulsive and sad. The script is wise about how people in relationships keep feeling love and lust even when one or both are changing. When Ronnie realizes she’s pregnant with Seth’s probably-mutant baby, she decides to abort it, and it’s the correct decision; and yet when Seth crashes through the glass-bricked window of the hospital operating room to “rescue” her and their unborn larvae, she lets herself be swept into his arms anyway. It’s as if she’s in thrall to vestigial, or perhaps primordial, feminine desires to be protected and to bear a lover’s offspring. Her relapse into love is extinguished by horror once she returns to the lab and realizes what Seth has in store for her: a genetic sifting operation designed to minimize the physical presence of Brundlefly by merging him, Ronnie and the “baby.” But there’s never a sense that The Fly is copping out by trying to have things both ways—that it can’t make up its mind what it thinks of the situation. It’s fiercely true to life even though its physiological details are fiendishly unreal. Every stage of Ronnie’s emotional journey rings true. Extricating yourself from a failing relationship while pregnant is a predicament that countless women have experienced; ditto the pain of being in love with a man who’s dying and/or losing his mind, and becoming ever more frightening and repulsive, instilling his survivor with feelings of guilt and shame that she’ll never shake, only learn to manage. Mainstream movies rarely dare to depict such fraught situations in all their messy realness. The Fly does so in a science-fiction setting, with telepods and freaky prostheses and an operatic Howard Shore score that could be the music Franz Waxman heard in his head as he lay dying. It’s all quite astonishing.

Ronnie goes from cynical opportunism to deep and true love, but without ever losing her rationality. She looks out for herself, and not once does she seriously consider giving into Seth's, um, messianic waxing. But she never stops loving Seth. In the film’s final third, she’s wracked with guilt over finding her dream man suddenly repulsive and sad. The script is wise about how people in relationships keep feeling love and lust even when one or both are changing. When Ronnie realizes she’s pregnant with Seth’s probably-mutant baby, she decides to abort it, and it’s the correct decision; and yet when Seth crashes through the glass-bricked window of the hospital operating room to “rescue” her and their unborn larvae, she lets herself be swept into his arms anyway. It’s as if she’s in thrall to vestigial, or perhaps primordial, feminine desires to be protected and to bear a lover’s offspring. Her relapse into love is extinguished by horror once she returns to the lab and realizes what Seth has in store for her: a genetic sifting operation designed to minimize the physical presence of Brundlefly by merging him, Ronnie and the “baby.” But there’s never a sense that The Fly is copping out by trying to have things both ways—that it can’t make up its mind what it thinks of the situation. It’s fiercely true to life even though its physiological details are fiendishly unreal. Every stage of Ronnie’s emotional journey rings true. Extricating yourself from a failing relationship while pregnant is a predicament that countless women have experienced; ditto the pain of being in love with a man who’s dying and/or losing his mind, and becoming ever more frightening and repulsive, instilling his survivor with feelings of guilt and shame that she’ll never shake, only learn to manage. Mainstream movies rarely dare to depict such fraught situations in all their messy realness. The Fly does so in a science-fiction setting, with telepods and freaky prostheses and an operatic Howard Shore score that could be the music Franz Waxman heard in his head as he lay dying. It’s all quite astonishing.

In 1959, Elvis Presley sent Hart a postcard from Germany, where he was stationed with the 3rd Armored Division. His greeting to her was, "How are you, hot lips?" Hart told the drooling press at the time that no, they were not in love, he called her that because she had the honor of giving him his first onscreen kiss in Loving You, thereby making her the envy of swooning girls worldwide. Hart has described how nervous the two of them were filming that kissing scene. They both blushed so painfully that the makeup department was forced to do some damage-control. She was a devout Catholic and went to Mass every day at 6 A.M.. before heading to the studio. In a 2002 interview, she said that she felt fortunate to get to know Elvis when she did, that he had "an innocence" to him that was very touching. There are home movies of the two of them at her house, he playing the piano, she jamming out on a clarinet, both of them laughing and free.

In 1959, Elvis Presley sent Hart a postcard from Germany, where he was stationed with the 3rd Armored Division. His greeting to her was, "How are you, hot lips?" Hart told the drooling press at the time that no, they were not in love, he called her that because she had the honor of giving him his first onscreen kiss in Loving You, thereby making her the envy of swooning girls worldwide. Hart has described how nervous the two of them were filming that kissing scene. They both blushed so painfully that the makeup department was forced to do some damage-control. She was a devout Catholic and went to Mass every day at 6 A.M.. before heading to the studio. In a 2002 interview, she said that she felt fortunate to get to know Elvis when she did, that he had "an innocence" to him that was very touching. There are home movies of the two of them at her house, he playing the piano, she jamming out on a clarinet, both of them laughing and free.

Still, it’s important to note that Gein isn’t really a serial killer. He murdered two people, which hardly establishes his slayings as a pattern. But he is important because he became a symbol of all the Freudian motivations that we project onto killers. We make these assumptions partly because of the phallic imagery implicit in Psycho’s shower scene or Leatherface’s chainsaw in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Massacre director Tobe Hooper would make a lot of hoopla over Leatherface’s fetish in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, which plays out like a fittingly schizophrenic and limp slasher made by a big Laura Mulvey fan).

Still, it’s important to note that Gein isn’t really a serial killer. He murdered two people, which hardly establishes his slayings as a pattern. But he is important because he became a symbol of all the Freudian motivations that we project onto killers. We make these assumptions partly because of the phallic imagery implicit in Psycho’s shower scene or Leatherface’s chainsaw in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Massacre director Tobe Hooper would make a lot of hoopla over Leatherface’s fetish in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, which plays out like a fittingly schizophrenic and limp slasher made by a big Laura Mulvey fan). The funniest part about this scene is that it’s a 100% accurate description of the killer in Frenzy: he tries to rape one of his victims. But she resists and refuses to give him the satisfaction of whimpering while he breathes heavily and repeatedly growls, “Lovely!” The joke is that even McCowen’s chief, an equally impotent British man that politely hems and haws while his wife experiments with French cuisine, could guess why the real killer behaves the way he does. So while most characters in Frenzy spend the film insisting that they know exactly what the cops are looking for, McCowen inexplicably does.

The funniest part about this scene is that it’s a 100% accurate description of the killer in Frenzy: he tries to rape one of his victims. But she resists and refuses to give him the satisfaction of whimpering while he breathes heavily and repeatedly growls, “Lovely!” The joke is that even McCowen’s chief, an equally impotent British man that politely hems and haws while his wife experiments with French cuisine, could guess why the real killer behaves the way he does. So while most characters in Frenzy spend the film insisting that they know exactly what the cops are looking for, McCowen inexplicably does.