[The script for the video essay follows.]

In the opening montage to Do The Right Thing, Tina, played by Rosie Perez, dances to “Fight

The Power,” the only figure in an otherwise empty urban landscape. In this opening sequence, Tina symbolizes

everything we associate with female power: a delicate body in a kung fu pose,

her big beautiful eyes coupled with tight fists. In the world of the “strong

female character,” sex is a snarl, fingers are clenched and punches are thrown,

even though the camera zooms in and lingers on curves.

In the opening credits Tina seems active and empowered, In

the actual film, Tina is house-bound. We see moments of her talking to Mookie,

begging him to come home or lecturing him about being a man. However, we don’t

have any scenes of interiority, where Tina is established as a character, with

her own hopes and dreams.

Her existence in Do

The Right Thing is less about unpacking the world that women of color live

in than showing a sexy female figure in a poor urban landscape. After that

opening sequence, Tina is actively disempowered. Her role goes from

revolutionary to mere eye candy. Tina’s big moment in a film about individuals

making hard choices is when Mookie finally shows up and rolls an ice cube over

her segmented body.

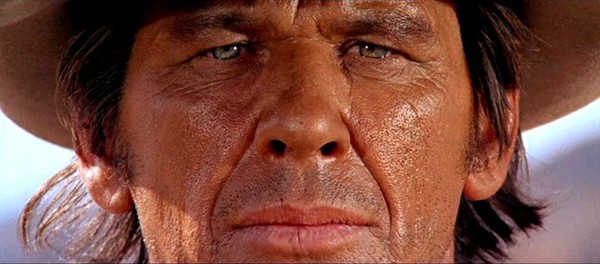

The image of the female revolutionary has often been adapted

to fit different time periods. In the 1928 film, The Passion of Joan of Arc, we see close ups of Joan’s face

crying. In a ’48 version we see Joan in full armor leading the charge, as well

as images of her bound and crying. In

the 1999 film, The Messenger, Joan’s

hair is shorn, her eyes looking intently, her lip curled into a snarl. Is Joan

of Arc’s strength from her religious conviction, or her prowess on the

battlefield?

We focus less on the substance of icons of female strength

than we do on their image. We worry about what Wonder Woman is going to wear

when she fights evil. We get concerned about whether Super Girl’s breasts look

fake. We cheer when Beyonce dresses up as Rosie The Riveter; her curled bicep

is lauded as a powerful statement about female empowerment. We care less about

what celebrities actually do to help women than whether or not they are

willing and proud to proclaim themselves feminists. We want the quick sound byte,

the 3:00 minute Upworthy video, the clever meme.

We don’t want women to be objects, but we sure as hell want

them to be symbols.

The powerful woman is defined first by how she looks and how

she holds her body. The “strong female lead” is always beautiful and fierce,

sexy and tough. She has a tragic back-story and a yearning for justice as solid

and strong as any male action hero. In today’s world, Xena, Buffy, The Bride,

and Lara Croft, as well as superheroes like Wonder Woman and Super Girl, are read

as powerful because of their physical prowess. Often their power is meant to

surprise us precisely because, despite their physical strength, they appear

pretty, delicate, and sweet.

The ubiquity of these images of female strength and power is

exacerbated in a world of Instagram images and constantly generated GIFs.

Beyonce’s allusion to Rosie the Riveter is one part homage and one part

marketing initiative. It’s a beautiful, brazen and, above all, familiar image,

a picture of feminism that we generally don’t question, an idea about power we

all agree we can get behind.

Beyonce and Janelle Monae are two artists at the forefront

of today’s feminist movement. Beyonce is deeply invested in claiming space for

female experience in a man’s world and insists on a woman’s right to “have

it all.” In contrast, Monae demands change. Monae doesn’t want us to “ban

bossy” or “lean in”, she wants us to open our minds. To embrace creativity,

queerness, sensuality.

There’s a reason Beyonce can be heralded as both a feminist

icon, and also have her lyrics used to support a mainstream film like Fifty Shades of Grey, which is less

about S&M than a relationship that meets all the criteria for abuse. In

reality, Queen Bey isn’t worried about power dynamics as long as she gets to

call the shots, which is why her rallying call of “bow down bitches!” is less a

call for female revolution than an assertion that she wants a seat in the boys

club.

Beyonce’s feminist message, though visible and important,

does not actively disrupt the mainstream. In contrast, Janelle Monae is an

R&B artist who is actually deeply invested in dismantling the way we think

about power. In her debut studio album, The

ArchAndroid, Monae plays the character Cindi Mayweather, an android who

time travels to save a civilization from forces trying to suppress freedom and

love. In her recently released Q.U.E.E.N.,

Monae also calls for revolution. She encourages solidarity amongst the

disenfranchised, the wacky and the just plain weird. Women in Monae’s videos

don’t bump and grind, objects for the camera, the way they do in almost every

single music video. They smile, they dance, they play records, they sing. While Beyonce croons slow ballads about

yearning to be an object of allure for her husband, Monae tells a male lover on

“Prime Time,” “I don’t want to be mysterious with you.”

In a world where female sexuality and power is

still often obscured, rendered strange, unintelligible, or made to exist to

fulfill a male fantasy, Monae’s insistence on being seen as a full person is

far more radical than any power pose you can copy and share on Facebook or

Instagram. While Beyonce’s brand of feminism might be a more attractive model

for consumer culture, it’s artists like Monae, who insist on questioning the

ways we are labeled, that will ultimately help us do what Tina in Do The Right Thing strives for in her

opening dance, but never ultimately achieves: get a chance to actually fight the

power.

Arielle Bernstein is

a writer living in Washington, DC. She teaches writing at American

University and also freelances. Her work has been published in The

Millions, The Rumpus, St. Petersburg Review and The Ilanot Review. She

has been listed four times as a finalist in Glimmer Train short story

contests. She is currently writing her first book.

Serena Bramble is a film editor whose

montage skills are an end result of accumulated years of movie-watching

and loving. Serena is a graduate from the Teledramatic Arts and

Technology department at Cal State Monterey Bay. In addition to editing,

she also writes on her blog Brief Encounters of the Cinematic Kind.