Throughout

his career, Paul Thomas Anderson has focused on human vulnerability. Films from

Punch Drunk Love to Magnolia to The Master to Inherent Vice to There Will Be Blood portray love as equal parts tender and strange. The

protagonists of Anderson’s films struggle with a range of

vices, from drug and sexual addiction, to anxiety and depression, to megalomania,

to gambling, to rage, to straight-up greed.

Anderson

uses vice as a way to explore different dimensions of human sadness. Each hero

is promised some kinds of greatness—Barry Egan wants to achieve success by collecting

frequent flyer miles from pudding box tops in Punch Drunk Love. Dirk Diggler hopes to keep up his fame and

recognition by virtue of his enormous package in Boogie Nights. Troubled Freddie Quell hopes to find both freedom

and family when he meets his mentor, the cult leader Lancaster Dodd, in The Master.

I was

first introduced to the world of P.T., as I affectionately called him, when I

watched Boogie Nights in a dingy

college dorm room, my sophomore year. There was a painting of an ocean on the

wall and a bottle of melatonin on the dresser, a tiny hand-me-down television

we borrowed from a friend that still played VHS tapes. At the time I spent full

days writing poems and songs and learning to be an artist and a writer. I was

smart, but I often didn’t live up to my potential and I wasn’t a particularly

good student. I have many good memories, but I have a lot of sad ones too. I

struggled throughout college with an eating disorder, I often had a strained

relationship with my parents, I rushed headfirst into a relationship that

taught me everything there is to appreciate about young love, and everything

there is to be wary of too.

In my

last year of college I’d walk past the elementary school at about noon every

day, on my way home from getting out of morning classes, and I’d see a sea of

children playing just over the horizon. My painful memories from college seem

blurry and imprecise, but images like these remain clear. At the time I didn’t

know it, but moments like these were slowly carving out my heart into the shape

it was meant to be.

Perhaps

P.T. Anderson strikes such an emotional cord in me because I discovered him at

a time when I was first learning to push back against cynicism. The truth may burn in a P.T. Anderson film, but even when it

does, we learn not to regret the scar. The

worlds that he explores are darkly sensual, hardboiled and masculine, but

softness and light always seem to linger somewhere in the periphery: sunlight

arching over an oil rig, a harmonium found next to a warehouse. We focus on tear-filled

faces throughout Magnolia, but the

final shot was still a close-up of a crying woman’s smile.–Arielle Bernstein

Arielle Bernstein is

a writer living in Washington, DC. She teaches writing at American

University and also freelances. Her work has been published in The

Millions, The Rumpus, St. Petersburg Review and The Ilanot Review. She

has been listed four times as a finalist in Glimmer Train short story

contests. She is currently writing her first book.

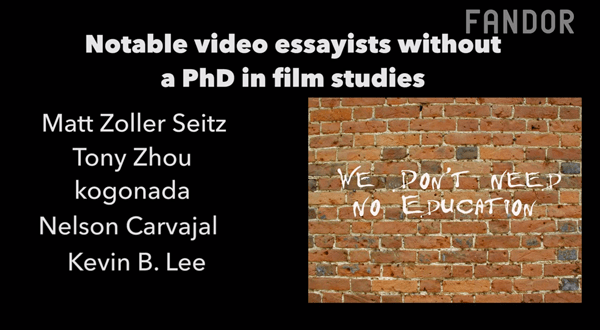

Nelson Carvajal is an independent digital filmmaker, writer and

content creator based out of Chicago, Illinois. His digital short films

usually contain appropriated content and have screened at such venues as

the London Underground Film Festival. Carvajal runs a blog called FREE CINEMA NOW which

boasts the tagline: "Liberating Independent Film And Video From A

Prehistoric Value System." You can follow Nelson on Twitter here.