EDITOR'S NOTE: Once again, Robert Nishimura's Three Reasons shines a spotlight on a film that merits the Criterion treatment.

Three Reasons: The Noisy Requiem from For Criterion Consideration on Vimeo.

By Robert Nishimura

Press Play Contributor

The Noisy Requiem revolves around Makoto Iwashita, a homeless serial killer who murders young women so that he can harvest their reproductive organs. He collects these visceral mementos so he can stuff them in the belly of his lover, the model woman of his desire, a mannequin. Makoto lives on the roof of an abandoned tenement building with his wooden mistress, making love to her through a makeshift vagina. The organs he acquires are to ensure that she can bear his child, which she eventually does until tragedy falls upon their happy home. The film follows Makoto through his daily routine: feeding some pigeons, decapitating them, finding some other chicks to murder and maim, and landing a job as a sewer scooper for a pair of incestuous midget siblings. We are also introduced to an older vagabond who carries with him a severed tree trunk that looks remarkably like a woman's torso. The rest of the film's inhabitants are the actual people who live in Shinsekai, floating in and out of the periphery like ghosts in a forgotten district of hell.

All of this happens within the first ten minutes of the film. Not a single word of dialogue has been spoken, aside from the few monosyllabic grunts here and there. Makoto practically melts into the background, a killer in plain sight, completely ignored by everyone around him. We then cut to a scene at the park, where two young schoolgirls watch some busking war veterans beg for change. One of the girls tells her friend of the dream she had the night before. In it she watches a pure white dove compete for breadcrumbs. As the bird struggles for each scrap of food, it begins to transform into a black crow, as the breadcrumbs become human remains. As the girls give the buskers some money, she explains that it was only natural for the dove to become a crow, for out of desperation to find happiness we all lose our innocence. These are some pretty profound words coming from the mouths of a couple of kids just shooting the shit in the park. But the film's director, Yoshihiko Matsui, has clearly defined where Makoto is coming from and where he will inevitably go. All the film's crows are that way out of necessity — still desperately searching for attention and love in a society that has abandoned them.

All of this happens within the first ten minutes of the film. Not a single word of dialogue has been spoken, aside from the few monosyllabic grunts here and there. Makoto practically melts into the background, a killer in plain sight, completely ignored by everyone around him. We then cut to a scene at the park, where two young schoolgirls watch some busking war veterans beg for change. One of the girls tells her friend of the dream she had the night before. In it she watches a pure white dove compete for breadcrumbs. As the bird struggles for each scrap of food, it begins to transform into a black crow, as the breadcrumbs become human remains. As the girls give the buskers some money, she explains that it was only natural for the dove to become a crow, for out of desperation to find happiness we all lose our innocence. These are some pretty profound words coming from the mouths of a couple of kids just shooting the shit in the park. But the film's director, Yoshihiko Matsui, has clearly defined where Makoto is coming from and where he will inevitably go. All the film's crows are that way out of necessity — still desperately searching for attention and love in a society that has abandoned them.

The Noisy Requiem is very much a product of Japanese cinema in the 1980s. The era marked the beginning of the end of an era that encouraged and supported innovative filmmaking, and the beginning of the next generation of underground filmmaking — one born out of necessity and circumstance.

The great radical masters of the previous decades — Nagisa Ôshima, Shôhei Imamura, Shûji Terayama, Hiroshi Teshigahara, and Kazuo Kuroki — had been assimilated and spat out by the mainstream studios, some of them producing their swan songs before fading away, unnoticed and unappreciated. The Art Theater Guild of Japan, which had fostered independent filmmakers, producing many groundbreaking films throughout the sixties and seventies, was getting out of production altogether. Only a handful of films came out of the ATG before it closed up shop in the mid-80s. But by this point the country's major studios were already flailing in a bone-dry creative pool. The majors had co-opted the themes and visual styles from underground cinema, sanitized it for mainstream audience consumption and left the masters behind; at the same time, the studios were moving towards a vertically integrated system that would force independent producers like ATG out of business.

Out of the collapse of the ATG came a new movement that favored a more DIY approach to filmmaking. Driven by Japan's growing underground punk music scene, young filmmakers took the cheapest route available: 8mm (Japan continued using single gauge 8mm film long after Super 8 was introduced in the West). Yoshihiko Matsui emerged from this tradition along with Sogo Ishii, both film students at Nihon University. Sogo Ishii would quickly gain a name for himself with the growing v-cinema boom and cyberpunk movement that took off at the start of the decade. Ishii's Panic High School and Crazy Thunder Road were all completed while the director was still in film school and are all considered required viewing by hardcore fans of the movement. Matsui Yoshihiko worked closely with Ishii during this time and acted as Assistant Director for most of Ishii's early films. In turn Ishii shot Matsui's debut feature Rusty Empty Can and his sophomore effort, the elegantly titled, Pig Chicken Suicide.

Matsui's next film was The Noisy Requiem. It wasn't completed until several years after Pig Chicken Suicide, and it took a while for a distributor to pick it up. It was not merely Matsui's finest film, but his most distinctive, an evolutionary step beyond his previous films, which owed much to the style of his partner-in-crime Ishii Sogo. Since the cyberpunk movement was gaining popularity, The Noisy Requiem became an immediate underground success, but it evaded critical attention at home and abroad. The reviews that it did get were polarized, and focused mainly on its disturbing plot points and characterizations. Its stark black-and-white, hand-held 16mm photography add to its already unnervingly naturalistic feel; there is a strong sense of immediacy to the film. Yet there is still a feeling of timelessness. At points it feels like a documentary that slips into moments of madness and sublime expressionism. Perhaps the film was ignored because of its setting in a homeless community of Kamagasaki, Shinsekai in Osaka. To this day, the Japanese government has still maintained the absurd claim that there are no homeless people in Japan, an idea that immediately falls apart if you've even been to any city in the country; a collective national urge to ignore the guy who scored a refrigerator box for the night could explain why a film like The Noisy Requiem went largely unnoticed.

As Johannes Schönherr (at Midnight Eye) already pointed out, the first ten minutes of The Noisy Requiem firmly establish Matsui's worldview and, with Shakespearean bravado, foreshadow its unavoidable outcome. From the moment our schoolgirls leave the frame the film takes a derisive turn in many stylistic directions. Makoto soon enters the scene to accost the two buskers. Matsui suddenly walks away from the action before the argument culminates into violence. Matsui's camera spastically revolves around the park, coming full circle to the action as Makoto starts beating the crap out of the handicapped veterans. Makoto represents the blackest of crows in our already pitch-black aviary. But as Matsui will soon reveal, the depths of his obscene depravity are matched only by his obsessive devotion.

As the film continues we are introduced to our two white doves: a beautiful young couple dressed in white. We never learn their names or how they ended up in Shinsekai, but we immediately recognize that they are innocent, and very much in love. Matsui overexposes the scene so that the characters are surrounded by pure white light, erasing everything else around them. They are never referenced within the film and never speak throughout their transformation, their transformation to hungry black crows, pecking at the rest of the dead. At first it seems as though this couple is meant to contrast Makoto’s black crow, but as the film progresses we witness our white dove’s fall from grace, driven by the boy’s lust for the girl. As hard as they try to maintain their innocence, their environment ultimately corrupts them. By showing the couple unable to resist temptation, Matsui only strengthens Makoto's purity in his devotion to his mannequin. His love for her is real enough, and there is no distraction from his loyalty to her.

There is no question that Makoto’s love for his mannequin is pure. We see how they first met, the moments they share together, cleaning her, tending to her, protecting her, and killing for her. This is all shown in such a way that we cannot help but empathize with Makoto. In a style usually reserved for romantic melodramas, Makoto dances with her as the camera revolves around them, with pools of filth glimmering around them in the moonlight. Later in this scene Makoto confesses his hatred for the world around him. Like Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver, Makoto is waiting for the cleansing rain to wash away the dirty streets and disgusting people he sees outside of Shinsekai. Matsui’s seems to share Makoto's view of morality in Shinsekai and of the outside world.

Matsui defends Makoto as an honorable character, but like everyone in the film, his obsession will only lead to ruin. There is no other outcome for these poor souls, and each will meet their own grisly death. Everyone is desperately clinging to whatever they can in a place that has forsaken them, and Makoto’s rooftop home offers a place for them to indulge in their passion. But saying that the characters lack any moral compass is problematic once Matsui shows how people act in “the outside world.” Matsui portrays normal society as something equally disgusting, and in some scenes he simply hides his camera and records the reactions of “normal society” to his characters. In another scene a busload of senior citizens bust out laughing when a midget woman falls over (twice). Although this scene was clearly staged, it doesn’t paint a pretty picture of a supposed moral society. Matsui doesn't condone Makoto's actions, but it is clear that Matsui considers him noble in his dedication to his mannequin.

Most recent reviews of the film are quick to call Matsui’s style nihilist and disturbing, and certainly after reading the above synopsis you would probably agree. Matsui’s guerilla filmmaking approach reinforces that kind of reading, especially since much of the film was clearly shot without permits or permission. Matsui actually set the roof of a building on fire near the film’s climax, and then snuck away to a neighboring building to film the fireman and cops sniff around the remains of Makoto’s makeshift home. Matsui’s complete disregard for linear storytelling offers a glimpse into the reality of Kamagasaki, often leaving characters behind while the camera walks up and down the street showing the real inhabitants going about their lives. Flawlessly edited, the cinematography flows effortlessly from vérité to dream-like fantasy, kinetic and visually abstract. But also slow paced, lingering on beautifully  composed moments of horror and misery, as well as love and desire. Some viewers might avoid the film because of the described violence, or others may have high expectations to see some crazy J-style weirdness. The Noisy Requiem stands apart from most genre classifications, and certainly should not be lumped together with other v-cinema cyberpunk films of that period. The violence is disturbing, but it is never graphic or fetishized. It is a deeply personal film, made with compassion for it's subject matter and an understanding of what innovative cinema can be. Like many of his mentors from the ATG, Matsui was able to evoke the spirit of his generation while maintaining his own unique vision. Having a film like The Noisy Requiem in the Criterion Collection would give Matsui the recognition he deserves, and would allow the Western world to see one of the most important independent films to come out of Japan since the fall of the Art Theatre Guild.

composed moments of horror and misery, as well as love and desire. Some viewers might avoid the film because of the described violence, or others may have high expectations to see some crazy J-style weirdness. The Noisy Requiem stands apart from most genre classifications, and certainly should not be lumped together with other v-cinema cyberpunk films of that period. The violence is disturbing, but it is never graphic or fetishized. It is a deeply personal film, made with compassion for it's subject matter and an understanding of what innovative cinema can be. Like many of his mentors from the ATG, Matsui was able to evoke the spirit of his generation while maintaining his own unique vision. Having a film like The Noisy Requiem in the Criterion Collection would give Matsui the recognition he deserves, and would allow the Western world to see one of the most important independent films to come out of Japan since the fall of the Art Theatre Guild.

Robert Nishimura is a Japan-based filmmaker, artist, and freelance designer. His designs can be found at Primolandia Productions. His non-commercial video work is at For Criterion Consideration. You can follow him on Twitter here. To watch other videos in his "Three Reasons" series, click here.

Filming in gorgeous black and white, Mario Bava was both the cinematographer and the director for Black Sunday, which has proven to be more than just a meaningless homage to the Universal visual standard. In the decades before Bava’s film, horror had become the subject of parody and pastiche. Classic monster figures suddenly had brides, reverted back to teenagers, and had mutated into radioactive amalgamations, thanks to a wave of low-budget science-y gimmicks. Bava's chiaroscuro masterpiece harkened back to a simpler time, when horror relied on tense atmospheric emotions, technical skills and claustrophobic mise-en-scene and blocking. Bava was able to accomplish this entirely on the Galatea backlot, utilizing the masters’ techniques with a distinctively innovative approach. Keeping his camera on a dolly at all times, the film moves with restless fluidity, creating an ambience unmatched in its time. When Kruvajan first arrives at Vajda Castle, the camera tracks through endless corridors and secret-passageways before leading him to Asa's tomb. It's sometimes hard to believe that Bava was able to create such a genuinely creepy atmosphere entirely on set, but his technical background elevated all the tired horror tropes to engaging new levels. Bava also found an excellent leading lady in Barbara Steele, who would later become the scream queen of Italian horror because of Black Sunday. Notoriously difficult to work with, Steele created problems for Bava in every regard. Costumes had to be changed or altered, false vampire teeth had to be remolded (then only to be removed from the film completely), and once Steele refused to come on set because she was convinced the Italians had developed a camera that could shoot through clothing. But even she remembered fondly Bava's ability as a director and as a cameraman. Somewhat shy about her status as a horror icon, she attributes her standing to Bava and what he was able to accomplish with Black Sunday.

Filming in gorgeous black and white, Mario Bava was both the cinematographer and the director for Black Sunday, which has proven to be more than just a meaningless homage to the Universal visual standard. In the decades before Bava’s film, horror had become the subject of parody and pastiche. Classic monster figures suddenly had brides, reverted back to teenagers, and had mutated into radioactive amalgamations, thanks to a wave of low-budget science-y gimmicks. Bava's chiaroscuro masterpiece harkened back to a simpler time, when horror relied on tense atmospheric emotions, technical skills and claustrophobic mise-en-scene and blocking. Bava was able to accomplish this entirely on the Galatea backlot, utilizing the masters’ techniques with a distinctively innovative approach. Keeping his camera on a dolly at all times, the film moves with restless fluidity, creating an ambience unmatched in its time. When Kruvajan first arrives at Vajda Castle, the camera tracks through endless corridors and secret-passageways before leading him to Asa's tomb. It's sometimes hard to believe that Bava was able to create such a genuinely creepy atmosphere entirely on set, but his technical background elevated all the tired horror tropes to engaging new levels. Bava also found an excellent leading lady in Barbara Steele, who would later become the scream queen of Italian horror because of Black Sunday. Notoriously difficult to work with, Steele created problems for Bava in every regard. Costumes had to be changed or altered, false vampire teeth had to be remolded (then only to be removed from the film completely), and once Steele refused to come on set because she was convinced the Italians had developed a camera that could shoot through clothing. But even she remembered fondly Bava's ability as a director and as a cameraman. Somewhat shy about her status as a horror icon, she attributes her standing to Bava and what he was able to accomplish with Black Sunday.

The man responsible for selecting this year's class is Kitano (brilliantly cast with "Beat" Takeshi Kitano), who used to work at Shiroiwa Junior High School years before becoming the mouthpiece for the BR Committee. His calm demeanor is especially off putting as he describes the rules to the game, pausing occasionally to kill a student to set an example for the rest of the class. It's especially poignant to see Takeshi Kitano in this role since it would ultimately be Fukusaku's swan song. Fukusaku had a long established career as a genre filmmaker, responsible for some of the most energetic and innovative yakuza exploitation films. His crowning achievement could be the Battles Without Honor and Humanity series, known in the West as The Yakuza Papers.

The man responsible for selecting this year's class is Kitano (brilliantly cast with "Beat" Takeshi Kitano), who used to work at Shiroiwa Junior High School years before becoming the mouthpiece for the BR Committee. His calm demeanor is especially off putting as he describes the rules to the game, pausing occasionally to kill a student to set an example for the rest of the class. It's especially poignant to see Takeshi Kitano in this role since it would ultimately be Fukusaku's swan song. Fukusaku had a long established career as a genre filmmaker, responsible for some of the most energetic and innovative yakuza exploitation films. His crowning achievement could be the Battles Without Honor and Humanity series, known in the West as The Yakuza Papers.  One notable assailant is played by Chiaki Kuriyama, who basically reprises the the same role in Quentin Tarantino's love letter to J-sploitation, Kill Bill. Fans of QT will recognize the tone that Fukusaku maintains throughout the film. Realistic violence pushed to the point of absurdity, sometimes even cartoonish. Shuya and Noriko witness all their friends (and enemies) unravel from fear and paranoia, either killing each other out of spite or suspicion. As the student body dwindles away, they form an alliance with Shogo, one of the "transfer students" who had played the game before. Together they devise a way to end the game and seek revenge on Kitano, who is surveilling them from the center of the island.

One notable assailant is played by Chiaki Kuriyama, who basically reprises the the same role in Quentin Tarantino's love letter to J-sploitation, Kill Bill. Fans of QT will recognize the tone that Fukusaku maintains throughout the film. Realistic violence pushed to the point of absurdity, sometimes even cartoonish. Shuya and Noriko witness all their friends (and enemies) unravel from fear and paranoia, either killing each other out of spite or suspicion. As the student body dwindles away, they form an alliance with Shogo, one of the "transfer students" who had played the game before. Together they devise a way to end the game and seek revenge on Kitano, who is surveilling them from the center of the island. Criterion missed their chance to nab this title, and now that The Hunger Games have begun, another company has stepped up to finally bring Battle Royale to the US. It would appear that my Three Reasons video is already an empty gesture since Anchor Bay is set to release the long-awaited special edition of Battle Royale 1 & 2 on DVD and Bluray, three days before The Hunger Games hits theaters. It's loaded with features on Fukusaku's career and the impact Battle Royale had on cinema in Japan. We can certainly trace the line from Battle Royale to The Hunger Games without too much difficulty, even though the film was never released in the US until now. Its influence on Western cinema over the past decade has justified having our own kiddy-porn death-match. The level of violence in cinema has caught up to speed that we can now have our The Hunger Games, so it seems the US is finally ready for Battle Royale. For anyone who has not seen Battle Royale, it will not disappoint, but it may steal the "edge" that The Hunger Games is so desperately trying to project.

Criterion missed their chance to nab this title, and now that The Hunger Games have begun, another company has stepped up to finally bring Battle Royale to the US. It would appear that my Three Reasons video is already an empty gesture since Anchor Bay is set to release the long-awaited special edition of Battle Royale 1 & 2 on DVD and Bluray, three days before The Hunger Games hits theaters. It's loaded with features on Fukusaku's career and the impact Battle Royale had on cinema in Japan. We can certainly trace the line from Battle Royale to The Hunger Games without too much difficulty, even though the film was never released in the US until now. Its influence on Western cinema over the past decade has justified having our own kiddy-porn death-match. The level of violence in cinema has caught up to speed that we can now have our The Hunger Games, so it seems the US is finally ready for Battle Royale. For anyone who has not seen Battle Royale, it will not disappoint, but it may steal the "edge" that The Hunger Games is so desperately trying to project.

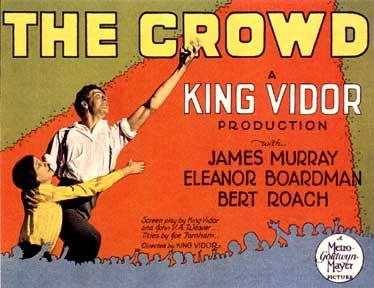

Among the films nominated for Best (Artistic) Picture at that first fabled ceremony was King Vidor's The Crowd. Considered by many to be his masterpiece and a timeless American classic, The Crowd shares many thematic elements to this years Best Picture winner, Michel Hazanavicus' The Artist. Although both film's protagonists have similar trajectories, The Crowd is the opposite of how The Artist presents itself. King Vidor's film was remarkably different for its time in portraying a very non-Hollywood representation of everyday life. While revealing the stylistic influence of his European predecessors, Vidor evoked a natural realism that had not been seen before on American screens. Casting a relatively unknown actor (James Murray) in the lead role of John Sims, he embodied the everyday struggle of a typically average American trying his best to make his mark in a massively foreboding big city. An ambitious, experimental, and socially relevant film, its no wonder why it had been nominated for Best Picture, or why it still resonates today.

Among the films nominated for Best (Artistic) Picture at that first fabled ceremony was King Vidor's The Crowd. Considered by many to be his masterpiece and a timeless American classic, The Crowd shares many thematic elements to this years Best Picture winner, Michel Hazanavicus' The Artist. Although both film's protagonists have similar trajectories, The Crowd is the opposite of how The Artist presents itself. King Vidor's film was remarkably different for its time in portraying a very non-Hollywood representation of everyday life. While revealing the stylistic influence of his European predecessors, Vidor evoked a natural realism that had not been seen before on American screens. Casting a relatively unknown actor (James Murray) in the lead role of John Sims, he embodied the everyday struggle of a typically average American trying his best to make his mark in a massively foreboding big city. An ambitious, experimental, and socially relevant film, its no wonder why it had been nominated for Best Picture, or why it still resonates today.

The most important component that entices the cult film fan is the film's relative obscurity – the exclusivity that comes from finding a rare cinematic gem, being a part of the privileged few who know about it, obsess over it, and quote from it incessantly. Prime examples for cultist celebration are films that had a limited run or never saw a proper release. Usually this was due to poor initial reviews or controversy involving the production or subject matter. The most popular examples of the cult film are those which, by mainstream standards, are "bad" movies. The argument that "it's so bad, it's good" is one that allows fans to have an ironic distance from the films, and is the major pitfall in the cultist ethos. The pinnacle of this would be the riffing maestros who ran Mystery Science Theatre 3000, their constant comedic commentary even overshadowing a few "good" movies. Another unfortunate aspect of the cult film is that once a film is given that status, it rarely, if at all, is allowed to transcend that distinction. The kitsch label is impossible to shake.

The most important component that entices the cult film fan is the film's relative obscurity – the exclusivity that comes from finding a rare cinematic gem, being a part of the privileged few who know about it, obsess over it, and quote from it incessantly. Prime examples for cultist celebration are films that had a limited run or never saw a proper release. Usually this was due to poor initial reviews or controversy involving the production or subject matter. The most popular examples of the cult film are those which, by mainstream standards, are "bad" movies. The argument that "it's so bad, it's good" is one that allows fans to have an ironic distance from the films, and is the major pitfall in the cultist ethos. The pinnacle of this would be the riffing maestros who ran Mystery Science Theatre 3000, their constant comedic commentary even overshadowing a few "good" movies. Another unfortunate aspect of the cult film is that once a film is given that status, it rarely, if at all, is allowed to transcend that distinction. The kitsch label is impossible to shake. Robert Blake gives an amazingly humane performance as John Wintergreen, an Arizona motorcycle cop whose moral code is so steadfast that it stands in opposition to both the left and the right. Wintergreen ritualizes his preparation for work, donning his uniform, determined to uphold the letter of the law in the protection of the innocent. Wintergreen only wants to get away from "the white elephant" they make him ride and become a detective, where he would be paid to think and not merely pass out speeding tickets. When he stumbles upon an apparent suicide in this sleepy little town, only Wintergreen can recognize it as a homicide, and is finally given an opportunity to show his skills as a detective. Under the inept tutelage of a senior detective, Wintergreen quickly realizes that corruption and ignorance is beset on both sides of the law. The opposing forces of the right and left leave Wintergreen little space to stand his own ground as a humanist.

Robert Blake gives an amazingly humane performance as John Wintergreen, an Arizona motorcycle cop whose moral code is so steadfast that it stands in opposition to both the left and the right. Wintergreen ritualizes his preparation for work, donning his uniform, determined to uphold the letter of the law in the protection of the innocent. Wintergreen only wants to get away from "the white elephant" they make him ride and become a detective, where he would be paid to think and not merely pass out speeding tickets. When he stumbles upon an apparent suicide in this sleepy little town, only Wintergreen can recognize it as a homicide, and is finally given an opportunity to show his skills as a detective. Under the inept tutelage of a senior detective, Wintergreen quickly realizes that corruption and ignorance is beset on both sides of the law. The opposing forces of the right and left leave Wintergreen little space to stand his own ground as a humanist. Just as its politics were easily misconstrued, Electra Glide in Blue takes on various styles which makes it difficult to define. Rarely do we find a more confident directorial debut that runs the gamut from experimentalism to classic traditionalism. James William Guercio began his career as the producer of The Chicago Transit Authority (better known as just Chicago), and his roots in music production shine through. The film has elements of a concert film and frequent moments of musical montage. On the surface it seems like a typical murder mystery, but as in its Easy Rider counterpart, the plot has little consequence on how the story unfolds. Guercio was set to make a modern western parable and hired veteran cinematographer

Just as its politics were easily misconstrued, Electra Glide in Blue takes on various styles which makes it difficult to define. Rarely do we find a more confident directorial debut that runs the gamut from experimentalism to classic traditionalism. James William Guercio began his career as the producer of The Chicago Transit Authority (better known as just Chicago), and his roots in music production shine through. The film has elements of a concert film and frequent moments of musical montage. On the surface it seems like a typical murder mystery, but as in its Easy Rider counterpart, the plot has little consequence on how the story unfolds. Guercio was set to make a modern western parable and hired veteran cinematographer

All of this happens within the first ten minutes of the film. Not a single word of dialogue has been spoken, aside from the few monosyllabic grunts here and there. Makoto practically melts into the background, a killer in plain sight, completely ignored by everyone around him. We then cut to a scene at the park, where two young schoolgirls watch some busking war veterans beg for change. One of the girls tells her friend of the dream she had the night before. In it she watches a pure white dove compete for breadcrumbs. As the bird struggles for each scrap of food, it begins to transform into a black crow, as the breadcrumbs become human remains. As the girls give the buskers some money, she explains that it was only natural for the dove to become a crow, for out of desperation to find happiness we all lose our innocence. These are some pretty profound words coming from the mouths of a couple of kids just shooting the shit in the park. But the film's director, Yoshihiko Matsui, has clearly defined where Makoto is coming from and where he will inevitably go. All the film's crows are that way out of necessity — still desperately searching for attention and love in a society that has abandoned them.

All of this happens within the first ten minutes of the film. Not a single word of dialogue has been spoken, aside from the few monosyllabic grunts here and there. Makoto practically melts into the background, a killer in plain sight, completely ignored by everyone around him. We then cut to a scene at the park, where two young schoolgirls watch some busking war veterans beg for change. One of the girls tells her friend of the dream she had the night before. In it she watches a pure white dove compete for breadcrumbs. As the bird struggles for each scrap of food, it begins to transform into a black crow, as the breadcrumbs become human remains. As the girls give the buskers some money, she explains that it was only natural for the dove to become a crow, for out of desperation to find happiness we all lose our innocence. These are some pretty profound words coming from the mouths of a couple of kids just shooting the shit in the park. But the film's director, Yoshihiko Matsui, has clearly defined where Makoto is coming from and where he will inevitably go. All the film's crows are that way out of necessity — still desperately searching for attention and love in a society that has abandoned them.

composed moments of horror and misery, as well as love and desire. Some viewers might avoid the film because of the described violence, or others may have high expectations to see some crazy J-style weirdness. The Noisy Requiem stands apart from most genre classifications, and certainly should not be lumped together with other v-cinema cyberpunk films of that period. The violence is disturbing, but it is never graphic or fetishized. It is a deeply personal film, made with compassion for it's subject matter and an understanding of what innovative cinema can be. Like many of his mentors from the ATG, Matsui was able to evoke the spirit of his generation while maintaining his own unique vision. Having a film like The Noisy Requiem in the Criterion Collection would give Matsui the recognition he deserves, and would allow the Western world to see one of the most important independent films to come out of Japan since the fall of the Art Theatre Guild.

composed moments of horror and misery, as well as love and desire. Some viewers might avoid the film because of the described violence, or others may have high expectations to see some crazy J-style weirdness. The Noisy Requiem stands apart from most genre classifications, and certainly should not be lumped together with other v-cinema cyberpunk films of that period. The violence is disturbing, but it is never graphic or fetishized. It is a deeply personal film, made with compassion for it's subject matter and an understanding of what innovative cinema can be. Like many of his mentors from the ATG, Matsui was able to evoke the spirit of his generation while maintaining his own unique vision. Having a film like The Noisy Requiem in the Criterion Collection would give Matsui the recognition he deserves, and would allow the Western world to see one of the most important independent films to come out of Japan since the fall of the Art Theatre Guild.

and as significant as the invention of drama or the novel,” Mead said of the PBS series, “…a new way in which people can learn to look at life, by seeing the real life of others interpreted by the camera.” But although Brooks engages the PBS series head-on, he soon moves past it, into outrageous, prescient comedy. The hairstyles, clothes, technology and architecture are dated, but in every other way, Real Life feels like it came out last week.

and as significant as the invention of drama or the novel,” Mead said of the PBS series, “…a new way in which people can learn to look at life, by seeing the real life of others interpreted by the camera.” But although Brooks engages the PBS series head-on, he soon moves past it, into outrageous, prescient comedy. The hairstyles, clothes, technology and architecture are dated, but in every other way, Real Life feels like it came out last week. In Real Life, an ambitious young filmmaker (Brooks, playing "himself") goes to Phoenix and dogs the middle-class Yeager family (headed by

In Real Life, an ambitious young filmmaker (Brooks, playing "himself") goes to Phoenix and dogs the middle-class Yeager family (headed by  The biting script — which was co-written by

The biting script — which was co-written by

The Devils was partly based on

The Devils was partly based on  A quick search will reveal just what exactly had to be removed, and there's little point in including those scenes here (or in the video) because it has become irrelevant. Like censoring a porno to exclude the money shot, Russell's worldview is loud and clear; we just don't get the satisfaction at the end. Cross-dressing kings shooting Protestants dressed like birds, a nunnery home for wayward nymphomaniacs, barbaric 17th-century medical practices, torture, rape and religious genocide – just some of the family-friendly fun actually deemed "good enough" to make the cut. Maybe if critics had viewed the film as satire, or at least (charred-) black comedy, the scenes they singled out would be unnecessary to excise. Russell so willingly made the cuts because his overall message had remained intact and, luckily, overlooked by the censors.

A quick search will reveal just what exactly had to be removed, and there's little point in including those scenes here (or in the video) because it has become irrelevant. Like censoring a porno to exclude the money shot, Russell's worldview is loud and clear; we just don't get the satisfaction at the end. Cross-dressing kings shooting Protestants dressed like birds, a nunnery home for wayward nymphomaniacs, barbaric 17th-century medical practices, torture, rape and religious genocide – just some of the family-friendly fun actually deemed "good enough" to make the cut. Maybe if critics had viewed the film as satire, or at least (charred-) black comedy, the scenes they singled out would be unnecessary to excise. Russell so willingly made the cuts because his overall message had remained intact and, luckily, overlooked by the censors. What makes the film so compelling is

What makes the film so compelling is