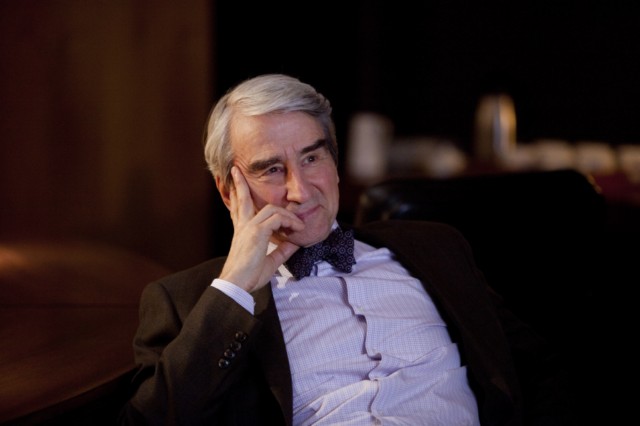

One of the reasons I wish The Newsroom spent more time following its characters as they report stories is that there’s a thesis floating through the show about what happens when people apply the methods they use in journalism to their personal lives. Jim is honest and straight-forward but doesn’t promote himself enough, Maggie is passionate when she has an idea but not always very clear about what he wants, MacKenzie is constantly on the brink of hysteria, and Neal is enthusiastic about everything, be it Bigfoot or his dishy girlfriend. The one person we see doing both a lot of dating and a lot of news work is Will. And as he starts dating with intentions other than irritating MacKenzie in this week’s episode, he can’t shake his on-air persona, and the results prove, if not disastrous, the waste of some delicious-looking drinks.

It turns out that a mission to civilize may work for long-term viewers who only have to deal with you for an hour a night—as you’d think any of the women in his office could have warned Will (even though Sloan tells us herself that she’s a social incompetent). But it’s much less effective when it sounds like you’re patronizing to a woman you don’t even know. First, Will tells a gossip columnist in the middle of a New Year’s Eve party, “You can be part of the change! You don’t have to go back to writing gossip!”—which underscores the fact that, as she’s clearly explained to him, she’s happy with her job and has no particular moral qualms about doing it.

It turns out that a mission to civilize may work for long-term viewers who only have to deal with you for an hour a night—as you’d think any of the women in his office could have warned Will (even though Sloan tells us herself that she’s a social incompetent). But it’s much less effective when it sounds like you’re patronizing to a woman you don’t even know. First, Will tells a gossip columnist in the middle of a New Year’s Eve party, “You can be part of the change! You don’t have to go back to writing gossip!”—which underscores the fact that, as she’s clearly explained to him, she’s happy with her job and has no particular moral qualms about doing it.

Later, he gets his picture on the cover of a gossip magazine, bumping Jennifer Aniston, because he can’t stop himself from lecturing another date—Kathryn Hahn, who HBO should consider making the star of her own show rather than a vehicle for lessons taught to characters like Will and Girls’ Jessa—on what would happen to her if she pulled a gun on an attacker. Will ends up pointing her own unloaded pistol at her, looking like a jerk in the moment, and in the papers.

Finally, he tells another date that she’s a bad person for enjoying the reality shows the gossip columnist covers, because the “chocolate souffle on this menu is a guilty pleasure. The Archies singing ‘Sugar, Sugar’ is a guilty pleasure. Human cockfighting makes us mean and desensitizes us.” When she asks if he thinks she’s a mean person, he tells her, “Yes, but thank goodness you met me in time!” Throwing drinks in people’s faces seems to be the way powerful women express their displeasure on television these days in shows from The Newsroom to Smash, but Will’s dates are among the most justified libation-flingers anywhere on the small screen.

That’s not to say there isn’t some real pathos here. It’s sad to watch Will joust with Wade and MacKenzie in his office only to go quiet outside it. “Do people really just walk up to people?” Will asks Sloan. “I’ve seen it on TV,” she tells him. Later, when Charlie lectures him on his emotional life, Will lashes out at his boss as a peddler of fantasy. “It doesn’t work like in the movies,” he says, wounded. “It doesn’t work at all.”

The Newsroom might have less gender trouble if it directly and consistently explored the ways in which traits and behaviors that help men succeed in business end up limiting their abilities to have successful, reciprocal relationships with women. But doesn’t go there this time, portraying Will’s dates as a series of shallow shrews and crazy broads, acting as tools of the devious and mostly off-screen Leona, who retaliate unfairly when they toss cocktails at him or land him in the gossip column. The show may think Will is bad at expressing himself, but it doesn’t really bother to question the arrogance of his mission to civilize. This episode is, after all, called “I’ll Try to Fix You.”

But the show does one smart thing: it makes Will’s inability to get over the end of his relationship with MacKenzie look foolish, and it has him suffer real consequences for clinging to his resentment. It turns out that when he renegotiated his contract so he could fire MacKenzie at will, he took a non-compete clause in trade. “How much do you hate me?” MacKenzie asks him, shocked at Will’s stupidity and pettiness, the fact that he’s willing to risk ending his own career in order to retain the ability to threaten and intimidate her. It was one of the first moments when I felt like The Newsroom and I see Will the same way, as an angry man whose superiority complex carries with it the power to harm himself and other people.

And it’s a relief that unlike in the pilot, where Will and MacKenzie argue about their relationship and philosophies of news, oblivious to the fact that their employees are reporting the Deepwater Horizon explosion, the two of them stop this argument (even though I hope they revisit it) to start covering the shooting of Gabrielle Giffords. Once again, though, it’s a story about how Will and the News Night team get the story right.

But in a slight improvement from the show’s dominant newsgathering tactic, they don’t score because they have secret knowledge from being related to sources, or living with them, or hiding under their beds, or as is the case at the beginning of the episode (when MacKenzie’s boyfriend Wade tips Will to a hot story about the underfunding of the fight against financial fraud), because they’re dating. The show clearly hasn’t abandoned the idea that that’s how reporters get information: when Will complains that “I’ve got a staff of paid professionals” doing reporting so he doesn’t have to talk to MacKenzie’s squeeze, she tells him that his employees are “mostly using inside sources like Wade.”

This incident is one of the few times we’ve actually seen the process of deciding what to put on air dramatized and given more than a few seconds of screen time, as is clear in Reese's confrontation with Will during a commercial break:

And at least the team makes the right judgment call because of the principles guiding their work. And as the World’s Biggest Don Fan, it’s gratifying that the show’s writers, after spending so much time beating up on him as a weak-willed sellout, let him be the one to tell Will, “It’s a person. A doctor pronounces her dead, not the news.”

The celebration that follows is a little over the top—not making an error isn’t the same thing as advancing a story or getting an exclusive. But it’s the loosest we’ve seen these characters, given that they’re normally composed to the point of rigidity. And I was totally with Will when he declared, “You’re a fucking newsman, Don. I ever tell you otherwise, you punch me in the face,” both because it recognized Don’s integrity, and because it made Will feel like a real journalist. One of the stranger things about the show is that its self-congratulation is so pure: there’s no trash talk, no visceral distaste for News Night’s rivals, none of the slightly creepy but inevitable celebration of scoops in a way that reduces human experience to a victory or defeat. I don’t know if this was intentional or not, but I appreciated the venality of the moment. Will and the team are so wrapped up in their own sense of righteousness that they forget the Congresswoman who may be dying, the civilians who are already dead. The Newsroom would be more fun as a show that actually weighs Will’s flaws and virtues without tipping the scales in his favor, that questions whether what the news needs to stand against the suits is not saints, but jerks.

Alyssa Rosenberg is a culture reporter for ThinkProgress.org. She is a correspondent for TheAtlantic.com and The Loop 21. Alyssa grew up in Massachusetts and holds a BA in humanities from Yale University. Before joining ThinkProgress, she was editor of Washingtonian.com and a staff correspondent at Government Executive. Her work has appeared in Esquire.com, The Daily, The American Prospect, The New Republic, National Journal, and The Daily Beast.

But in the drug game, being "the man" is like having a target on your back, and Walt will realize soon enough that his problems have most likely been more augmented by Fring's murder than solved by it. In fact, below, in a callback to Season Two's predictive pre-credit scenes, we see a Walt with a full head of hair distractedly chit-chatting with a Denny's waitress, while nervously checking over his shoulder every few seconds. Breaking Bad’s signature sense of dread is almost overbearing (just watching the scene made me feel like I was about to have a panic attack), and as soon as we see that Walt is actually there to meet Lawson (his black market dealer for all things sidearm-related, played perfectly with cautious resignation ["Good luck, I guess."] by Deadwood's Jim Beaver), we know things can't be going as swimmingly as Walt thought they would when he said, "I won." When Walt uncovers the M60 machine gun Lawson has dropped off for him, it's obvious that something has gone severely pear-shaped.

But in the drug game, being "the man" is like having a target on your back, and Walt will realize soon enough that his problems have most likely been more augmented by Fring's murder than solved by it. In fact, below, in a callback to Season Two's predictive pre-credit scenes, we see a Walt with a full head of hair distractedly chit-chatting with a Denny's waitress, while nervously checking over his shoulder every few seconds. Breaking Bad’s signature sense of dread is almost overbearing (just watching the scene made me feel like I was about to have a panic attack), and as soon as we see that Walt is actually there to meet Lawson (his black market dealer for all things sidearm-related, played perfectly with cautious resignation ["Good luck, I guess."] by Deadwood's Jim Beaver), we know things can't be going as swimmingly as Walt thought they would when he said, "I won." When Walt uncovers the M60 machine gun Lawson has dropped off for him, it's obvious that something has gone severely pear-shaped.

This is the flip side of the revelation from last week: if the law is insufficient to provide justice, people desperate for justice will go outside the law. Nobody in the episode questions whether Crawley was a murderer. In fact, there’s not even a significant argument as to whether Crawley committed the murder he went to prison for, or whether he deserved to die for it. But there was a crime, and Walt and the rest of his office are investigating.

This is the flip side of the revelation from last week: if the law is insufficient to provide justice, people desperate for justice will go outside the law. Nobody in the episode questions whether Crawley was a murderer. In fact, there’s not even a significant argument as to whether Crawley committed the murder he went to prison for, or whether he deserved to die for it. But there was a crime, and Walt and the rest of his office are investigating.

And newbie vamp Tara (Rutina Wesley) not only owning a surrogate mom in her maker Pam but a new BFF in Jessica (Deborah Ann Woll) courtesy an adorable scene—which you can watch above—where the latter waxes irresistable about sex, blood, morality, and how tough it is being a vamp, alone. Yes, there's a tiff over rights to Hoyt's neck, but for reals, these girls are made for each other: we just wonder how much . . .

And newbie vamp Tara (Rutina Wesley) not only owning a surrogate mom in her maker Pam but a new BFF in Jessica (Deborah Ann Woll) courtesy an adorable scene—which you can watch above—where the latter waxes irresistable about sex, blood, morality, and how tough it is being a vamp, alone. Yes, there's a tiff over rights to Hoyt's neck, but for reals, these girls are made for each other: we just wonder how much . . .