VIDEO ESSAY: Steadicam Progress – the Career of Paul Thomas Anderson in Five Shots

With The Master winning the Best Cinematography award from the National Society of Film Critics over the weekend, here's a look at the evolution of Paul Thomas Anderson's approach to his films' camerawork over his first five features. The video above and essay posted below originally appeared in Sight & Sound.

One thing I wish I had explored in some way was the contribution of Anderson's longtime cinematographer Robert Elswit, who shot Anderson's first five features. The video makes the implicit auteurist assumption that the visions being expressed through the camerawork are that of the director, with the cinematographer acting as a technical facilitator. This of course is a gross oversimplifcation of the collaborative dynamic between director and cinematographer that perhaps gives too much credit to one party.

My dissatisfaction with this reductive approach informs the topic of my subsequent video essay for Sight & Sound, an exploration of the creative contribution of special effects team Rhythm & Hues, as a postulation of the artistic visions brought about by technical craftsmanship.

—–

Thinking on what sets The Master apart from Paul Thomas Anderson’s earlier films, what strikes me most vividly is a marked difference in camera movement and staging. I wouldn’t be surprised if a proper cinemetric analysis found that up to half of the film’s running time consists of close-ups with little to no camera movement.

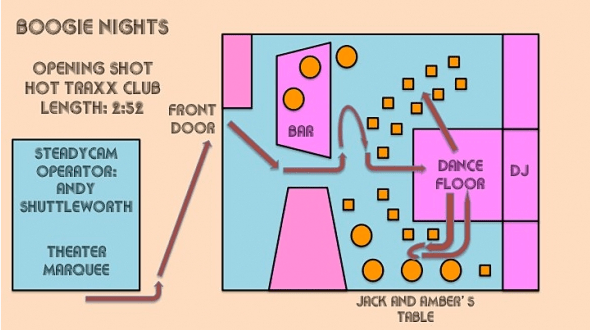

This is a far cry from the run-and-gun days of Boogie Nights and Magnolia with their stunning array of sweeping Steadicam shots, push-ins and whip pans. But upon surveying his career film by film, one can trace an evolution in his technique. This video essay examines one signature tracking shot from each of Anderson’s five previous features, showing how each epitomises his cinematography at each point, from the flashiness of his earlier films to a more subtle approach that favours composition over movement.

While The Master offers a couple of swirling tracking shots in a department store, and later a pair of straight-line lateral tracking shots to match the onanistic thrill of motorcycle joyriding, the film settles more often into shot/reverse shot dialogues in cozy interior sets. It seems that Anderson’s camera strategy here has less in common with Scorsese, Altman or even Kubrick (with all of whom he’s frequently compared) than with Jonathan Demme. Indeed, in the DVD commentary of Boogie Nights, Anderson expresses a profound emulation of Demme, though Demme himself couldn’t recognise a shot from Boogie Nights that Anderson claimed to have blatantly derived from him.

Here the connection is apparent as never before, in a film that seems less concerned with riding the kinetic thrill of a camera set in motion than in tapping the psychic voltage of physiognomies seen up close. In his most psychologically intimate film to date, Anderson largely foregoes his signature camera movements in order to tunnel into the human mind.

Kevin Lee is a film critic, filmmaker, and leading proponent of video form film criticism, having produced over 100 short video essays on cinema and television over the past five years. He is a video essayist and founding editor of Fandor, and editor of Indiewire’s Press Play blog, labelled by Roger Ebert as “the best source of video essays online.” He tweets at @alsolikelife.