I grew

I grew

up with thin white girl icons—with angry girl rockers like Fiona Apple crawling

half naked and hungry all over the floor, and Poe’s deep sultry voice, shifting

from ethereal to mad, everything about her skinny-armed longing. The feminist

rockers when I was a teen wilted and cried and clawed and spit. In the late 90s

a loud voice was always about rage, and female artists often sold a seemingly

contradictory image—a strong heart and fragile body.

My

mother, who emigrated from Cuba to America in the late sixties, could never

understand my obsession with thinness as a teenager. She drank water with heaps

of sugar in it to try and put on weight—curviness was seen as a sign of

sensuality, of sexiness. Certainly, there were curvier icons I could have looked

up to. The waif craze was in many ways a reaction to the aerobics-inspired look

of the 80s, with super models like Cindy Crawford and Naomi Campbell and pop

sensations like Madonna ushering in an era of sexuality that was large-bosomed

and muscular. And throughout the 90s, pop stars from J-Lo to Beyonce were famous

for their impeccable curves.

The waif

look appealed to me because it seemed defiant and dangerous. In reality it just

offered a different type of body as a fashion accessory.

To my mother,

my preference for thinness was more than a trend; it represented a kind of

cultural abandonment, a desire to be perceived as WASP-y and white, rather than

who I really was: a daughter of immigrants, a Latin American Jew. Two specific

markers of American assimilation—my thinness and blond hair, coupled with my

not having an accent, seemed to grant me access to things my mother never felt

she had access to.

But I

never felt as though I had complete access either, even if on the surface I

seemed to have it. I always felt like an imposter, as if I was wearing a mask I

could never take off.

We are all reduced to

our body parts.

The past several months

have been particularly depressing for anyone with a female body. Headlines

describing rape and sexual assault are virtually everywhere, from the numerous women speaking out against Bill Cosby, to the attention placed on

college campuses and how they could be doing more to prevent rape and sexual

assault.

In his essay on the rape

allegations against Cosby, Ta-Nehisi Coates reflects on the horrors of rape,

saying, “Rape

constitutes the loss of your body, which is all you are, to someone else.”

Likewise, in a recent essay, Roxane Gay considers the language of a sexual

assault from a Rolling Stone article that chronicles the experiences of a UVA

student who describes being gang raped at a frat party, how she was reduced to

an object and referred to as an “it.” In her essay, Gay implores her readers to

think long and hard on that word, to let that “it” haunt us.

What does it mean to acknowledge that our bodies are all that we are?

And where does this “it” stand in relation to the droves of young,

female pop stars today commanding us to look at “it,” to check “it,” to

smack “it,”—“it” being, in this case, their twerking behinds?

To

some, these close up images of the booty dehumanize and victimize women,

reducing us to sexual playthings. But I actually see something else here: a

reclaiming of the “it,” a defiant assertion of bodily autonomy, a demand for women

to be able to be as big and sexual as we damn well please.

The recent big booty craze is still fashion, of course, and some aspects

of the current trend, from Miley Cyrus’s use of black women as props in her

2013 VMA performance to Kim Kardashian’s photo spread for PAPER Magazine, are

infuriatingly disrespectful to black women in particular. And, of course, while

songs like Meghan Trainor’s “All About That Bass” preach body positivity, the

big booty trend really only praises a particular brand of curve, one belonging

to Kim Kardashian rather than Melissa McCarthy.

Yet

there is something also exciting about the way that some female performers are

reclaiming and celebrating the female body, about the way Nicki Minaj takes parts and

pieces of Sir Mix-A-Lot’s ode to women’s backsides in “Baby Got Back” and

transforms the booty from an object to be admired to a symbol of female sexual

appetite in “Anaconda.” The playful,

kitschy, over-the-top big booty shenanigans on Nicki Minaj’s video for the song are about self-love and swagger. “You love this fat ass,” she

manically cackles. It’s that cackle—wild, unhinged, defiantly unpretty—that

made me grow to love “Anaconda,” where the big booty becomes a symbol of

excess, sexiness, and silliness, all at once. Minaj’s “Anaconda”

doesn’t offer women a kind of empowerment fantasy, where women’s sexual

liberation will bring about a feminist revolution, but it does give women the

chance to reclaim that “it”: rather than being an object of someone else’s

consumption, it becomes a symbol of female sexual appetite and power.

The same thing could be said for Beyonce’s video for “7/11” where the

self-described feminist is seen hanging around in her underwear, having fun and

being silly, throwing her hands in the air and shaking her butt. Unlike her

classic ballads, or even her sexually explicit songs about getting it on with

her husband, this video focuses instead on women just having a good time, being

as loud, ridiculous, and playful as they want to be.

For the female body to be perceived as a source of pleasure, rather than

an object that is always on the brink of violation, is an incredible subversion

of our expectations about what it means to live in that body. The act of

reclaiming a word or an image is, of course, always fraught. I’m sure many

people feel there is simply no difference between a male-gaze-centric focus on

female curves and the booty-centered fashions surfacing in all sorts of media

today. Certainly, J.Lo and Iggy Azalea’s collaboration on the video for “Booty”

is no work of high art, and is replete with product placement and traditional

artifacts of the male gaze, but the delightfully campy videos of Nicki Minaj

and Beyonce, which showcase the female body as a source of unending amusement,

happiness, and power, are in fact changing the way we see that body. They

dare us to not only appreciate greater female involvement in the creative

process, but also challenge us to see a woman’s body as something inherently

powerful—as something, which can, and should, take up space.

Arielle Bernstein is

a writer living in Washington, DC. She teaches writing at American

University and also freelances. Her work has been published in The

Millions, The Rumpus, St. Petersburg Review and The Ilanot Review. She

has been listed four times as a finalist in Glimmer Train short story

contests. She is currently writing her first book.

Before I saw Gone

Before I saw Gone

At the end of the penultimate season of Parks and Recreation, our heroine Leslie Knope gets everything—the

At the end of the penultimate season of Parks and Recreation, our heroine Leslie Knope gets everything—the

Your life is going along normally, and then it happens: you

Your life is going along normally, and then it happens: you

Alex Ross Perry’s LISTEN UP PHILIP, besides featuring Jason Schwartzman’s best acting job and wrestling remarkable turns from Jonathan Pryce and Elizabeth Moss, performs an act of kindness for its viewers. This tale of an abusive, alienated, successful novelist’s spiral into loneliness lays out, in excruciating detail, the relationship between cause and effect that can govern the shape a human life takes. In showing us, painfully clearly, the results of novelist Philip Lewis Friedman’s poor behavior, both within his own life and in the reactions of those around him, Perry advocates strongly against such behavior, making his film the equivalent of watching a Biblical punishment unfold on film. The critical reception has focused almost entirely on Philip’s meanness, and the entertainment value therein, and not on why such a story might be told. Philip’s behavior is not, in fact, the most interesting part of the film–there is no novelty in the idea of a cruel, clever writer. That story’s been told, many times, and without such a shaky camera. There is, however, a great deal of novelty and originality in holding that cruel clever writer accountable, at length, and in so doing, prodding at viewers’ consciences. The play’s the thing, after all.

Alex Ross Perry’s LISTEN UP PHILIP, besides featuring Jason Schwartzman’s best acting job and wrestling remarkable turns from Jonathan Pryce and Elizabeth Moss, performs an act of kindness for its viewers. This tale of an abusive, alienated, successful novelist’s spiral into loneliness lays out, in excruciating detail, the relationship between cause and effect that can govern the shape a human life takes. In showing us, painfully clearly, the results of novelist Philip Lewis Friedman’s poor behavior, both within his own life and in the reactions of those around him, Perry advocates strongly against such behavior, making his film the equivalent of watching a Biblical punishment unfold on film. The critical reception has focused almost entirely on Philip’s meanness, and the entertainment value therein, and not on why such a story might be told. Philip’s behavior is not, in fact, the most interesting part of the film–there is no novelty in the idea of a cruel, clever writer. That story’s been told, many times, and without such a shaky camera. There is, however, a great deal of novelty and originality in holding that cruel clever writer accountable, at length, and in so doing, prodding at viewers’ consciences. The play’s the thing, after all.

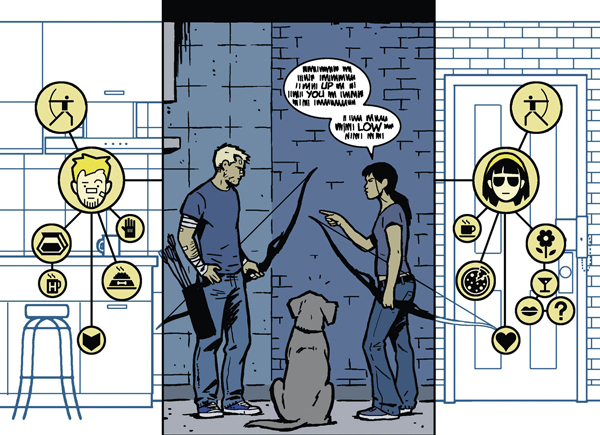

So-called “normcore fashion,” a bizarre combination of countercultural

So-called “normcore fashion,” a bizarre combination of countercultural

It’s scary to see actors age.

It’s scary to see actors age.

Spoiler Alert: The following piece contains spoilers.

Spoiler Alert: The following piece contains spoilers.