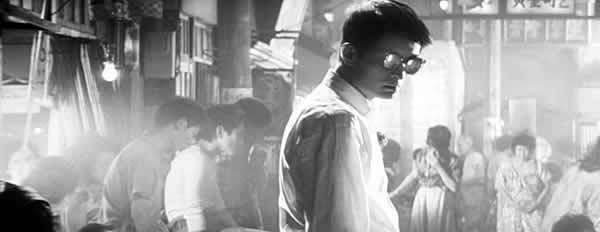

The perfect crime, the wrong man, the speeding train, and the surprising MacGuffin. High and Low has all the best elements of a great Alfred Hitchcock film. But it isn’t Hitchcock—it’s Akira Kurosawa, the Japanese director better known for his samurai flicks and complex moral tales.

When Kurosawa adapted works of Western fiction, he often chose from the greats: Shakespeare, Dostoevsky, Gorky. But High and Low (1963) is not adapted from a literary giant or even a Japanese author, but a minor 1950s American pulp novel entitled King’s Ransom by Ed McBain. King’s Ransom was part of a series of novels following the stories of the 87th police precinct, and while it has its literary qualities, the novel’s style bears no resemblance to the serious tone and moral complexity of Kurosawa’s film.

However, one director in Western cinema made his entire career through the meshing of high and low art: Hitchcock. The master’s reputation stemmed from spinning popular murder and suspense stories while engaging critics and scholars with morbid and psychological themes. High and Low feels as much indebted to Hitchcock as Kurosawa’s samurai films show the influence of John Ford’s westerns. Like Hitchcock, Kurosawa explores the roles of duality, ubiquitous guilt, and the incapacity to understand evil in a frightening and ultimately despairing fashion. High and Low ultimately paints a disturbing portrait of humanity, where evil simply exists within each person without explanation, creating a world similar to the sadistic one Hitchcock often presented.

The film seems ripe for comparison to Hitchcock from the opening shot, as the camera never leaves the home of Gondo. Like Rope, Lifeboat, Dial M for Murder, and especially Rear Window, Kurosawa limits himself by never staging a sequence outside of Gondo’s mansion—even the credits are framed from the large window looking down. Other classic Hitchcock tropes play large roles in the film: a train—essential in the narratives of North by Northwest and Shadow of a Doubt—literally bridges the two sections of the film. And we can see intense shadows, symbolic staircases, voyeurism, and grotesque death, other Hitchcock trademarks.

But High and Low’s most noted motif is the use of doubles and opposites as a sign of similarities between good and evil. Strangers on a Train, Shadow of a Doubt, Frenzy, and countless other Hithcock works explored this topic, and Kurosawa forges the same relationship between Gondo and Takeuchi. Kurosawa foreshadows the duality with the use of the two children, who are so identical that Gondo’s wife confuses them when they switch clothes while playing cops and robbers. The children’s outer appearance might suggest their societal roles, but under the surface, both Gondo and Takeuchi are both conniving and malicious—Gondo simply confines his immoral practices to business.

Kurosawa builds this philosophy into the film’s structure. Like Hitchcock’s Psycho, the narrative breaks into two parts with a protagonists in the center of each part. The film’s first half centers around Gondo and his moral dilemma of whether to save Shinichi. The second half of the film focuses on Takeuchi, operating on an opposing plane. Set in multiple locations, often with crowded frames, the genre of the film changes from morality play to police procedural in this part. The film bears down on Takeuichi’s story—his background, identity, and methodology—as the cops investigate and arrest him. When Gondo and Takeuchi meet face-to-face in the film’s final scene, Kurosawa uses the glass to literally reflect their faces onto each other, a technique that recalls the penultimate shot of Psycho as Norman’s mother’s face is superimposed over Norman’s.

So why does such a fate fall on Gondo? In High and Low, the kidnapping narrative is not just set up as coincidence, but as a fate that Gondo is punished for. As soon as the Osaka deal is set, Takeuchi calls almost immediately with news of the kidnapping. The placement of the phone is made to seem not like coincidence but fate—even one of the rival businessmen later reflects that it was “divine retribution.” Gondo hasn’t done anything terribly wrong, but he does recall Roger Thornhill in North by Northwest.. Before Thornhill becomes a case of mistaken identity (as Shinichi is here), we watch him pretending his secretary is ill, to grab a taxi quicker. Thornhill likes playing pretend, and thus his punishment is an extreme version of that.

Plus, Gondo’s not the only one to be punished. During the first half, Akoi, Gondo’s driver, seems like a humble man who deserves to have his son back. But in the second half, we see how poorly he treats his child, and that perhaps deserves the shame. And during the film’s harrowing alley sequence, we watch an addict suffer at the hands of Takeuchi. Her death seems inevitable, but it only happens because the police, the men responsible with her protection, allow it to happen so they may arrest Takeuchi. As Kurosawa’s camera shoots up to reveal her discarded body on the floor, he reveals that the height of evil is also its lowest point.

These ubiquitous punishments of the not-so-innocent relate to the worldview that both Hitchcock and Kurosawa seem to subscribe to: an evil that is ever prevalent and simply incapable of explanation. In Hitchcock, evil is often presented as kindness and without any precise motivation. Psycho’s famous psychiatrist speech has always had a humorous tone to it, more than one of essential exposition. And what motivation could one even begin to ascribe to the titular animals of The Birds?

In the second half of the film, the main narrative tension derives from the mystery surrounding the identity of the kidnapper and his rationale. The fact that High and Low leaves the spectator with an unsatisfactory answer is only more significant in examining the evil that surrounds the film. Takeuchi turns out to be a simple medical intern who is also a drug dealer, but nothing establishes him as a unique case. In the last sequence, he reveals that he wanted Gondo present to show that he was not afraid to die, but he soon screams in anguish, making him more pathetic than villainous.

The final moment in High and Low, where Gondo stares at his own image, answers the question of where such evil lies. Hitchcock suggested this answer too, but so often, his endings left us with a smile. Kurosawa never mentioned the influence of Hitchcock in any of his interviews, but I can’t imagine watching this modern day crime story and not think of the master of suspense. Kurosawa may have seen Hitchcock’s cinema, but instead of exiting the theater with a smile, he would have left with a chilled face.

And whatever happened to Ed McBain, the author who inspired this masterpiece? His real name was Evan Hunter, and he went on to write a little film called The Birds.

Peter Labuza is a film writer in New York City, originally from Minnesota. He has written for Indiewire, Film Matters, the CUArts Blog, the Columbia Daily Spectator, and MNDialog. He will be attending Columbia University in the fall for a Master in Film Studies, focusing on the history of American film genres. He currently blogs about film at www.labuzamovies.com. You can also follow him on Twitter.

Click here to donate to the NFPF!

In 2011, the New Zealand Film Archive discovered part of The White Shadow, a film directed by Graham Cutts, and written, edited, and assistant directed by the legendary Alfred Hitchcock. The first three reels of this lost work have been arduously restored, but the film has only had a single public screening. For this year’s For the Love of Film: The Film Preservation Blogathon, we are asking for donations to the National Film Preservation Foundation. If we can raise $15,000, the Foundation will provide free streaming of The White Shadow for four months, and record a new score by Michael Motilla. To donate, simply click here. And for more information on the blogathon, please visit Ferdy on Films, the Self-Styled Siren, and This Island Rod. Every donation counts, and we thank you for your continued support of film.

Moonrise Kingdom is a great success, both within the context of Wes Anderson's body of work and as a work unto itself. Initially, however, its Wes- Anderson-y-ness is almost off-putting. At the start of this very mature children’s romance about two pre-teens, the camera tracks through almost every room of a house; the separate but equal nature of each of the house’s various inhabitants is matched with a song from a child’s record, explaining how an orchestra's sections come together to perform a piece by British composer Benjamin Britten.

Moonrise Kingdom is a great success, both within the context of Wes Anderson's body of work and as a work unto itself. Initially, however, its Wes- Anderson-y-ness is almost off-putting. At the start of this very mature children’s romance about two pre-teens, the camera tracks through almost every room of a house; the separate but equal nature of each of the house’s various inhabitants is matched with a song from a child’s record, explaining how an orchestra's sections come together to perform a piece by British composer Benjamin Britten.