In 2001, Steven Spielberg went apocalypse crazy and he never recovered. 2001 was when he froze the world in in A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, followed by War of the Worlds, followed by the legacy-soiling Transformer toy-apocalypse line, more alien end times in Falling Skies, and the failed eco-Holocaust/Jurassic Park mash-up of Terra Nova—and was he done? No, he was not.

He will soon be destroying the world again in a remake of the original SF Armageddon, 1951’s When Worlds Collide, and an adaptation of Daniel H. Wilson’s robot apocalypse, Robopocalypse.

Still, the question isn’t “Why?” so much as, “What took him so long?”

One can only guess, so I will. One thing that rose from the debris of 9/11 was a need to process ambient terrors, of which there were suddenly so many. A new genre created itself from bits and pieces of other genres, in true Doctor Frankenstein fashion. And there’s always big money in salving inarticulated jitters—just ask Spielberg.

And so, by my rough count, over seventy-five films and TV shows have congealed over the last decade to form an actual new subgenre, or series of interconnected subgenres, complete with shared repeating narrative patterns and modes of obliteration.

How does the world end? By nuclear means (28 Days Later), by plagues (Contagion), vampires (Stake Land), zombies (The Horde), aliens (Returner), natural threats (The Happening), and sundry Biblical agita (Jerusalem Countdown).

The subgenre has developed certain stylistic defaults: for example, heavy gray murk and raining ash, as in the indie post apocalypse road picture, The Road, and populist films like Terminator: Salvation and Book of Eli. We also have apocalypse-film go-to actors: Willem Dafoe moves effortlessly from Michael and Peter Spierig’s populist vamp actioner Daybreakers to Abel Ferrara’s self explanatory art house effort, 4:44: Last Day on Earth, while Sarah Polley, eternally wan, affectless and snarky, stared in 1998’s seminal indie end timer, Last Night, which added dot.com-style yawns to the Armageddon reactive syntax, and the remake of Romero’s pre-apocalypse classic, Dawn of the Dead.

Most fascinatingly, this new subgenre has split into what I’ll call indie and populist apocalypse films, each with radically differing sensibilities, aesthetics, and values.

First, the indie apocalypses. The indies are largely by, about, and for upscale, highly educated, older white people fortunate enough to enjoy the luxury of feeling a weary, ambient disappointment, born of under-appreciated entitlement. Inevitably, this leads to the valuing of the canon over the new, the ‘introspective’ over the vibrant, and, to bring us back to where we started, to what Spielberg is up to: staying lively, even if that means blowing up the world.

In the populist apocalypse films, anyone, of any class or any gender, can be a hero. She can be a genetically modified lab experiment turned anti-corporate leader, (see Paul Anderson’s Resident Evil: Afterlife). She can be a boy survivor of Earth’s decimation with a second chance on another planet (see Titan, A.E.). Or, possibly, in a few years from now, while the world is falling apart, a starving, ruined slip of a girl taking down a fascist government, one arrow at a time, in the last of the Hunger Games films.

Anyway, while she may not make it to the end credits, the pop-apocalyptic hero’s efforts will not be for naught, and our entertainment budget will not be blown on a solipsistic nihilism fantasy.

And so, for your approval—or not—five films from the indie and populist sides of the Armageddon divide. Although I clearly have my issues with the indie cause, I’ve tried to include the best—or most interesting—of the subgenre.

INDIE ARMAGEDDON!

4:44: Last Day on Earth (2012)

So nobody listened to Al Gore, and now some unspecified, global—but prompt!—atmospheric disaster will destroy the world at exactly 4:44 EST, in Abel Ferrara's new film.

So nobody listened to Al Gore, and now some unspecified, global—but prompt!—atmospheric disaster will destroy the world at exactly 4:44 EST, in Abel Ferrara's new film.

As if continuing the role of the drug dealer he played in Paul Schrader’s Light Sleeper, Willem Dafoe is Cisco, a recovering addict with a super younger painter girlfriend named Skye. She’s played by Shanyn Leigh, the director’s real-life GF, which adds a layer of hermetic creepiness. Her paintings, big splashes of bold organized color are a true relief from the drab, mauve-ish digital video tones that give the movie a vanity project emptiness broken only by stock footage of riots, the Dalai Lama and other random elements.

In true boomer fashion, the End is really all about Cisco. So after bedding Skye, he mumbles to the heavens, wanders around Essex Street on the Lower East Side to see if—like the wild Ferraro of Ms. 45, Bad Lieutenant, and The Addiction—he will be able to stay literally/figuratively sober long enough to find some friends with whom he can talk about himself. Then he comes home, and the world ends.

Thing about these movies, you don’t have to worry much about spoilers.

They Came Back (2004)

They Came Back takes the flesh-eating out of the zombie film model; what's left is a nightmarish allegory of elderly hospice care that never ends.

They Came Back takes the flesh-eating out of the zombie film model; what's left is a nightmarish allegory of elderly hospice care that never ends.

In a French village, the dead return. They seem the same. Almost. Sort of. But then they start gathering at night, silently, doing . . . what?

Robin Campillo’s unnerving film bounces real world fears into a fog of classic, Val Lewton-style quiet horror. The camerawork is stealthy, but like many indie apocs you wonder why color is such a villain in the director’s mind.

Still, the atmosphere and implication stabs home some cold questions: How long before the dead use up too many jobs, resources and space rightfully allotted to the young or healthy? How much care is too much care?

They Came Back also entertains a spiritual dimension that’s truly scary. It’s also revealing in the sense that it reminds us how self-limiting left-leaning indie film has chosen to be.

Melancholia (2011)

Both a balm and a reveal of a classic Romantic sensibility at work behind Lars von Trier's mad Dane image, Melancholia limns depression as an elemental power that rips the planets out of line and threatens to sever the connection between two sisters. There's Justine (Kirsten Dunst), a major depressive getting married in the grand style, and Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), slender and always frightened.

Both a balm and a reveal of a classic Romantic sensibility at work behind Lars von Trier's mad Dane image, Melancholia limns depression as an elemental power that rips the planets out of line and threatens to sever the connection between two sisters. There's Justine (Kirsten Dunst), a major depressive getting married in the grand style, and Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), slender and always frightened.

And then there’s a planet—called “Melancholia”, no less—hurtling, When Worlds Collide-style, towards Earth, and Claire has no choice but to do the most terrifying thing: to ask for what she needs from a sister who delights in cruelty.

Most of all, this is rapturously beautiful, the natural universe as a cruel, loving, and insane mother-tormentor figure. Obliterated in the first and last images by Melancholia’s impact, but united by Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde” and the sisters’ recurrent hand-holding, this is von Trier filming his way out of malady back to our world—and at 56, just starting a whole new peak of his career.

The Road (2009)

So, something destroyed all life on Earth. The skies are grey, trees black and spindly, buildings in advanced decay. The world, in John Hillcoat's vision, looks like a 90s black metal album cover.

So, something destroyed all life on Earth. The skies are grey, trees black and spindly, buildings in advanced decay. The world, in John Hillcoat's vision, looks like a 90s black metal album cover.

Filthy, wretched, starving, fifty-something Poppa (Viggo Mortensen) and his filthy, wretched, starving Boy (Kodi Smit-McPhee) are wandering South, and that’s what you’re going to be seeing for 111 minutes. The only reprise comes in the form of 30-second sunny dreams of Man's wife (Chalize Theron).

Aside from starvation and the elements, the biggest threat is from cannibal attack. As luck would have it, Man and Boy stumble upon an old southern mansion with a basement full of naked, crazed people . . . who are being warehoused as food.

Excuse my flippancy, but The Road’s cloying high seriousness, its saccharine Nick Cave score, and its studied miserablism can't hide the fact that The Road is one genre step away from being a zombie movie, which is why I suppose they eliminated the famed baby-roasted-on-a-campfire-spit scene which appeared in Cormac McCarthy's original book.

The Last Days of the World (2011)

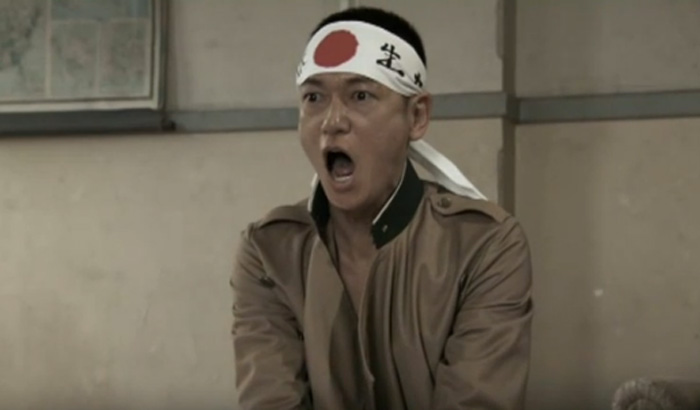

Thanks to Japan's manga culture, we finally got an indie end time film with young people in it. Based on Naoki Yamamoto’s cult manga, The Last Days of the World tells of Kanou (Jyonmon Pe), a seventeen-ish schoolboy busy hating life when a half-foot high God in a top hat shows up to tell him the world will be ending soon.

Thanks to Japan's manga culture, we finally got an indie end time film with young people in it. Based on Naoki Yamamoto’s cult manga, The Last Days of the World tells of Kanou (Jyonmon Pe), a seventeen-ish schoolboy busy hating life when a half-foot high God in a top hat shows up to tell him the world will be ending soon.

And so Kanou kidnaps his crush, Yumi (Chieko Imaizumi), steals a car, tries to sexually attack Yumi with mayonnaise (don’t ask), finds a cult devoted to cos-play (dressing up in manga costumes), as a life-hating cop kills people while in pursuit of the pair. And sometimes a talking dog, or their car, might remind Kanoe that The End is Nigh.

Eiji Uchida’s sometimes funny nihilist travelogue wants to be Donnie Darko, suggesting Miike’s Gozu, but it lacks the latter’s passionate nuttiness. It’s also bereft of any music beyond a stumbling two-chord guitar flourish, or any color beyond a dull palette of liver-lavenders, greys and spoiled mauves. Uchida’s film is already dead: the end of the world is a mere formality.

POPULIST ARMAGEDDON!

Pandorum (2009)

At the start of the film, the crew of a huge starship wakes from hyper-sleep with severely compromised memories.

At the start of the film, the crew of a huge starship wakes from hyper-sleep with severely compromised memories.

The ship—apparently designed by a firm headed by Philippe Starck, H.R. Giger and H.P. Lovecraft—slowly reveals itself to be infested by shadow-dwelling monstrosities, but this is blamed on a mind-malady called "pandorum."

As more sleepers awake and promptly die horribly, we realize that the starship has been at the bottom of another planet’s ocean for hundreds of years after Earth’s destruction, and that Christian Alvart’s relentlessly nerve-wracking film is, like Carpenter’s The Thing, about trust among the working class. Unlike Carpenter’s film, it ends with a very tentatively hopeful gesture.

Dollhouse, “Epitaph Two: Return” (2009)

Joss Whedon’s Dollhouse starred Eliza Dusku as Echo, a ‘doll’ implanted with an endless array of personalities with as many skills who are hired by the rich, corrupt and despicable for various purposes. After a dumbed-down first season that felt like a surreal, sub-par Alias with muted anti-objectification subtext, Fox left Whedon alone. The result: the bleakest show in network history.

Joss Whedon’s Dollhouse starred Eliza Dusku as Echo, a ‘doll’ implanted with an endless array of personalities with as many skills who are hired by the rich, corrupt and despicable for various purposes. After a dumbed-down first season that felt like a surreal, sub-par Alias with muted anti-objectification subtext, Fox left Whedon alone. The result: the bleakest show in network history.

Men ‘nested’ inside women's memories like cancers. ‘Dolls’ blew their brains out to stop becoming what men wanted, or were brain-wiped and stored in an ‘Attic’ like, well, broken dolls.

“Epitaph” suggests where Whedon would have gone with a third season. It’s 2020. Corporate misuse of Dollhouse technology has turned the world into a wasteland. Clutches of people know who they are; others have built agrarian lives built on false memories.

Echo and a small group of survivors believe that a pulse weapon can destroy all imprinting and return humanity to their real selves.The Onion’s Noel Murray compared Dollhouse’s artistic growth to “MacGyver [who] gradually morphed into Battlestar Galactica." Yep.

I Am Legend (2007)

For all Robert Neville knows, he’s the last man in Manhattan after an attempted cancer cure decimated most of the city’s population, save nocturnal “Daykseekers” that feed on those immune to the virus.

For all Robert Neville knows, he’s the last man in Manhattan after an attempted cancer cure decimated most of the city’s population, save nocturnal “Daykseekers” that feed on those immune to the virus.

Neville—played with grace and gravity by Will Smith in what will be remembered as his greatest role—is an Army doctor who doesn’t give in to despair even as it tears at him.

Director Francis Lawrence takes shots of almost Malick-ian stillness in long shots of a strangely sylvan dead city, rendered in computer-assisted views of Manhattan landmarks overgrown with Nature softly amuck. There’s the tiny alien effect of being able to hear Neville’s German Shepard sniffle where once crowds would dwarf his loudest bark. Smith portrays the alienation, fear, and loneliness of his situation beautifully, while never going for pitiful. And that ending—what’s wrong with nobility again?

Priest (2011)

Somewhere in an unspecified post-apocalypse wasteland, The Church is led by a corrupt monsignor (Christopher Plummer) who rules with an iron Christian fist in the middle of a war between vampires and humans.

Somewhere in an unspecified post-apocalypse wasteland, The Church is led by a corrupt monsignor (Christopher Plummer) who rules with an iron Christian fist in the middle of a war between vampires and humans.

When a lovely young girl (Lily Collins) is kidnapped by rogue vampires, led by an uber-vamp Black Hat (Karl Urban), who doesn’t know the girl is the niece of a vamp-hunter named Priest (Paul Bettany), all hell breaks loose.

Before you know it, our rockin’ man of the cloth with the upside down crucifix face tattoo (!) is on his ultrasonic nitrocycle to save Lucy and teach Plummer a thing or two, eventually teaming with a priestess badass (Maggie Q).

Directed by Scott Stewart as if he lost his mind after watching The Searchers, Priest is the real successor to the Mad Max films, with about twenty gallons of sizzling sacrilegious transgression thrown in just because they could, and also the alien luster in Don Burgess’ purposefully monocolor images, as a gorgeous bonus feature.

Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles (2008-9)

Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles was the most conceptually daring television entry in the canon since the first film in 1984. Predictably, Fox axed it after a paltry thirty-one episodes.

Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles was the most conceptually daring television entry in the canon since the first film in 1984. Predictably, Fox axed it after a paltry thirty-one episodes.

Lena Headey took the titular role as the badass mother of John Connor, aka the man who will save us all from the world-destroying Terminators. Connor, meanwhile, is played by Thomas Dekker.

Guaranteeing the show its eternal place in Queer Media Studies is the other "woman" of the Conner household–a "good" Terminator dedicated to John’s survival. Her name is Cameron, and she's played by Joss Whedon regular Summer Glau in a hilariously discombobulated performance.

Showrunner Josh Friedman deftly ran this odd alt.family through plot lines that juggled Fugitive tropes, bits of bizarro-world domestic comedy, SF time paradoxes and action film storytelling—but what’s compelling now is the way its anti-corporate storylines mirror the general exhaustion of the Cheney era’s end.

Ian Grey has written, co-written or been a contributor to books on cinema, fine art, fashion, identity politics, music and tragedy. Magazines and newspapers that have his articles include Detroit Metro Times, gothic.net, Icon Magazine, International Musician and Recording World, Lacanian Ink, MusicFilmWeb, New York Post, The Perfect Sound, Salon, Smart Money Magazine, Teeth of the Divine, Venuszine, and Time Out/New York.

Funny Games (1997) This is an obvious riff on the “remote control” moment that follows the shot chosen here, but with the aim to dissect one of the film’s most disturbing moments (that’s also the most cheer-inducing for the audience). Instead of blood and guts exploding from Frank Giering’s midsection, we see some special effects paraphernalia: a safety pack on his belly to protect him from exploding gunpowder, and some impressive coordination between the explosion effects both in front of and behind him. What’s also impressive is his posture as he receives the blow. Most people would flinch, cower, or curl, but Giering stands erect, practically heroic; all the better for the particles to fly from his chest.

Funny Games (1997) This is an obvious riff on the “remote control” moment that follows the shot chosen here, but with the aim to dissect one of the film’s most disturbing moments (that’s also the most cheer-inducing for the audience). Instead of blood and guts exploding from Frank Giering’s midsection, we see some special effects paraphernalia: a safety pack on his belly to protect him from exploding gunpowder, and some impressive coordination between the explosion effects both in front of and behind him. What’s also impressive is his posture as he receives the blow. Most people would flinch, cower, or curl, but Giering stands erect, practically heroic; all the better for the particles to fly from his chest.

Yet, for a director who addresses such heavy themes in his work, Anderson himself remains an enigma. His public persona—sporting a hipster-ish corduroy and scarf-laden wardrobe—suggests that he is quiet, quirky, and undeniably cerebral. His films all

Yet, for a director who addresses such heavy themes in his work, Anderson himself remains an enigma. His public persona—sporting a hipster-ish corduroy and scarf-laden wardrobe—suggests that he is quiet, quirky, and undeniably cerebral. His films all

So nobody listened to Al Gore, and now some unspecified, global—but prompt!—atmospheric disaster will destroy the world at exactly 4:44 EST, in Abel Ferrara's new film.

So nobody listened to Al Gore, and now some unspecified, global—but prompt!—atmospheric disaster will destroy the world at exactly 4:44 EST, in Abel Ferrara's new film. They Came Back takes the flesh-eating out of the zombie film model; what's left is a nightmarish allegory of elderly hospice care that never ends.

They Came Back takes the flesh-eating out of the zombie film model; what's left is a nightmarish allegory of elderly hospice care that never ends. Both a balm and a reveal of a classic Romantic sensibility at work behind Lars von Trier's mad Dane image, Melancholia limns depression as an elemental power that rips the planets out of line and threatens to sever the connection between two sisters. There's Justine (Kirsten Dunst), a major depressive getting married in the grand style, and Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), slender and always frightened.

Both a balm and a reveal of a classic Romantic sensibility at work behind Lars von Trier's mad Dane image, Melancholia limns depression as an elemental power that rips the planets out of line and threatens to sever the connection between two sisters. There's Justine (Kirsten Dunst), a major depressive getting married in the grand style, and Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), slender and always frightened. So, something destroyed all life on Earth. The skies are grey, trees black and spindly, buildings in advanced decay. The world, in John Hillcoat's vision, looks like a 90s black metal album cover.

So, something destroyed all life on Earth. The skies are grey, trees black and spindly, buildings in advanced decay. The world, in John Hillcoat's vision, looks like a 90s black metal album cover. Thanks to Japan's manga culture, we finally got an indie end time film with young people in it. Based on Naoki Yamamoto’s cult manga, The Last Days of the World tells of Kanou (Jyonmon Pe), a seventeen-ish schoolboy busy hating life when a half-foot high God in a top hat shows up to tell him the world will be ending soon.

Thanks to Japan's manga culture, we finally got an indie end time film with young people in it. Based on Naoki Yamamoto’s cult manga, The Last Days of the World tells of Kanou (Jyonmon Pe), a seventeen-ish schoolboy busy hating life when a half-foot high God in a top hat shows up to tell him the world will be ending soon. At the start of the film, the crew of a huge starship wakes from hyper-sleep with severely compromised memories.

At the start of the film, the crew of a huge starship wakes from hyper-sleep with severely compromised memories. Joss Whedon’s Dollhouse

Joss Whedon’s Dollhouse For all Robert Neville knows, he’s the last man in Manhattan after an attempted cancer cure decimated most of the city’s population, save nocturnal “Daykseekers” that feed on those immune to the virus.

For all Robert Neville knows, he’s the last man in Manhattan after an attempted cancer cure decimated most of the city’s population, save nocturnal “Daykseekers” that feed on those immune to the virus. Somewhere in an unspecified post-apocalypse wasteland, The Church is led by a corrupt monsignor (Christopher Plummer) who rules with an iron Christian fist in the middle of a war between vampires and humans.

Somewhere in an unspecified post-apocalypse wasteland, The Church is led by a corrupt monsignor (Christopher Plummer) who rules with an iron Christian fist in the middle of a war between vampires and humans. Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles was the most conceptually daring television entry in the canon since the first film in 1984. Predictably, Fox axed it after a paltry thirty-one episodes.

Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles was the most conceptually daring television entry in the canon since the first film in 1984. Predictably, Fox axed it after a paltry thirty-one episodes.