Among its army of cult followers, A Confederacy of Dunces is the funniest American novel ever written. Little surprise, then, that the recent leaked news of yet another attempt to adapt it to the big screen after thirty years of failure—with Zachary Galifianakis in the lead role—was greeted ecstatically by the book’s fans. But enormous obstacles remain in translating the unusual book to screen, including, most of all, whether Galifianakis has the ability to capture its one-of-a-kind antihero, Ignatius J. Reilly, in a way no one has ever done.

The story of the book’s path to publication is extraordinary. A gifted young New Orleans writer named John Kennedy Toole wrote A Confederacy of Dunces in the early 1960s. Toole couldn’t get it published, and, falling into deep depression from his general lack of success, killed himself in 1969 at age 32.

Several years after his death, his mother discovered the only remaining copy of the Confederacy manuscript in a box in his room. Determined to prove her son’s brilliance, she submitted the book to several publishers, meeting with rejection until she approached the great southern writer Walker Percy in 1976. Showing up unannounced at his office at Loyola University, she dumped the massive, barely legible draft in his hands and demanded he read it. Percy, who describes the incident in the book’s foreword, astonishingly not only read it but loved it. With his prodding, Louisiana State University Press published it in 1980 with a small print run, not expecting a profit. The rest is history: Confederacy earned national critical attention, won the Pulitzer Prize, and has sold millions of copies.,

The book’s path to Hollywood has not had a similar ending . . . yet. After Confederacy’s release, Scott Kramer, a young executive at 20th Century Fox, immediately bought its rights and set out to get the movie made. In 1982, he nearly signed John Belushi to star—after several amusing face-to-face meetings where the prickly star repeatedly forgot who Kramer was—but Belushi died shortly before a deal could be consummated. Since then, such luminaries as Kramer, Johnny Carson, and John Langdon have tried to get the project made, with stars attached including John Candy, Chris Farley, John Goodman, and Will Farrell, as well as directors Harold Ramis and Steven Soderbergh, but none of the productions have ever gotten off the ground.

Of Confederacy, Will Farrell has said, “It’s a movie everyone in Hollywood wants to make, but no one wants to finance.” He may be right, but that’s only a small piece of the story. Other challenges relate to the book’s structure, specifically its language (which is unique to blue collar New Orleans), time period (ostensibly set in the early 1960s), and unusual plot layout (or really, its lack thereof). A big part of the book’s charm, indeed, lies in its language, which many Louisianans have long praised for its accuracy in capturing the region’s accents, something Toole seemingly acknowledged to his future readers in the beginning of the book: “’Oh, Miss Inez,’ Mrs. Reilly called in that accent that occurs south of New Jersey only in New Orleans, that Hoboken near the Gulf of Mexico.” (This was also observed by Percy in a letter to Toole’s mother: “[Confederacy has] an uncanny ear for New Orleans speech and a sharp eye for place (I don’t know of any novel which has captured the peculiar flavor of New Orleans’ neighborhoods as well).”). First-time readers may take some time to get used to this language, but it’s hardly unintelligible: it’s an integral ingredient in creating the strange world of the novel, and it wouldn’t have to be changed to be understood or be funny. Take, for example, the main character’s description to his mother of an altercation at work: “I had a rather apocalyptic battle with a starving prostitute,” Ignatius belched. “Had it not been for my superior brawn, she would have sacked my wagon. Finally she limped away from the fray, her glad rags askew.”

Time period is also a potential challenge, but one that can be fairly neatly addressed. For the most part, the book makes almost no direct reference to its time, with the only clues revealing it based on the movies Ignatius goes to throughout the book (“When Fortuna spins you downward, go out to a movie and get more out of life”). When the adaptation actually takes place, then, is potentially flexible; a good film could take place in 1962 or 2012 and still capture the book’s spirit. In fact, it seems likely, both because of cost considerations and Ignatius’s loathing of the modern world, that the adaption would be set in the present, to make Ignatius’s pathology more timely and relatable.

Implementing Confederacy’s plot would be harder. For all of its gifts, the book is a highly unconventional narrative with no real plot. Not that there's anything wrong with that, but this why Toole had such a tough time finding a publisher in the 1960s, and why any adaptation would be a challenge.

This problem was recognized by Simon & Schuster’s Robert Gottlieb. Gottlieb, who would go on to become the Editor-in-Chief at The New Yorker and the top editor at Knopf, corresponded with Toole over two years in the mid-1960s. He admired the book but repeatedly observed its lack of plot, something he noted in his first letter to Toole: “[Confederacy] must be strong and meaningful all the way through—not merely episodic . . . . In other words, there must be a point to everything in the book, a real point, and not just amusingness that’s forced to figure itself out.”

Considering its level of success, Gottlieb clearly underestimated Confederacy’s broader appeal, but his criticism remains apt. Despite Ignatius’s epic misadventures and squabbles, his personal story doesn’t follow a regular arc. This lack of direction is even more pronounced with the other characters: Ignatius’s antagonist, Myrna Minkoff, who isn’t actually seen until the novel’s final scene, the sardonic Burma Jones, the nasty bar owner Lana Lee and her dopey aspiring stripper Darlene, Patrolman Mancuso and his aimless “quest” to make an arrest, the pitiful denizens of Levy Pants, Claude Robichaux and his hatred of “communisses,” and others have no realizable goals—they’re all just drifting through the story. Make no mistake: their exploits are fantastic, but they lack real depth or meaning and would thus largely have to be filled out in a film—where, unlike in a novel, a character's actions must be seen and not just surmised.

Still, no book adapted to film is retained in its entirety, and writers must cut, amend, or remake entire scenes or segments. While in Confederacy’s case, the plot work to be done will be more immense – creating an individual drive for virtually each of the characters—and has likely been a factor in the repeated adaption failures, it’s not unreasonable to expect from a crack writer. Furthermore, as there is no single framework for a movie, Confederacy could come out as more episodic and less plot-driven; though many details would need to be creatively crafted from scratch.

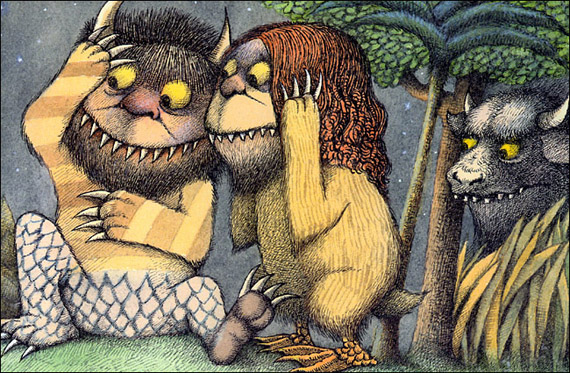

Instead, the biggest difficulty in adapting Confederacy comes from the unparalleled main character. It is not hyperbole to describe Ignatius Reilly, the massive, flatulent, obese, obscene, delusional, curmudgeonly, masturbatory, habitually unemployed, and unemployable medieval philosopher layabout as a character with few parallels anywhere in American letters. He is Toole’s most magnificent creation, the novel's center and its most appealing part.

Every reader knows Ignatius is a fool, as does every character with whom he crosses paths; the only person who doesn’t realize this is Ignatius himself, which is what would make any portrayal of him so complicated. Just beneath Ignatius’s hapless appearance, questionable sanity, and miserable tenure as a hot dog vendor is an unshakable dignity: we may see him as a clownish pariah, but Ignatius believes, no, knows he is a genius and a revolutionary, and it is the rest of the world—businessmen, police officers, gays, Protestants, beatniks—that ignores his wisdom at its own peril. Preserving this dignity while at the same time capturing Ignatius’s rants and pratfalls would require a tough balancing act.

To portray him as simply a bumbling fat-ass who lives with his mother might earn some cheap yucks, but it would ignore Ignatius’s true greatness. This approach marks the fate Confederacy fans should fear most given the substandard comedies being churned out in recent years; I can just see a preview ad with a mustached, bloated Ignatius falling over and farting in a coarse resemblance to the tired slapstick of the recent ghastly-looking Three Stooges flop.

The newest adaptation attempt is at least in good hands. The helming producer, Scott Rudin, is one of the most respected and intelligent men in Hollywood today (The Social Network, There Will Be Blood, The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo), with a reputation for taking on tough projects (including, for example, plans to adapt some of the most complex novels of William Faulkner and Cormac McCarthy). Rudin’s selection of Zach Galifianakis to play Ignatius is evidence that the filmmaker is on the right track. Confederacy with Will Farrell would have been a painful disaster: besides lacking the all-important physical look, Farrell’s one character, the Ricky Bobby-Ron Burgundy-Frank the Tank-George W. Bush idiot may lack self-awareness, a deficit which would be key to portraying Ignatius, but it’s a tired, one-dimensional act which couldn’t capture Toole’s subtlety. John Candy, who thrived in kindly roles in Uncle Buck and Planes, Trains and Automobiles would have been too soft-edged, and the great Chris Farley, most clearly in Tommy Boy and defining roles like SNL motivational speaker Matt Foley, too loud and purely physical to pull it off.

Less comedically narrow, Galifianakis is a better fit for the role. Besides sharing Ignatius’s girth, tangled facial hair, swarthy visage, and panting physique, Galifianakis can also be funny in a mild manner, something he exhibited well in The Hangover as Alan, a pathetic, creepy weirdo who nonetheless doesn’t realize his eccentricity or others’ disgust for him. Galifianakis also acts with a disguised but pointed bitterness, conveying an anger at the world which doesn’t come off as so biting and hostile that it overwhelms his comic effectiveness, and which would be a critical component to capturing Ignatius’s crusade against the world. Galifianakis’s acting resume is thinner than those other top comic actors, but with Belushi and Oliver Hardy long gone, he seems by far the best man to balance Toole’s story with Ignatius’s misplaced dignity and soft, harmless fury.

If Confederacy finally gets made, fans everywhere will be hoping he can do it.

Mark Greenbaum's work has appeared in The New York Times, Salon, The LA Times, The New Republic, and other publications.

Listening to Haskell speak about the film conjures visions

Listening to Haskell speak about the film conjures visions

The Other Woman may be the most disturbing episode of Mad Men ever. We've seen bad things happen to characters we love, some of their own doing. We've seen Don drink himself into a stupor, Roger lie the company almost into ruin, and Lane embezzle. We've seen the way both ambition and love can cause people to sacrifice themselves, but has anyone suffered more than Joan, or sacrificed more?

The Other Woman may be the most disturbing episode of Mad Men ever. We've seen bad things happen to characters we love, some of their own doing. We've seen Don drink himself into a stupor, Roger lie the company almost into ruin, and Lane embezzle. We've seen the way both ambition and love can cause people to sacrifice themselves, but has anyone suffered more than Joan, or sacrificed more?

The "Welcome to Bushwick" part is easy: it's the location of a big loft party where all of our main characters converge

The "Welcome to Bushwick" part is easy: it's the location of a big loft party where all of our main characters converge