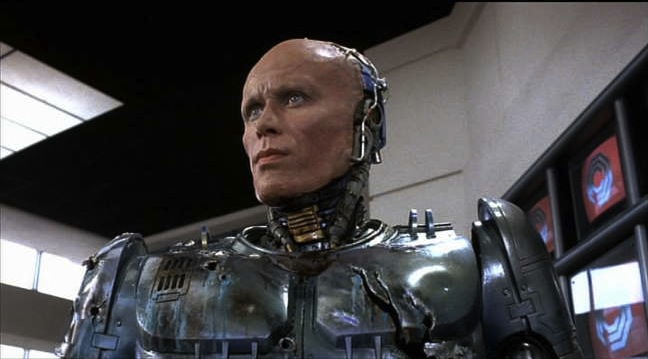

The "Cruel Summer" series of articles examines influential movies from the summers of the 1980s. The previous entries in the series have covered THE BLUES BROTHERS (1980), STRIPES (1981), ROCKY III (1982), WARGAMES (1983), PURPLE RAIN (1984), PEE-WEE'S BIG ADVENTURE (1985), TOP GUN (1986), and ROBOCOP (1987).

The 1980s were dominated by action movies. Previous decades saw action movies held in more or less proper proportions, with action relegated to war movies, westerns, or the occasional spy thriller. John Wayne, William Holden, Steve McQueen, and Lee Marvin would preside over the action, usually playing men of few words. Then, the 1970s saw a shift towards existential dread as the rise of crime in cities allowed movies to tap into the audience’s fear of social unrest. (The plots of westerns and caper thrillers were too exotic to have any real-world connections. Vietnam had, for the moment, made the gung-ho heroics of war movies seem rather unseemly.) Movies like The French Connection, Dirty Harry, Death Wish, and various blaxploitation offerings gave us vigilante thrills and heroes that restored order in times of civil unrest. Guys like Clint Eastwood and Charles Bronson were older and still men of few words, but they were now providing comfort and safety.

But the ‘80s saw an accumulation of action movies, with a heavy emphasis on the flexing of one’s muscles. Cop buddy movies, urban vigilante movies, POW rescue movies, Chuck Norris karate movies, Death Wish sequels, you name it, dominated the theaters. The existential dread of the Watergate era had been replaced by Reagan-era optimism. Along with Eastwood, who had managed to become an elder statesman of action, Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger had become pillars of American might. The recurring image in ‘80s action movies was of an obscenely pumped-up one-man fighting machine. (It wasn’t a Stallone or Arnold movie until they were fighting the bad guys while wearing a tight t-shirt that accentuated their forearms.) Movies like Nighthawks, The Terminator, Rambo: First Blood Part II, Commando, Cobra, and The Running Man were outrageously entertaining comic-book depictions of outsized masculinity. But by summer ’88 audiences were starting to feel fatigued by all the car chases, shoot-outs, fistfights, and explosions. We kept going to action movies, but we were rarely surprised. That is, until one movie caught everyone by surprise and forever changed the language of the genre.

Die Hard was something new, an over-the-top blowout its director made personal by injecting humor and humanity into its incredible action set-pieces. Director John McTiernan staged the action with a you-are-there immediacy that was different from most other action movies. Your perspective was constantly shifting along with the hero’s, as if you yourself were always under the threat of attack. Die Hard was a ‘70s disaster movie crossed with a ‘80s one-man action vehicle, but it played like a witty character study.

And the character of John McClane turned out to be one of the most endearing action heroes in movie history. As played by Bruce Willis, McClane is a screw-up forced into action because bureaucracy and macho posturing are causing inaction. McClane is fully aware that he’s in way over his head. He sees the dark humor of his predicament which gives his one-liners a playful spontaneity. (“Come out to the coast, we’ll get together, have a few laughs!”) The casting of Willis in the lead was a masterstroke. We may now take for granted that TV actors can transition into movies, but back in 1988 it was a rare occurrence. (TV star Mark Harmon made a bid for action superstardom with the summer ’88 buddy thriller The Presidio, but he forgot to bring the humor.) On Moonlighting Willis played a smart-ass cut-up, but what made him instantly likable was the feeling that Willis himself was a smart-ass cut-up. In Blake Edwards’ comedies Blind Date and the criminally underrated Sunset, Willis displayed a knack for light slapstick and farce that, if you weren’t paying attention, could be seen as being one-dimensional. Willis always makes you aware that he knows he’s in the middle of an incredible situation. That’s what makes him such a compelling actor. (It’s also what makes him a star.) We want to see how Willis/John McClane (or Butch Coolidge in Pulp Fiction or Joe Hallenbeck in The Last Boy Scout or David Dunn in Unbreakable) gets out of a sticky situation. In Die Hard, Willis created a new action movie archetype: the everyman superhero.

The reason we root for McClane is because we know just how outmatched he truly is. As the villain Hans Gruber, Alan Rickman ushered in a new golden era of movie villains. With the exception of the Bond villains (who were just as dashing as Bond himself), the bad guys in movies were almost always secondary characters who rarely registered. (Anyone remember the name of Fernando Rey’s character in The French Connection?) The hero was the star, and stars can’t be upstaged. For the most part, memorable villains appeared only in exploitation movies (Vice Squad, 52 Pick-up) or intense psychological dramas (Manhunter, Blue Velvet). But Die Hard changed all that as the filmmakers realized the best way to make the hero look good is to put him up against someone stronger and in complete control. Previously, villains were the ones that sweated. Here, McClane’s undershirt is drenched in fear and desperation. Gruber is the ultimate villain for the 1980s: a sharp-dressed corporate raider who seizes the Nakatomi Corporation during its Christmas party in order to steal $640 million in negotiable bonds. Rickman infuses Gruber with such high comic levels of contempt and self-satisfaction that we’re genuinely startled when he turns violent. It’s a wickedly sinister performance, never more so than when he compliments Nakatomi president Takagi (James Shigeta) on his suit by flatly saying, “Nice suit. John Philips, London. I have two myself. Rumor has it Arafat buys his there.” Rickman makes being bad look good.

Die Hard looked and felt different from most other action movies. Shooting in widescreen allowed McTiernan to fill the frame with extra information about the Nakatomi building’s layout. Over the course of the movie, as McClane crawls through elevator shafts and ventilation ducts, we become familiar with recurring locations throughout the building. (McTiernan displayed a similar mastery of geography with the jungle-set Predator.) The cinematography by Jan de Bont (The Fourth Man) was quite daring for an action movie as he opted to pan on action instead of keeping the camera static. In an early scene, when one of the bad guys slides down a flight of stairs, the camera slides along with him. The many scenes of McClane running through empty offices and hallways have a thrilling sense of movement. By showing the building under construction, McTienran and De Bont could place fluorescent lights in the ground and have half-finished structures in the foreground. In one of my favorite sequences, as the LAPD S.W.A.T. team prepares a rescue attempt, we’re given several perspectives at once. There’s the computer expert Theo (Clarence Gilyard) watching the S.W.A.T. team get into position on a close-circuit monitor, while Hans looks down from an executive office. We also see McClane looking on helplessly as the police walk right into an ambush. (The climax of this sequence is one of the movie’s highlights.) The nearly non-stop score by Michael Kamen gives each set piece its own rhythm. At various points in the score Kamen incorporates Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy,” A playful acknowledgement that all an audience might want from a movie is to be thrilled.

There’s a distrust of authority and upper management running throughout Die Hard. The movie aligns itself with the working-class, be it funky limo driver Argyle (DeVoreaux White) or patrol officer Powell (Reginald VelJohnson). It’s when those in power arrive on the scene (S.W.A.T., the FBI, Deputy Chief Robinson) that ego begins to interfere with getting the job done. Of course McClane is a NYPD officer, but we quickly intuit that he doesn’t follow the rules. (Die Hard with a Vengeance begins with McClane on suspension.) This highlighting of the conflict between individual action and teamwork is really a variation on the ingrained conservative value system of action movies. John McClane is no different from Popeye Doyle, except we now cheer him on without reservation.

This conservative streak allows for some satirical riffing on alpha male action-movie heroics. Unlike his Planet Hollywood partners, Willis isn’t afraid to show a vulnerable side. In a brilliant touch that immediately makes McClane relatable, he spends the entire movie running around in his bare feet. We become acutely aware of the beating McClane is enduring, especially when he has to run across shards of broken glass. This is contrasted with the macho posturing of those in charge like blowhard Chief Robinson (Paul Gleason) and the borderline psychotic FBI agents who take over the negotiations. (During the rooftop climax, when the feds are manning a gunship, an agent exclaims, “Just like fuckin’ Saigon!”) Gruber is amused by alL the futile attempts to outsmart him and his men. At one point he asks McClane, “You know my name but who are you? Just another American who saw too many movies as a child? Another orphan of a bankrupt culture who thinks he’s John Wayne? Rambo? Marshal Dillon?” McClane’s response both mocks and pays respect to old-fashion American heroism.

It’s interesting to note that the summer of 1988 saw established action movie icons attempting to maintain their dominance. Stallone’s Rambo III was so by-the-numbers that even its title was tired. Schwarzenegger tried to make fun of his own image by doing the cop buddy action comedy Red Heat. In a symbolic changing-of-the-guard, Eastwood came out with the final Dirty Harry movie, the surprisingly entertaining The Dead Pool. But Die Hard set the template FOR all future action movies. The most immediate reflection of its impact was Hollywood’S attempt to copy its success with a series of “Die Hard on a …” movies. We got everything from “Die Hard on a submarine” (Under Siege) to “Die Hard on a plane” (Passenger 57) to “Die Hard on an island” (The Rock). (In the best Die Hard clone, Jan de Bont’s spectacular Speed, Keanu Reeves’ Jack Traven is the kind of guy who joined the LAPD because he saw Die Hard in theaters.) The movie’s more lasting impact is shown in the way it presented the hero, foregoing he-man stoicism in favor of intelligence and vulnerability. Die Hard gave us a hero with brains as well as muscles. You can see its influence in characters ranging from Batman to Jack Ryan to Ethan Hunt to Jason Bourne to James Bond (Daniel Craig’s take) to Jack Bauer. One of the movie’s taglines at the time claimed, “It will blow you though the back of the theater!” Boy, did it ever.

San Antonio-based film critic Aaron Aradillas is a contributor to The House Next Door, a contributor to Moving Image Source, and the host of “Back at Midnight,” an Internet radio program about film and television.

And newbie vamp Tara (Rutina Wesley) not only owning a surrogate mom in her maker Pam but a new BFF in Jessica (Deborah Ann Woll) courtesy an adorable scene—which you can watch above—where the latter waxes irresistable about sex, blood, morality, and how tough it is being a vamp, alone. Yes, there's a tiff over rights to Hoyt's neck, but for reals, these girls are made for each other: we just wonder how much . . .

And newbie vamp Tara (Rutina Wesley) not only owning a surrogate mom in her maker Pam but a new BFF in Jessica (Deborah Ann Woll) courtesy an adorable scene—which you can watch above—where the latter waxes irresistable about sex, blood, morality, and how tough it is being a vamp, alone. Yes, there's a tiff over rights to Hoyt's neck, but for reals, these girls are made for each other: we just wonder how much . . .

I've mentioned Rick

I've mentioned Rick

After Will’s epic on-air apology for falling down on the job, Don sits down to have a heart-to-heart with Jim, who has effectively replaced him. “I would have loved to be part of that. I could have done the show you guys want to do. I’m equipped for that,” he confesses. “You’ve got a mandate. Bring viewers to ten o’clock. I don’t . . . I have to cover Natalee Holloway. And you guys set me up to look like an asshole before I even got started.” Don is like Will, to a certain extent, a talented man who succumbed to the pressure to put on a show that was likable rather than substantive. But unlike Will, he’s relatively anonymous. He could be fired and Elliot’s show would keep ticking on without him. If Don is going to live in hopes of being able to make the kind of show that Jim and MacKenzie are making for Will, he has to keep his job. And that means kowtowing to a lot of unattractive people’s unattractive senses of what counts as news.

After Will’s epic on-air apology for falling down on the job, Don sits down to have a heart-to-heart with Jim, who has effectively replaced him. “I would have loved to be part of that. I could have done the show you guys want to do. I’m equipped for that,” he confesses. “You’ve got a mandate. Bring viewers to ten o’clock. I don’t . . . I have to cover Natalee Holloway. And you guys set me up to look like an asshole before I even got started.” Don is like Will, to a certain extent, a talented man who succumbed to the pressure to put on a show that was likable rather than substantive. But unlike Will, he’s relatively anonymous. He could be fired and Elliot’s show would keep ticking on without him. If Don is going to live in hopes of being able to make the kind of show that Jim and MacKenzie are making for Will, he has to keep his job. And that means kowtowing to a lot of unattractive people’s unattractive senses of what counts as news.

There’s the prepping of the MoMA space: the endless daily maddening minutiae of putting together a show that included approximately fifty works spanning over four decades of video works, installations, photographs, and collaborative performances made with ex-lover Ulay (Uwe Laysiepen).

There’s the prepping of the MoMA space: the endless daily maddening minutiae of putting together a show that included approximately fifty works spanning over four decades of video works, installations, photographs, and collaborative performances made with ex-lover Ulay (Uwe Laysiepen). Other works involved cutting her flesh, whipping herself, walking the Great Wall of China, and pushing her body to extreme limits of pain and suffocation. The Artist Is Present is eventually about the limits of human giving. If they exist.

Other works involved cutting her flesh, whipping herself, walking the Great Wall of China, and pushing her body to extreme limits of pain and suffocation. The Artist Is Present is eventually about the limits of human giving. If they exist.

With raffle drawings before each film, surprise screenings, and a plethora of special guests, the festival has become a staple of adventurous New York cinephiles' annual calendars. So while this

With raffle drawings before each film, surprise screenings, and a plethora of special guests, the festival has become a staple of adventurous New York cinephiles' annual calendars. So while this For example, Hong Kong filmmaker Edmond Pang has had a film screen at the festival before (Pang's Exodus screened in 2009). But this year, NYAFF will screen two of Pang's features and an eclectic shorts program called Pang Ho-Cheung's First Attempt. First Attempt was a one-time-only reprisal of an interactive experience where Pang talked about four of his early short films before, after and while they screened. Pang made these shorts with his mother and two brothers when he was 11, 12 and then 26 years old. The earlier shorts, where Pang improvised slow motion effects and spliced in footage from John Woo films like A Better Tomorrow

For example, Hong Kong filmmaker Edmond Pang has had a film screen at the festival before (Pang's Exodus screened in 2009). But this year, NYAFF will screen two of Pang's features and an eclectic shorts program called Pang Ho-Cheung's First Attempt. First Attempt was a one-time-only reprisal of an interactive experience where Pang talked about four of his early short films before, after and while they screened. Pang made these shorts with his mother and two brothers when he was 11, 12 and then 26 years old. The earlier shorts, where Pang improvised slow motion effects and spliced in footage from John Woo films like A Better Tomorrow And the festival hasn't stopped making new discoveries either. On Sunday, the festival screened The Sword Identity, the directorial debut of Chinese screenwriter/action choreographer Xu Haofeng. Haofeng is the screenwriter of The Grandmasters, Kar-wai Wong's upcoming martial arts epic. Watching The Sword Identity, you can easily see a similarity between Haofeng's interests and Wong's. Haofeng has made a genre film ideologically grounded in the notion that actions reflect character and that physical gestures and techniques always express the essence of things. That's the kind of story that the protagonists of both In the Mood for Love and 2046 dream of writing and the kind that Wong tried to make in Ashes of Time

And the festival hasn't stopped making new discoveries either. On Sunday, the festival screened The Sword Identity, the directorial debut of Chinese screenwriter/action choreographer Xu Haofeng. Haofeng is the screenwriter of The Grandmasters, Kar-wai Wong's upcoming martial arts epic. Watching The Sword Identity, you can easily see a similarity between Haofeng's interests and Wong's. Haofeng has made a genre film ideologically grounded in the notion that actions reflect character and that physical gestures and techniques always express the essence of things. That's the kind of story that the protagonists of both In the Mood for Love and 2046 dream of writing and the kind that Wong tried to make in Ashes of Time

“Dog Soldier” is built around the kidnapping—no murders this week, initially—of some Cheyenne boys who’ve been committed to foster care. There’s possible evidence of corruption in Social Services, of pedophilia, of corruption within the reservation, child abuse, or more. As the loose threads are connected or removed, the reasons for the kidnappings become more and more clear: the children were “kidnapped” in revenge for their removal, on false premises, from the reservation.

“Dog Soldier” is built around the kidnapping—no murders this week, initially—of some Cheyenne boys who’ve been committed to foster care. There’s possible evidence of corruption in Social Services, of pedophilia, of corruption within the reservation, child abuse, or more. As the loose threads are connected or removed, the reasons for the kidnappings become more and more clear: the children were “kidnapped” in revenge for their removal, on false premises, from the reservation.