My generation was ruined by Friends. The popular ‘90s sitcom, which recently celebrated the

My generation was ruined by Friends. The popular ‘90s sitcom, which recently celebrated the

20th anniversary of its premiere, flaunted vicious lies. It told us that, despite

our being undereducated, underemployed, and underwhelmed, we could have

beautiful apartments, plentiful leisure time, and love. I’m just entering my

late 30s, the same age that Ross, Chandler, Joey, Monica, Rachel, and Phoebe

would have reached at the show’s end, and I have neither a beautiful apartment,

nor leisure time, nor love. And worse, my expectations of those things, whether

by osmosis or by syndication (or both), have been manipulated and tempered by

the false hope embodied by the Central Perk 6 and the endless stream of

imitative sitcoms and romcoms that followed in Friends’ wake. FX’s You’re

the Worst is the antithesis of Friends,

an exploration of contemporary relationships that is fearless in its

dissemination of the futile and frustrating search for love.

The freshman sitcom from former Weeds and Orange is the New

Black writer Stephen Falk finished its first season last week, and here’s

hoping for the sake of the impressionable, helpless, loveless, spoiled

millennials who may have found this gem of a program that FX renews it for many

seasons to come. While Friends

placated a greedy generation while pandering to its flawed aspirations, You’re the Worst celebrates the flawed,

and panders to no one. The show is fiercely loyal to its rhetoric, finding

truth and honesty in the day-to-day frailties of its characters. You’re the Worst is a brilliant

re-imagining of the romantic sitcom, an exercise in using dark humour and

cynicism to provide a realistic and surprisingly hopeful outlook on life, while

eschewing the tropes of the genre, which made my generation cynical and

hopeless in life and love.

You’re the Worst

revolves around Jimmy Shive-Overly (Chris Geere) and Gretchen Cutler (Aya Cash);

two deeply wounded late 20-somethings who hook up at a common friend’s wedding.

Their first night together establishes both their selfish individualism and

rabid idiosyncrasies: He’s a failed novelist with a foot fetish. She’s a

publicist who once burned down her high school to avoid a math test. They are certainly

not the milquetoast insights of typical sitcom fare. Their expectation is that

they are indulging in a one-night stand, which breeds honesty in their pillow

talk. Yet somewhere in the twisted marginalia of their liaison, they find their

flaws bring them closer, and a romantic sitcom is born. Where once Ross and

Rachel’s will they/won’t they tied a generation to the deceit of Thursday

nights, Jimmy and Gretchen begin You’re

the Worst’s narrative arc by answering that question, and then they build a

show by endeavouring to sort through the painful minutiae involved in making a

relationship work.

The problem with the success of Friends (besides leading me to believe I could afford a Lower East

Side loft earning minimum wage) and the other seminal sitcoms of its era is

that it bred formulaic attempts at counterfeit programming. What resulted was

an endless supply of stock players who paled in comparison to the original

characters, and homogenized the medium. The wacky neighbour, the sarcastic best

friend, the couple with it all, the manic pixie dream girl. In a commentary on,

and indictment of, these archetypes, You’re

the Worst manages to both include and defy these trope characters beyond

its leads. The wacky neighbour (Killian) is a lonely kid (Shane Francis Smith).

The sarcastic best friend (Edgar) is a war vet with PTSD (the excellent Desmin

Borges). The perfect couple (Lindsay and Paul) is anything but (the equally

excellent Kether Donohue and Allan McLeod). And the manic pixie dream girl

(Cash’s Gretchen) is… well, okay, some things never change. However, You’re the Worst dares its audience to

indulge not in laughing at the comically flawed as did its sitcom ancestors,

but the comedy of the flawed, which is far more honest and infinitely more

entertaining.

At the core of the show is the relationship between Jimmy

and Gretchen, and the brilliant twisted chemistry between Geere and Cash. While

sitcoms like Friends operate under

the false understanding that love and its consummation is impossible yet oddly

inevitable, You’re the Worst contends

that consummation and love are easy, but breakups and heartbreak are

inevitable. In the show’s first season’s finale, the two main paramours end up

moving in together. Not because they love each other, which they might. Not

because it makes sense financially, which it could. And not because the

audience demands it. Rather because Gretchen sets fire to her apartment with a

poorly maintained vibrator. That never happened to Rachel. But the truth

remains that life is more often dictated by happenstance that shapes important

decisions, as opposed to grandiose and theatrical declarations. In the pounding

rain. With Coldplay playing.

Beyond discussion of love and a distain for archetypes, You’re the Worst finds delight in the

notion that people are quite simply fucked up. Television typically treats us

to caricatures of the wounded, clowns for our amusement, monkeys who dance for

twenty-two minutes a week, twenty-six times a year, and infinitely into the

abyss of syndication. For those of us

all too aware of our flaws, our struggles, our shortcomings, these characters

are insulting, because they demean our reality. You’re the Worst manages to gratify itself in the blemished

weaknesses of its characters, and in doing so satisfies the audience’s need for

empathy. Jimmy is a narcissist and coming to terms with the limitations of his talents.

Gretchen is a drug-addled slob, a barely competent adult. Lindsay is an

adulterer in a quietly broken marriage. Everybody is promiscuous. And in

contrast to the tired sitcom fare we’ve been drowned by, yet asked to aspire to

for twenty years, in truth many people are promiscuous, narcissistic,

drug-addled, barely competent adults coming to terms with the limits of our

talents. Yet in You’re the Worst, the

fucked-up are not exploited as caricatures, as television is wont to do. They’re

simply presented as average. And within the comfort of that acceptance, the

vindication of normality is the essence of the show’s ability to find humour in

our flaws.

As the finale makes its way to its conclusion, the central

couple are startled by the decision to cohabitate. Gretchen looks at Jimmy, and

with hesitatant affection, she says, “We’re gonna do this even though we know

there is only one way this ends. Whether in a week or twenty years there is

horrible sadness and pain coming and we’re inviting it.” There is a powerful

and beautiful honesty in that declaration, a vicious truth that is rarely found

in television, let alone a sitcom. And yet, they’re willing to try. The sad

inevitability of their end demands that the audience follows them to their

demise. But not with trepidation or worry, but with understanding and empathy.

Because for most of us, the inevitable end is the norm, whether in learned

truth or cynical expectation, and the route there is all we have. To find

humour in that commonality is comforting, and that is what makes You’re the Worst the most engaging

exploration of relationships within the sitcom genre in recent memory. In fact,

there may have never been a more honest examination of the history and mythology

of a relationship on television before.

For the first time in U.S. history, single people (16 and

over) are the majority, according to data used by the Bureau of Labor

Statistics. And while television loves to exploit the lives of the unattached,

it has always done so with the understanding that true love is an impending

determinant, that eccentricity is a phase, that the flawed can be fixed. You’re the Worst revels in the majesty

of eccentricity and flaw, and argues that heartbreak is inevitable, and yet

indulges wonderfully in the narrative of the attempt to settle that argument. Like

relationships, we never really know when a sitcom will end. As a result, the

norm has been to couple and uncouple characters until the audience, or the

network, has seen enough. In You’re the

Worst, we’re being treated to a truly prodigious employment of the sitcom

and the device of love. I just hope FX allows us to continue to indulge in its

journey.

Mike Spry is a writer, editor, and columnist who has written for The

Toronto Star, Maisonneuve, and The Smoking Jacket, among

others, and contributes to MTV’s PLAY

with AJ. He is the author of the poetry collection JACK (Snare

Books, 2008) and Bourbon & Eventide (Invisible Publishing, 2014), the short story collection Distillery Songs (Insomniac Press,

2011), and the co-author of Cheap Throat: The Diary of a Locked-Out

Hockey Player (Found Press,

2013). Follow him on Twitter @mdspry.

The latest series from director Steven Soderbergh begins

The latest series from director Steven Soderbergh begins

Humor can be the cut and the balm—sometimes

Humor can be the cut and the balm—sometimes

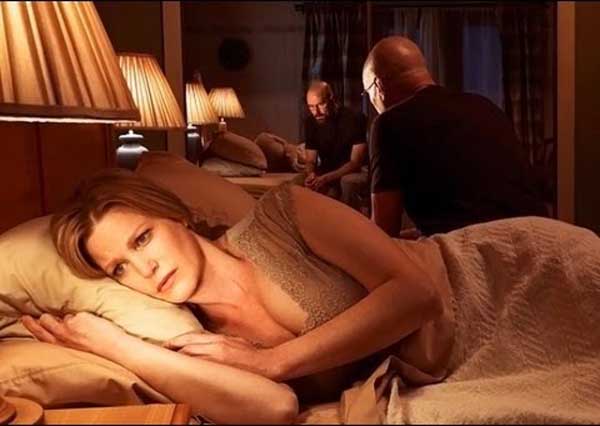

In episode “Fifty-One” of Breaking

In episode “Fifty-One” of Breaking

What do you consider offensive? The dictionary definition of

What do you consider offensive? The dictionary definition of