[Editor's note: Tuco Salamanca's twin cousins Marco and Leonel were among the most fascinating characters on Breaking Bad. Stoic, menacing and quietly murderous, they were quickly established as a force to be reckoned with. We wondered: If we were to reorder each of their scenes from Breaking Bad's third season into a chronology, would their story be as compelling? Would it be different entirely? Could we glean greater insight into these two men?

We asked Press Play contributor Dave Bunting, Jr. to edit these scenes together (in addition to the prologues of all four seasons to create two self-contained Breaking Bad episodes, one covering Seasons 1 and 2, the other covering Seasons 3 and 4.) He arranged all of The Cousins' material in chronological order except for a late-season flashback to their childhood, which he placed at the start. Then we asked another Press Play contributor, Sheila O'Malley — who has never seen a frame of the series — to watch the compilation and write down her impressions. Sheila was asked not to read any supplementary material before or during the experiment, and she agreed. Her written account of The Cousins is derived entirely from having watched Dave's compilations. Shorn of everything but its openings, was Breaking Bad still Breaking Bad? Read on and see.]

The two boys were inseparable growing up. They were twins, and although they fought on occasion, there was a special unbreakable bond between them at all times. Words were rarely necessary. They would just look at each other and know what the other one was thinking. It was a psychological and intellectual bond, bordering on the spiritual. It is a profound thing to not need words. Nobody else could enter their cyclical closed bond. That was okay by them. As long as they had each other, they didn't need anyone else.

There is always a moment in life when your character is determined. It usually happens early. And character can mean destiny. All else follows from that one moment; it is as though it was written in the stars.

Something happened when they were young that was crucial to the development of their characters as men. They were about 10 years old, and playing in the yard, as their uncle looked on, talking on a giant phone the size of a computer modem. Their uncle was a bigwig in the family drug cartel, a behemoth with many tentacles, reaching into the United States. He was running his business from a lawn chair, as the boys played and taunted one another. To the boys, their lives were normal, of course. They didn't know that their lives were any different than anyone else's. One boy takes the other's G.I. Joe doll and holds it just out of reach, taunting his brother until his brother breaks into tears, shouting, "I wish you were dead!" This innocent comment gets the uncle's attention. He calls both boys over, taking in the situation wordlessly and then asks the boy who had taunted his brother to get him a beer out of the bucket of melting ice beside his chair. The little boy reaches in, grabs a beer and holds it out but the uncle rejects it, telling him to get him one that is really cold. Leaning over the bucket, reaching in deeper, the little boy is caught unaware when the uncle swiftly pushes his head beneath the water. A struggle ensues. The uncle remains imperturbable, and asks the boy standing in front of him, "This is what you wanted, right?" The panic of the boy being held under the water intensifies, and his brother, desperate, starts hitting his uncle ferociously. Just before the submerged boy would have drowned, the uncle lets him go, and the boys huddle together by the bucket. The uncle stares down at the boys and says, "Family is all."

Something happened when they were young that was crucial to the development of their characters as men. They were about 10 years old, and playing in the yard, as their uncle looked on, talking on a giant phone the size of a computer modem. Their uncle was a bigwig in the family drug cartel, a behemoth with many tentacles, reaching into the United States. He was running his business from a lawn chair, as the boys played and taunted one another. To the boys, their lives were normal, of course. They didn't know that their lives were any different than anyone else's. One boy takes the other's G.I. Joe doll and holds it just out of reach, taunting his brother until his brother breaks into tears, shouting, "I wish you were dead!" This innocent comment gets the uncle's attention. He calls both boys over, taking in the situation wordlessly and then asks the boy who had taunted his brother to get him a beer out of the bucket of melting ice beside his chair. The little boy reaches in, grabs a beer and holds it out but the uncle rejects it, telling him to get him one that is really cold. Leaning over the bucket, reaching in deeper, the little boy is caught unaware when the uncle swiftly pushes his head beneath the water. A struggle ensues. The uncle remains imperturbable, and asks the boy standing in front of him, "This is what you wanted, right?" The panic of the boy being held under the water intensifies, and his brother, desperate, starts hitting his uncle ferociously. Just before the submerged boy would have drowned, the uncle lets him go, and the boys huddle together by the bucket. The uncle stares down at the boys and says, "Family is all."

In that moment is the destiny of these beautiful boys. It would be a scar, of course. Their uncle was willing to kill one of them to teach them both a lesson. They would never feel the same way about him again. However, the lesson was learned. Family is all, and to wish death upon a family member is forbidden. In the ensuing years, as they grew older, they mind-melded to such a degree that they became one larger impenetrable entity. They were not two individuals. They had coalesced into a terrifying Third.

As teenagers, they began working for the family business. While their uncle was a negotiator, the twins were the muscle. They killed enemies of the family with a breathtaking swiftness. They were perfectly suited, emotionally, for the job. They didn't experience an adrenaline rush like normal people in the face of danger. On the contrary, when faced with a dangerous situation, their blood pressure lowered. They were able to be very still. They had patience, they could wait. They had a deep coiled core of rage inside them, but their faces remained placid and flat. They liked to kill people with axes. Sure, you could shoot someone, but it wasn't as satisfying. They felt nothing as they chopped off the head of a man in the back room of a bar. He screamed, of course, but that didn't matter. They all scream.

As teenagers, they began working for the family business. While their uncle was a negotiator, the twins were the muscle. They killed enemies of the family with a breathtaking swiftness. They were perfectly suited, emotionally, for the job. They didn't experience an adrenaline rush like normal people in the face of danger. On the contrary, when faced with a dangerous situation, their blood pressure lowered. They were able to be very still. They had patience, they could wait. They had a deep coiled core of rage inside them, but their faces remained placid and flat. They liked to kill people with axes. Sure, you could shoot someone, but it wasn't as satisfying. They felt nothing as they chopped off the head of a man in the back room of a bar. He screamed, of course, but that didn't matter. They all scream.

Genetics had favored the boys with beautiful movie-star good looks. They both shaved their heads. They preferred to dress in silk suits, monochromatic and flashy. Maybe they had seen some <i>Miami Vice</i> episodes as kids. They were vain. They were constantly having to change clothes, due to the blood splatter of their victims, and they were always on the lookout for a clothesline. They wore stunning custom-made cowboy boots, with an upturned lip featuring a leering skull. It was their trademark.

By the time they reached adulthood, the boys had settled into a routine, and had no need for language at all anymore. Their movements remained calculated and yet almost casual. Normal people experience tension from time to time, especially in stressful situations. The twins rarely betray tension. Indeed, they rarely experience tension at all. Instead, what they seem to experience, on almost a cellular level, is that there is unfinished business out there, and they will not rest until the scales have been righted.

After their cousin Tuco is betrayed by some meth guy in Albuquerque named "Walter White", the twins know what they have to do. They move forward inexorably, getting closer and closer to their target. In a makeshift shrine devoted to death and their enemies, they place a sketch of "Walter White" beside a skull. Gleaming in their silver suits, they stare at the sketch, glance at one another, and then stare back. They have him in their sights, like a hungry lion spotting a lame antelope, and waiting, patiently, until the time is right to pounce.

After their cousin Tuco is betrayed by some meth guy in Albuquerque named "Walter White", the twins know what they have to do. They move forward inexorably, getting closer and closer to their target. In a makeshift shrine devoted to death and their enemies, they place a sketch of "Walter White" beside a skull. Gleaming in their silver suits, they stare at the sketch, glance at one another, and then stare back. They have him in their sights, like a hungry lion spotting a lame antelope, and waiting, patiently, until the time is right to pounce.

Occasionally, regular people have interactions with the twins. And, without fail, the regular person will make eye contact, and immediately sense that something is "off", and draw back in confusion and revulsion. The twins are used to social rejection on that level. They know they aren't like other people. They wouldn't want to be like other people, screaming and whining just before death, and laughing about stupid things, and talking about nothing. Regular people are so undignified. They are bored by everything.

Their difference is acknowledged by the cartel representative himself during a negotiating moment with a meth supplier in the Albuquerque area. The cartel has come to the supplier to explain that the twins need to exact revenge for the betrayal of their cousin. The supplier politely says that he needs Walter White alive, he is working with the man and White is crucial to his business. Pulling the supplier aside, the cartel rep says, "I totally understand. But you have to understand that the boys might not be able to wait." He then says, pausing, as he tries to find the words, "These boys …. are not like you and I."

Even hardened criminals recognize that these boys are different.

In their pursuit of Walter White, they remain unflappable. One day, they walk into White's house, holding their favorite axe, polished to a highly reflective gleam. White is singing in the shower. The boys, betraying no nervousness that they are in someone else's house, stroll casually through the rooms, checking out the pictures on the fridge, glancing at one another for eloquent moments of silent conversation. They sit on the bed, waiting for Walter to come out. Their faces are the blank faces of a cobra, just before it strikes. All the energy and desire inside of them has poured itself into a tiny container, with no escape valve until the axe falls. At the last minute, they are called off the job by an urgent text from the cartel, and, with White just emerging from the shower, the twins get up and leave the house.

They have been told that Walter White is off limits. This is one of the only times that their beautiful faces betray any emotion. They look stopped up with annoyance, but more than annoyance, they are truly baffled that someone has the balls to say "No" to them. It does not compute. Their brains are set up on a very simple wiring system, and their impulses flow naturally from thought and vice versa. There is no need to analyze any of it. When there is unfinished business, you handle it.

The meth supplier, realizing that he is in a world of trouble by saying "No" to the twins, sets up a private meeting with them in a vacant field outside of town. He acknowledges their family feeling and he acknowledges their need for revenge, but Walter White needs to stay alive. However, he must remind the twins that Walter White did not actually pull the trigger on the gun that killed their cousin. That job was done by White's brother-in-law, who was a DEA agent. One of the twins says, "We were told the DEA was off-limits." It is rare to hear either of them speak. The meth supplier assures them that this is his territory, and he calls the shots here. Go kill the DEA agent if that is what you need to do.

The meth supplier, realizing that he is in a world of trouble by saying "No" to the twins, sets up a private meeting with them in a vacant field outside of town. He acknowledges their family feeling and he acknowledges their need for revenge, but Walter White needs to stay alive. However, he must remind the twins that Walter White did not actually pull the trigger on the gun that killed their cousin. That job was done by White's brother-in-law, who was a DEA agent. One of the twins says, "We were told the DEA was off-limits." It is rare to hear either of them speak. The meth supplier assures them that this is his territory, and he calls the shots here. Go kill the DEA agent if that is what you need to do.

The scene ends with the supplier saying to them, realizing that he is in the presence of something completely "other" and not altogether human, "I hope his death will be satisfying to you."

In the shootout that follows, things do not go according to plan. They stalk the DEA agent to his car in the parking lot of a mall. The DEA agent has been tipped off by an anonymous phone call that two people are coming to kill him right now, he has 5 minutes left. While the DEA agent looks around the parking lot, palpably terrified, he sees nothing. Until, from out of nowhere, in gleaming silver and white suits, the twins appear. One shoots through the window. The DEA agent has been shot but still puts the car in reverse and slams on the gas, crushing one of the twins between his car and the one behind him. The DEA agent crawls out of his vehicle, and the crushed twin is released, falling to the pavement.

Here we finally see how character is destiny. The uninjured twin, thrown off his game for the first time, runs to his fallen brother. It is already inconceivable to him how he will live without the other. It's not just that he is a half-person without his brother. He is nothing at all, and will implode completely. The fallen brother, in agony, says up to his twin, "Finish him."

It is the final request of the only person he has ever loved, and is the fulfillment of the prophecy of the uncle many years before when they were boys on that fateful day. "Family is all."

And while he may finish off the DEA agent, for the first time he is rattled enough to make an error, a deadly mental error. The person finished off here will be him.

Sheila O'Malley is a film critic for Capital New York. She blogs about film, television, theater, music, literature and pretty much everything else at The Sheila Variations.

Dave Bunting, Jr. is a writer, musician and audio engineer, and a frequent narrator of videos for Press Play, The L Magazine and TomatoNation.

A lack of positive ethnic representation in cinema forced Cuban Americans like myself to adopt Scarface and its Cuban drug-lord Tony Montana into our cultural iconography (which I talk about at length

A lack of positive ethnic representation in cinema forced Cuban Americans like myself to adopt Scarface and its Cuban drug-lord Tony Montana into our cultural iconography (which I talk about at length

The subjects and characters that Korine presents exist outside the mainstream frame of heroes or villains. The silver screen heroines of Hollywood are now replaced with the rebellious, foul-mouthed street teens in Act Da Fool. The team of charming casino robbers or frontier-bound cowboys is now replaced with the outcast garbage can fornicators in Trash Humpers. By stripping away any safe scenario that would be found in a typical "movie," Korine forces the audience to reevaluate their primal reactions to some of the most obtuse and harrowing images. Therefore, these films transcend the visual mechanics behind the “normal” American narrative. Added, the locations that Korine uses for these films–decrepit housing, low-income neighborhoods–represent an underexposed cross-section of very real America (when compared to popular Hollywood content).

The subjects and characters that Korine presents exist outside the mainstream frame of heroes or villains. The silver screen heroines of Hollywood are now replaced with the rebellious, foul-mouthed street teens in Act Da Fool. The team of charming casino robbers or frontier-bound cowboys is now replaced with the outcast garbage can fornicators in Trash Humpers. By stripping away any safe scenario that would be found in a typical "movie," Korine forces the audience to reevaluate their primal reactions to some of the most obtuse and harrowing images. Therefore, these films transcend the visual mechanics behind the “normal” American narrative. Added, the locations that Korine uses for these films–decrepit housing, low-income neighborhoods–represent an underexposed cross-section of very real America (when compared to popular Hollywood content).

Something happened when they were young that was crucial to the development of their characters as men. They were about 10 years old, and playing in the yard, as their uncle looked on, talking on a giant phone the size of a computer modem. Their uncle was a bigwig in the family drug cartel, a behemoth with many tentacles, reaching into the United States. He was running his business from a lawn chair, as the boys played and taunted one another. To the boys, their lives were normal, of course. They didn't know that their lives were any different than anyone else's. One boy takes the other's G.I. Joe doll and holds it just out of reach, taunting his brother until his brother breaks into tears, shouting, "I wish you were dead!" This innocent comment gets the uncle's attention. He calls both boys over, taking in the situation wordlessly and then asks the boy who had taunted his brother to get him a beer out of the bucket of melting ice beside his chair. The little boy reaches in, grabs a beer and holds it out but the uncle rejects it, telling him to get him one that is really cold. Leaning over the bucket, reaching in deeper, the little boy is caught unaware when the uncle swiftly pushes his head beneath the water. A struggle ensues. The uncle remains imperturbable, and asks the boy standing in front of him, "This is what you wanted, right?" The panic of the boy being held under the water intensifies, and his brother, desperate, starts hitting his uncle ferociously. Just before the submerged boy would have drowned, the uncle lets him go, and the boys huddle together by the bucket. The uncle stares down at the boys and says, "Family is all."

Something happened when they were young that was crucial to the development of their characters as men. They were about 10 years old, and playing in the yard, as their uncle looked on, talking on a giant phone the size of a computer modem. Their uncle was a bigwig in the family drug cartel, a behemoth with many tentacles, reaching into the United States. He was running his business from a lawn chair, as the boys played and taunted one another. To the boys, their lives were normal, of course. They didn't know that their lives were any different than anyone else's. One boy takes the other's G.I. Joe doll and holds it just out of reach, taunting his brother until his brother breaks into tears, shouting, "I wish you were dead!" This innocent comment gets the uncle's attention. He calls both boys over, taking in the situation wordlessly and then asks the boy who had taunted his brother to get him a beer out of the bucket of melting ice beside his chair. The little boy reaches in, grabs a beer and holds it out but the uncle rejects it, telling him to get him one that is really cold. Leaning over the bucket, reaching in deeper, the little boy is caught unaware when the uncle swiftly pushes his head beneath the water. A struggle ensues. The uncle remains imperturbable, and asks the boy standing in front of him, "This is what you wanted, right?" The panic of the boy being held under the water intensifies, and his brother, desperate, starts hitting his uncle ferociously. Just before the submerged boy would have drowned, the uncle lets him go, and the boys huddle together by the bucket. The uncle stares down at the boys and says, "Family is all." As teenagers, they began working for the family business. While their uncle was a negotiator, the twins were the muscle. They killed enemies of the family with a breathtaking swiftness. They were perfectly suited, emotionally, for the job. They didn't experience an adrenaline rush like normal people in the face of danger. On the contrary, when faced with a dangerous situation, their blood pressure lowered. They were able to be very still. They had patience, they could wait. They had a deep coiled core of rage inside them, but their faces remained placid and flat. They liked to kill people with axes. Sure, you could shoot someone, but it wasn't as satisfying. They felt nothing as they chopped off the head of a man in the back room of a bar. He screamed, of course, but that didn't matter. They all scream.

As teenagers, they began working for the family business. While their uncle was a negotiator, the twins were the muscle. They killed enemies of the family with a breathtaking swiftness. They were perfectly suited, emotionally, for the job. They didn't experience an adrenaline rush like normal people in the face of danger. On the contrary, when faced with a dangerous situation, their blood pressure lowered. They were able to be very still. They had patience, they could wait. They had a deep coiled core of rage inside them, but their faces remained placid and flat. They liked to kill people with axes. Sure, you could shoot someone, but it wasn't as satisfying. They felt nothing as they chopped off the head of a man in the back room of a bar. He screamed, of course, but that didn't matter. They all scream. After their cousin Tuco is betrayed by some meth guy in Albuquerque named "Walter White", the twins know what they have to do. They move forward inexorably, getting closer and closer to their target. In a makeshift shrine devoted to death and their enemies, they place a sketch of "Walter White" beside a skull. Gleaming in their silver suits, they stare at the sketch, glance at one another, and then stare back. They have him in their sights, like a hungry lion spotting a lame antelope, and waiting, patiently, until the time is right to pounce.

After their cousin Tuco is betrayed by some meth guy in Albuquerque named "Walter White", the twins know what they have to do. They move forward inexorably, getting closer and closer to their target. In a makeshift shrine devoted to death and their enemies, they place a sketch of "Walter White" beside a skull. Gleaming in their silver suits, they stare at the sketch, glance at one another, and then stare back. They have him in their sights, like a hungry lion spotting a lame antelope, and waiting, patiently, until the time is right to pounce. The meth supplier, realizing that he is in a world of trouble by saying "No" to the twins, sets up a private meeting with them in a vacant field outside of town. He acknowledges their family feeling and he acknowledges their need for revenge, but Walter White needs to stay alive. However, he must remind the twins that Walter White did not actually pull the trigger on the gun that killed their cousin. That job was done by White's brother-in-law, who was a DEA agent. One of the twins says, "We were told the DEA was off-limits." It is rare to hear either of them speak. The meth supplier assures them that this is his territory, and he calls the shots here. Go kill the DEA agent if that is what you need to do.

The meth supplier, realizing that he is in a world of trouble by saying "No" to the twins, sets up a private meeting with them in a vacant field outside of town. He acknowledges their family feeling and he acknowledges their need for revenge, but Walter White needs to stay alive. However, he must remind the twins that Walter White did not actually pull the trigger on the gun that killed their cousin. That job was done by White's brother-in-law, who was a DEA agent. One of the twins says, "We were told the DEA was off-limits." It is rare to hear either of them speak. The meth supplier assures them that this is his territory, and he calls the shots here. Go kill the DEA agent if that is what you need to do.

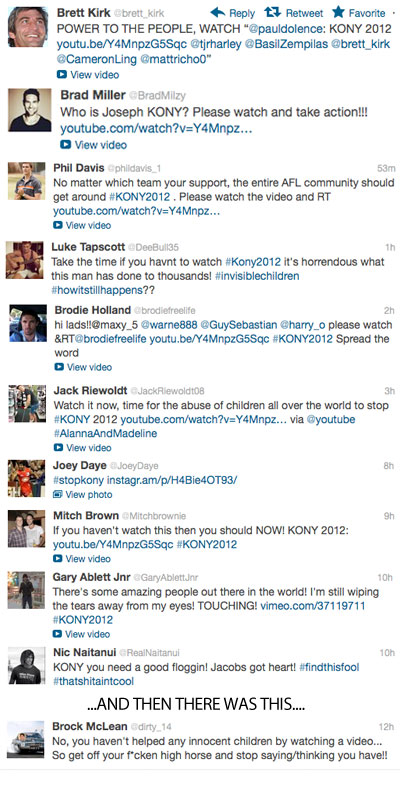

The video is a staggering viral sensation, at this point having been viewed over 70 million times on YouTube, but the conversation it has spurred has been, unsurprisingly, repetitive and stagnant. Kony 2012 is the latest example of a public discourse caught in a cycle of perpetual feedback, from thesis to antithesis. But rarely do we arrive at synthesis. Rather arguments spur counter arguments, which only return to the same arguments, around and around, in what only looks like motion but is actually stasis.

The video is a staggering viral sensation, at this point having been viewed over 70 million times on YouTube, but the conversation it has spurred has been, unsurprisingly, repetitive and stagnant. Kony 2012 is the latest example of a public discourse caught in a cycle of perpetual feedback, from thesis to antithesis. But rarely do we arrive at synthesis. Rather arguments spur counter arguments, which only return to the same arguments, around and around, in what only looks like motion but is actually stasis. There is nothing particularly controversial about calling Joseph Kony a monster. For 25 years, Kony and the LRA, a militant offshoot of other Acholi-nationalist movements in northern Uganda, have survived the tribal insurrections of the late 1980s due to the unwavering fanaticism of its leader and his willingness to commit the most brutal of atrocities. The LRA is sponsored by no government, and adheres to no pre-fab revolutionary ideology; its cult is strictly of Kony’s personality, which blends tribalism with a mystical Christianity (he believes in the literal protective power of crucifixes and holy water). Joseph Kony is not a genocidal dictator, he is a fanatical strongman who has carved out his fiefdom the way fanatical strongmen always have, with unrelenting barbarism.

There is nothing particularly controversial about calling Joseph Kony a monster. For 25 years, Kony and the LRA, a militant offshoot of other Acholi-nationalist movements in northern Uganda, have survived the tribal insurrections of the late 1980s due to the unwavering fanaticism of its leader and his willingness to commit the most brutal of atrocities. The LRA is sponsored by no government, and adheres to no pre-fab revolutionary ideology; its cult is strictly of Kony’s personality, which blends tribalism with a mystical Christianity (he believes in the literal protective power of crucifixes and holy water). Joseph Kony is not a genocidal dictator, he is a fanatical strongman who has carved out his fiefdom the way fanatical strongmen always have, with unrelenting barbarism.

At its heart, the Kony 2012 is a naïve-yet-earnest plea for justice to be done, which accounts, at least in part, for its popularity, which is. While that earnestness does not have to be shared, it should not be dismissed either. Justice is an abstract concept, and we should all want more concrete ways to measure it. Kony seems like a clear-cut case where justice could be served by his capture and prosecution, but how can we be expected to have productive conversation about justice when our institutional instruments are being bent to justify acceptable body counts for extra-legal operations? Our standards for justice in our discourse have been warped, stunting our ability to take meaningful actions based on what is right and wrong in the greater world.

At its heart, the Kony 2012 is a naïve-yet-earnest plea for justice to be done, which accounts, at least in part, for its popularity, which is. While that earnestness does not have to be shared, it should not be dismissed either. Justice is an abstract concept, and we should all want more concrete ways to measure it. Kony seems like a clear-cut case where justice could be served by his capture and prosecution, but how can we be expected to have productive conversation about justice when our institutional instruments are being bent to justify acceptable body counts for extra-legal operations? Our standards for justice in our discourse have been warped, stunting our ability to take meaningful actions based on what is right and wrong in the greater world.

Season 3 opens with a surreal scene of a group of people crawling in the dirt through a rustic Mexican village. It seems that some well-known ritual is taking place. Nobody seems too surprised at the sight. A gleaming car pulls up and two men get out. They are bald, handsome, and dressed in immaculate suits. They are also identical twins. Without hesitation, they join the ritual, lying down in the dirt, despite their silk suits, and crawling along with the others. The destination is a run-down shack which has been built into some kind of shrine. Inside there are lit candles with dripping wax and bouquets and skulls draped in beads. The men in suits pin a picture up on the wall. It is a sketch of the chemistry teacher. Wherever we are in this opening scene is far from the sun-blasted streets of Albuquerque (the stomping grounds of the chemistry teacher), but it is clear that his fearsome influence is spreading.

Season 3 opens with a surreal scene of a group of people crawling in the dirt through a rustic Mexican village. It seems that some well-known ritual is taking place. Nobody seems too surprised at the sight. A gleaming car pulls up and two men get out. They are bald, handsome, and dressed in immaculate suits. They are also identical twins. Without hesitation, they join the ritual, lying down in the dirt, despite their silk suits, and crawling along with the others. The destination is a run-down shack which has been built into some kind of shrine. Inside there are lit candles with dripping wax and bouquets and skulls draped in beads. The men in suits pin a picture up on the wall. It is a sketch of the chemistry teacher. Wherever we are in this opening scene is far from the sun-blasted streets of Albuquerque (the stomping grounds of the chemistry teacher), but it is clear that his fearsome influence is spreading. This young man lives in isolation in a ratty room, spending most of his time playing violent video games, imagining his real-life enemies before him. He dates a pretty young woman, who takes him to a Georgia O'Keefe exhibit. He is singularly unimpressed, staring at one of O'Keefe's famous flower paintings and declaring, "That doesn't look like any vagina I ever saw." In the car afterwards, they talk about art, and repetition, and she tries to tell him what he is missing in his interpretaion of O'Keefe's work. In this scene he is almost fresh-faced. He kisses her gently. You really see how far this kid has fallen when you consider that in most other scenes he is either jacked up on meth, buying gas he can't pay for and then trading drugs with the cashier to pay for it, or beaten almost beyond recognition. There is a slow steady progression into hell with this character, and leaping around in time nails that point home.

This young man lives in isolation in a ratty room, spending most of his time playing violent video games, imagining his real-life enemies before him. He dates a pretty young woman, who takes him to a Georgia O'Keefe exhibit. He is singularly unimpressed, staring at one of O'Keefe's famous flower paintings and declaring, "That doesn't look like any vagina I ever saw." In the car afterwards, they talk about art, and repetition, and she tries to tell him what he is missing in his interpretaion of O'Keefe's work. In this scene he is almost fresh-faced. He kisses her gently. You really see how far this kid has fallen when you consider that in most other scenes he is either jacked up on meth, buying gas he can't pay for and then trading drugs with the cashier to pay for it, or beaten almost beyond recognition. There is a slow steady progression into hell with this character, and leaping around in time nails that point home. Seasons 3 and 4 also deal heavily with the chemistry aspect of meth production (which is a propos seeing as how the opening credits sequence features a periodic table), as well as the ins and outs of running a successful drug dealing business. A local Mexican restaurant in Albuquerque called Los Pollos Hermanos is a front, and freezer trucks filled with crystals hurtle across the desert, with armed men crouched in the back, their breath showing in the cold darkness. Often these trucks are stopped by rival drug-dealers. Multiple shoot-outs occur. We also see the creation of the meth itself, characters in white suits and gloves moving the gleaming blue crystals along, bagging them up. Later, we learn that this particular brand of meth is 99% pure, and industry-standard appears to be around 96%. Others wonder what the secret is, how this meth can be so pure, and how it is done. That 3% gap in quality serves to "up" other people's games.

Seasons 3 and 4 also deal heavily with the chemistry aspect of meth production (which is a propos seeing as how the opening credits sequence features a periodic table), as well as the ins and outs of running a successful drug dealing business. A local Mexican restaurant in Albuquerque called Los Pollos Hermanos is a front, and freezer trucks filled with crystals hurtle across the desert, with armed men crouched in the back, their breath showing in the cold darkness. Often these trucks are stopped by rival drug-dealers. Multiple shoot-outs occur. We also see the creation of the meth itself, characters in white suits and gloves moving the gleaming blue crystals along, bagging them up. Later, we learn that this particular brand of meth is 99% pure, and industry-standard appears to be around 96%. Others wonder what the secret is, how this meth can be so pure, and how it is done. That 3% gap in quality serves to "up" other people's games. But the chemistry teacher has been living in two worlds for too long. As Season 4 progresses, that separation becomes harder and harder to maintain

But the chemistry teacher has been living in two worlds for too long. As Season 4 progresses, that separation becomes harder and harder to maintain