Billionaire business mogul Eric Packer (Robert Pattinson) treats his body like a temple, receiving a health assessment from a physician every day like clockwork. One such appraisal takes place midway through Cosmopolis, David Cronenberg’s talky and occasionally scathing post-modern nightmare about the downfall of capitalism in the modern age. This gnarly doctor’s visit includes a brutally frank rectal exam that becomes highly erotic for both Eric and a female colleague standing inches away.

The physical body and all its beautiful horrors have long been essential to Cronenberg, but in Cosmopolis they become a way station for penetrating absurdities and diseased ideas. Lengthy dialogue-driven sequences, most taking place between Eric and various lovers, employees, and business advisors inside his brilliantly white high-tech stretch limousine, explore the way we construct fantasy and gather data to justify our hollowed-out existences. If Eric’s descent into the heart of darkness is any indication, we’ve failed.

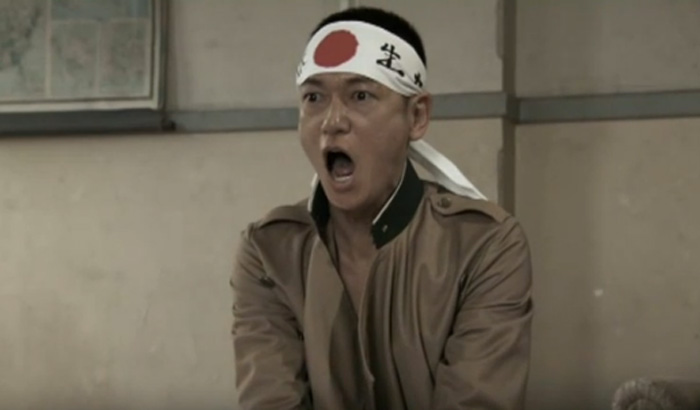

Adapted from Don DeLillo’s famous novel, Cosmopolis faithfully follows Eric on a long and slow jaunt across Manhattan to get a haircut. Multiple complications threaten to compromise his trip, including a visit from the U.S. President and the funeral for a famous rap star. During his Ulysses-like journey, Eric’s professional and physical worlds quickly collapse, revealing the ideological rot and deformation of his soul that has been repressed underneath a mountain of wealth. Constantly questioning and forever yearning, Eric is the ultimate empty vessel trying to reclaim something, anything in the way of an identity.

But it’s not just Eric’s existence that seems on the verge of self-immolation: the entire city is tipping into the void. Angry protesters spray-paint Eric’s limo during a heated battled with riot police, screaming “A specter is haunting” while flinging dead rats in every direction. Burning bodies litter the sidewalks, protesters who’ve made the ultimate sacrifice in the name of anarchy. Eric displays a shocking indifference to it all, more concerned with discussing his own self-involved questions about the minutiae of societal contradictions.

If “time is a corporate asset,” as Eric’s advisor Vija Kinsky (Samantha Morton) suggests, then Cosmopolis strips away the 24/7 urgency of capitalist intent and allows one of its titans to ponder the possibilities of his own failure. The entire film is measured in detailed prose and combustible mise-en-scene. In one of the few times Eric leaves the safe haven of his limo, he watches a pick-up basketball game from afar, asking his bodyguard Torval (Kevin Durand) if he likes to play the sport. The sudden consequences of this conversation send Cosmopolis even deeper into a psychological abyss, one in which Eric embraces his own disintegrating persona, seemingly leaving the regular world (if there ever was one) behind.

For a Cronenberg film, Cosmopolis is light on violence and body horror, but the director’s obsession with evolving ideas and tainted perspectives remains on full display. Pattinson brings a ghostly intensity to the demanding role (Eric is in every scene), a trait that becomes even more dynamic in the film’s great final sequence. But does it all add up to something more than a series of striking vignettes about the downfall of personal will? Even if Cosmopolis feels stunted by its limitations of setting and movement, it manages to make small urban spaces feel combustible, ready to explode on a moment’s notice. For that, this is quite the dangerous method.

Glenn Heath Jr. is a film critic for Slant Magazine, Not Coming to a Theater Near You, The L Magazine,andThe House Next Door. Glenn is also a full-time Lecturer of Film Studies at Platt College and National University in San Diego, CA.