I remember, as a kid, watching The Three Stooges on TV and

always feeling a little baffled to see the Stooges springing

back up from the ground at a hyper-motion, cartoonish speed; these

singular fast-motion moments usually followed a bigger gag, like one of the

Stooges being set on fire or bitten by a large animal. Still, even as a

child, it was quietly unnerving to see human beings moving faster than they . . . should.

The fast forward motion was more acceptable in cartoons like Wile E. Coyote and The Road Runner, for

example. In real life, however, people don’t move like that. But in film and

television, this fast motion effect has become more popular as years have

gone by—especially when one considers how prominent time-lapse photography has

become—so there must be an important reason for that.

In Leigh Singer’s dazzling new video, he explores the

visual rhetoric of the fast motion effect by grouping films together by shared themes and visual motifs. There are the pistol-slinging cowboys

of the Wild West in The Ballad of Cable

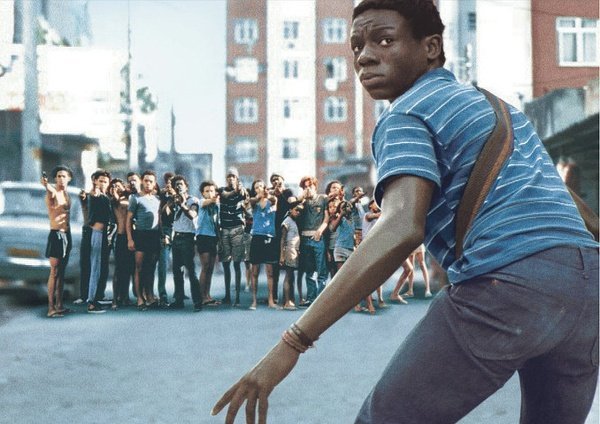

Hogue juxtaposed against the kinetic, gun-wielding rabble-rousers of Baz

Luhrmann’s updated Romeo + Juliet. Also,

there is the meta-grouping of film clips from Funny Games, Click and Caché. Each of those films visually

demonstrates the power of the fast-forward effect via an actual remote control. In Funny Games the remote control is used

to undo a fatal act, in Click it is used

as a time travel device, and in Caché it

is used as a plot-fueling investigative device to discover who has been sending

mysterious surveillance videotapes. (Note: what other video supercut

appropriately mixes an Adam Sandler comedy with a Michael Haneke film?) As

Singer’s video blazes (fast) forward to the tune of Gioachino Rossini’s

“William Tell” overture finale, it becomes clear that Singer is fascinated with

how silly we look when we’re depicted in this fast forward motion. If slow

motion dramatizes the moment, then fast motion injects a comic surge to the mise-en-scène.

Curiously enough, after a couple of viewings, I personally found the

video to be deceptively powerful in its implications of the way we process the

concept of time, especially with cinema. When speaking of the moving image in

cinema, film historian Ivor Montagu once said “No other medium can portray real

man in motion in his real surroundings.” The cinema itself is an art form that

manipulates time in more ways than one. For one thing, it freezes time: actors

are immortalized and live forever on movie screens big and small. Yet, at the

same time, it makes our perception of time decidedly pronounced. When we watch a movie, we’re subconsciously convinced that we’re seeing actions

happen in real time. But it’s not real time. The motion picture itself is

moving at a rate of 24 (or these days 30) frames per second; those are 24

captured moments—24 instances of actions or feelings that have already

happened. Still, this notion of time we won’t get back is remedied by

having at least captured some of it on film. Likewise, that fleeting concept of

speed, or the future even, is validated and realized by the fast-motion visual

effect. In our own lives, time is something we really can’t control; it passes

by with a relentless fervor. Therefore, the fast-motion effect is a

demonstration of tremendous power. If the cinema is our duplicate (or projected)

reality, then the fast motion effect represents our god-like ability to

manipulate time’s reality. It’s a unique opportunity. The kinetic speed of

the fast-motion effect is a universal touchstone; it transcends language and

culture barriers. It’s a visual representation of the voracious thirst driving life. It pushes us forward, even when we’re afraid to take that leap, because

in life, there is no rewind button.–Nelson Carvajal

Leigh studied Film and Literature at Warwick University, where he

directed and adapted the world stage premiere of Steven Soderbergh’s

‘sex, lies and videotape’. He has written or made video essays on fllm for The Guardian, The Independent, BBCi, Dazed & Confused, Total Film, RogerEbert.com

and others, has appeared on TV and radio as a film critic and is a

programmer with the London Film Festival. You can reach him on Twitter

@Leigh_Singer.

Nelson Carvajal is an independent digital filmmaker, writer and content

creator based out of Chicago, Illinois. His digital short films usually

contain appropriated content and have screened at such venues as the London Underground Film Festival. Carvajal runs a blog called FREE CINEMA NOW

which boasts the tagline: “Liberating Independent Film And Video From A

Prehistoric Value System.” You can follow Nelson on Twitter here.