As a certified crazy person, I’m here to tell you that either vampires burn in daylight or they don’t. I’ll accept no wiggle room on this. Anything less and you’ll quickly lose my suspension of disbelief. To get what I’m babbling about, this way, please. I’m talking about Homeland, which is, by the way, about almost nothing but crazy people.

Homeland, in case you’ve been busy catching up on something more realistic – I suggest Syfy’s zero-dollar wonder, Alphas – is about Carrie Mathison (Claire Danes), a C.I.A. operations officer haunted by the notion that she failed to do something that may have stopped 9/11 from happening. She was also compromised in an Iraq operation because of an American soldier who’d turned against his country.

Then a Delta Force raid uncovers Marine Sergeant Nicholas Brody (Damian Lewis) in a compound belonging to super-terrorist Abu Nazir. Brody becomes a hero but Carrie pegs him as connected to her failed op and worse, a turned sleeper agent.

When the C.I.A. turns down Carrie’s requests for invasive surveillance because dammit, we don’t do that sort of thing in America, she does it herself with some spy pals. (Alphas, with its metaphor-fraught tales of working class, genetically “super-powered” people fighting Cheney’s still-booming and lawless torture system that Homeland needs to pretend doesn’t exist, is the more clear-eyed, adult view of post-civil liberties America.) In episodes Alfred Hitchcock would love, Carrie watches Brody eat, talk and have sex with his stunningly gorgeous wife (Morena Baccarin of Firefly fame).

The season-long hook, teased sometimes to exquisitely hair-pulling extremes, is a has-he-or-hasn’t-he game of whether or not Brody has been turned and is out for big-time trouble.

And then, for me, it all went to hell.

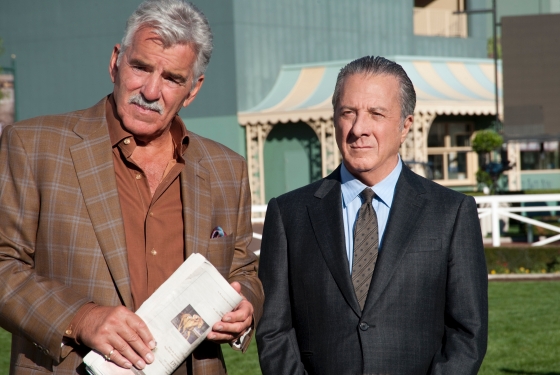

Carrie’s a character whose entire life, as the brilliant credits sequence reminds us every week, is literally defined by terrorism, fear and trying to control that fear by building a life, a personage as a person in strict control, serving her country, her profession and the one real man in her life, her mentor and father figure Saul Berenson (the mighty Mandy Patinkin).

Carrie’s a character whose entire life, as the brilliant credits sequence reminds us every week, is literally defined by terrorism, fear and trying to control that fear by building a life, a personage as a person in strict control, serving her country, her profession and the one real man in her life, her mentor and father figure Saul Berenson (the mighty Mandy Patinkin).

So of course she decides to throw it all away, including, quite possibly, the security of the United States, so she can get drunk and fuck Brody.

The show recovered in fits, some so good and others so bad it was like tuning in to get whiplash, but this was the first trumpet sounding Homeland’s true nature, and televisual literature was not included in that symphony. Homeland never dived so far as The Killing. It stayed professional, keeping us interested (and glad there were no commercial breaks where we could pause to think about its manifold absurdities). Then there was last week’s finale that led to an explosive terrorist conflagration that wasn’t – because if it was, one of the players would be taken off the board, and so much for Homeland Season Two.

But what about the vampires? What about you being crazy?

Okay. What I mean is, if a show has vampires who can never walk in sunlight because they’ll burn up in flames except when the writers need them to, well, I’m not going to be watching that show, because the writers have contempt for me, or their material, or both.

On the most basic level, that’s the deal with Carrie and Brody. In order to accept Carrie and Brody, we must accept some whoppers about what we know about bipolar disorder – if only from Oprah, what millions of people know about returning Iraq vets and P.T.S.D. and what we all know about what it is to be human.

Right, bipolar disorder. I didn’t mention that, to add some tension spice to Carrie’s character, Homeland makes Carrie suffer really badly from bipolar disorder. Like, it’s so bad that she has to take her meds every day or else she’ll go into a manic tailspin and lose her mind. The poor thing, she can’t even go to a regular doctor for those meds because the C.I.A. would kick her out as a security risk. So, she visits her psychiatrist sister on the down-low for her weekly supply, which translates into even more suspense, and some shame and anxiety to boot; this bipolar thing is paying off big-time and all they had to do was say she has it. Poor Carrie. This is going to be one rough season.

Right, bipolar disorder. I didn’t mention that, to add some tension spice to Carrie’s character, Homeland makes Carrie suffer really badly from bipolar disorder. Like, it’s so bad that she has to take her meds every day or else she’ll go into a manic tailspin and lose her mind. The poor thing, she can’t even go to a regular doctor for those meds because the C.I.A. would kick her out as a security risk. So, she visits her psychiatrist sister on the down-low for her weekly supply, which translates into even more suspense, and some shame and anxiety to boot; this bipolar thing is paying off big-time and all they had to do was say she has it. Poor Carrie. This is going to be one rough season.

Except, not so much, because on Homeland, vampires can walk in daylight, so to speak. After a few episodes, her bipolar kind of…goes away. Why? I would imagine because its rigors would get in the way of other plots leading to such flights of fancy as Carrie blowing off seeing her sister for meds so she can get blotto drunk for some hot Brody ooh la la. Unlike all of us, intemperance does nothing to aggravate her bipolar; hell, she doesn’t even get hangovers.

Yes, “us.” I outed myself a while ago on being bipolar. It’s no big thing – as long as you remotely behave like a grown-up about this controllable thing, i.e., not like Carrie.

Don't get me wrong: I don’t suggest Homeland hang itself on the horns of scientific accuracy (or a WebMD search). I just ask that it create a ‘verse where there are laws for Carrie’s condition, and then stick to those laws, like the way Vulcans can or can’t intermarry and the like. (On the other hand, absurdity met ugliness when the showrunners had Carrie, in deep depression, diagnosing herself – with her sister mutely complicit – for electroconvulsive therapy, a.k.a. shock treatment, a controversial, risky, cognition- and memory-impairing but highly photogenic treatment calling for Danes to be strapped and gagged, electrodes glued to her scalp. Then they cranked the juice as her body spasmed grotesquely. If you’re suffering from depression, there are a million other ways to get help – this is just an ignorant TV show by the guys who made the torture-happy 24.)

Don't get me wrong: I don’t suggest Homeland hang itself on the horns of scientific accuracy (or a WebMD search). I just ask that it create a ‘verse where there are laws for Carrie’s condition, and then stick to those laws, like the way Vulcans can or can’t intermarry and the like. (On the other hand, absurdity met ugliness when the showrunners had Carrie, in deep depression, diagnosing herself – with her sister mutely complicit – for electroconvulsive therapy, a.k.a. shock treatment, a controversial, risky, cognition- and memory-impairing but highly photogenic treatment calling for Danes to be strapped and gagged, electrodes glued to her scalp. Then they cranked the juice as her body spasmed grotesquely. If you’re suffering from depression, there are a million other ways to get help – this is just an ignorant TV show by the guys who made the torture-happy 24.)

Danes has created a viable person built off the showrunners’ thumbnail description and her own vision of Carrie, which manifests in endlessly fascinating halting speech patterns, “talking” body language, odd glares and more. The creators of Homeland were insanely fortunate to get such an artist.

As for Brody – good grief. Here’s a man who for eight years was brutalized, beaten, locked in solitary, became a surrogate father to an adorable child who died horribly, was forced to brutalize other Americans and, for a freshet of memorable detail, was pissed on while he bled. And yet within a day or so he’s home, and aside from limited, soon-to-improve sexual dysfunctions and some behavioral dissonances, he’s on his way to a full recovery with timeouts for plot-advancing nightmares.

Meanwhile, in Brody’s frequent shirtless scenes we see his scars and their implied memories of unimaginable months of pain and horror, which now have no apparent effect. (Even his attempted terrorist act is based not on torture, but on love of a child.) This is Spielbergism; take a sad song and make it ludicrously better, one-upping it by saying the sad song doesn’t exist even as you’re looking at it.

Meanwhile, in Brody’s frequent shirtless scenes we see his scars and their implied memories of unimaginable months of pain and horror, which now have no apparent effect. (Even his attempted terrorist act is based not on torture, but on love of a child.) This is Spielbergism; take a sad song and make it ludicrously better, one-upping it by saying the sad song doesn’t exist even as you’re looking at it.

As Brody breezed through photo ops, interrogations, his love affair, superior fathering, a remarkable act of remembrance in a church, the first steps towards a congressional run and the build-up to his terror attack, watching Homeland, for me, became the job of creating in my mind a less ridiculous backstory for Brody. Something Uwe Boll would not reject as failing to meet his stringent standards of realism. (I also had to ixnay the absurdity that any country would allow such damaged goods into the ‘burbs with no decompression process, where anyone could get to him, or the poor bastard could just blow his brains out in 24 minutes.)

Again, it’s entirely the actor’s art that pulls this nonsense off. It’s Lewis’ eye and neck muscle work, his oddly timed blinks, his general tightness of bearing suggesting things blowing up inside. Everything that nobody bothered to write.

But there were such great moments! Like when Brody and Carrie went to her family cabin in the woods, with its implications of a peaceful childhood she somehow missed, and his connection to a person who gets his deal. It was beautiful. And then she flat-out accuses him of being with Al Qaeda, and he’s back at her, yelling that he isn’t (which technically is true). It’s the spy scene we’ve always wanted to see: the breaking of both players’ pose.

Pure gold. But moments like this get lost in a spy show’s mechanics and, as Carrie’s mental illness makes that special guest appearance, devastating her just in time for dramatic effect, I’m just over these daywalking vampires. Next season, I’ll recalibrate my expectations of Homeland. I’ll enjoy the acting, the twists and turns. What do you want? It’s just TV.

Ian Grey has written, co-written or been a contributor to books on cinema, fine art, fashion, identity politics, music and tragedy. His column "Grey Matters" runs every week at Press Play. To read another piece about Drive, with analysis of common themes and images in all of Refn's films, click here.

About a third of the way through episode six of Luck, a conversation between the horse trainer Turo Escalante and the veterinarian Jo is cut short by portents. A flock of birds erupts from behind, or within, the stands; silhouetted, they look like bats. The horses freak out. Then comes an earthquake. The walls tremble. The ground shakes. And then it's over.

About a third of the way through episode six of Luck, a conversation between the horse trainer Turo Escalante and the veterinarian Jo is cut short by portents. A flock of birds erupts from behind, or within, the stands; silhouetted, they look like bats. The horses freak out. Then comes an earthquake. The walls tremble. The ground shakes. And then it's over.

Lost Girl is no big deal, and yet, for me, on sheer level of affection, it’s up there with the ludicrously better Luck, and I can barely wait for each episode to air. So WTF, right?

Lost Girl is no big deal, and yet, for me, on sheer level of affection, it’s up there with the ludicrously better Luck, and I can barely wait for each episode to air. So WTF, right? Right off, Lost Girl offers something that differentiates itself in a way that non-genre shows would be swell to emulate: a femme hero un-crushed by her backstory. While supernaturals from Buffy to Sookie to the entire cast of Once Upon a Time suffer their supernatural-ness, Lost Girl’s hero, the casually bi, trimly pumped, no-bullshit Bo (Anna Silk) accepts that she’s a deadly Fae.

Right off, Lost Girl offers something that differentiates itself in a way that non-genre shows would be swell to emulate: a femme hero un-crushed by her backstory. While supernaturals from Buffy to Sookie to the entire cast of Once Upon a Time suffer their supernatural-ness, Lost Girl’s hero, the casually bi, trimly pumped, no-bullshit Bo (Anna Silk) accepts that she’s a deadly Fae. So, want to talk about sex? Yeah? Cool. There’s tons of it here, and in the show’s world, it’s no big, which makes sense when your hero is a being whose entire deal is sexual.

So, want to talk about sex? Yeah? Cool. There’s tons of it here, and in the show’s world, it’s no big, which makes sense when your hero is a being whose entire deal is sexual. There’s the sloe-eyed Fae werewolf (Kristen Holden-Ried) who’s partial to complexly rockin’ leather combos that suggest off-label John Varvatos; the mystery bartender named Trick (Rick Howland), whose way-butch, deep-dyed denim and rolled-sleeve style is off-season Diesel all the way; and the adorable, what-the-fuck-is-she-wearing Kenzi, whose loopy gothiness suggests Betsey Johnson after listening to My Chemical Romance a lot.

There’s the sloe-eyed Fae werewolf (Kristen Holden-Ried) who’s partial to complexly rockin’ leather combos that suggest off-label John Varvatos; the mystery bartender named Trick (Rick Howland), whose way-butch, deep-dyed denim and rolled-sleeve style is off-season Diesel all the way; and the adorable, what-the-fuck-is-she-wearing Kenzi, whose loopy gothiness suggests Betsey Johnson after listening to My Chemical Romance a lot.

At some point, a show stops being a show and becomes a utility: gas, electricity, water, The Simpsons. That’s not my line; it’s cribbed from a quote about 60 Minutes by its creator, the late Don Hewitt. But it seems appropriate to recycle a point about one long-running program in an article about another when it’s as self-consciously self-cannibalizing as The Simpsons. Matt Groening’s indestructible cartoon sitcom has run 23 seasons and will air its 500th episode on February 19. It hasn’t been a major cultural force in a decade or more, unless you count 2007’s splendid The Simpsons Movie, but it’s still the lingua franca of pop-culture junkies, quoted in as many contexts as the Holy Bible and Star Wars, neither of which includes lines as funny as “Me fail English? That’s unpossible!” I haven’t seen the 500th installment yet because it wasn’t done when I wrote this piece, and that’s probably for the best; pin a thesis to any single chapter and the kaleidoscopic parade of The Simpsons will stomp it flat. Early in the show’s run we rated episodes. Now we rate seasons. In seven years, we’ll be rating decades.

At some point, a show stops being a show and becomes a utility: gas, electricity, water, The Simpsons. That’s not my line; it’s cribbed from a quote about 60 Minutes by its creator, the late Don Hewitt. But it seems appropriate to recycle a point about one long-running program in an article about another when it’s as self-consciously self-cannibalizing as The Simpsons. Matt Groening’s indestructible cartoon sitcom has run 23 seasons and will air its 500th episode on February 19. It hasn’t been a major cultural force in a decade or more, unless you count 2007’s splendid The Simpsons Movie, but it’s still the lingua franca of pop-culture junkies, quoted in as many contexts as the Holy Bible and Star Wars, neither of which includes lines as funny as “Me fail English? That’s unpossible!” I haven’t seen the 500th installment yet because it wasn’t done when I wrote this piece, and that’s probably for the best; pin a thesis to any single chapter and the kaleidoscopic parade of The Simpsons will stomp it flat. Early in the show’s run we rated episodes. Now we rate seasons. In seven years, we’ll be rating decades.

Spartacus is back with a new Spartacus. Both the new actor and the revamped series take some getting used to. For the most part, the reincarnation works, in large part because this cable franchise doesn't have a pedigree to sully. The latest edition,

Spartacus is back with a new Spartacus. Both the new actor and the revamped series take some getting used to. For the most part, the reincarnation works, in large part because this cable franchise doesn't have a pedigree to sully. The latest edition,

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The following piece about Showtime's drama Homeland contains spoilers for season one. Read at your own risk.]

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The following piece about Showtime's drama Homeland contains spoilers for season one. Read at your own risk.] This has not been my viewing experience. While Homeland is undeniably compelling, it is not a balanced show that seems very interested in presenting American intelligence services honestly. Rather, it is very validating. The all-star, critic-proof cast somehow sublimates the very undemocratic policies the show suggests need to exist in order for the Claire Danes character to succeed in her mission.

This has not been my viewing experience. While Homeland is undeniably compelling, it is not a balanced show that seems very interested in presenting American intelligence services honestly. Rather, it is very validating. The all-star, critic-proof cast somehow sublimates the very undemocratic policies the show suggests need to exist in order for the Claire Danes character to succeed in her mission. But do they really? Not according to interrogation research, which has shown time and again that torture leads to bad intelligence and creates even more terrorists. Yet Homeland embraces torture as a viable tool to get information. The captured Al Qaeda operative is tortured in a C.I.A. cell which is freezing cold (he is undressed), and plays bursts of heavy metal music and blasts strobe lights to unnerve him sufficiently to name names. Just before he is about the provide them with specific information, he manages to commit suicide. The subtext is not missed by the viewer.

But do they really? Not according to interrogation research, which has shown time and again that torture leads to bad intelligence and creates even more terrorists. Yet Homeland embraces torture as a viable tool to get information. The captured Al Qaeda operative is tortured in a C.I.A. cell which is freezing cold (he is undressed), and plays bursts of heavy metal music and blasts strobe lights to unnerve him sufficiently to name names. Just before he is about the provide them with specific information, he manages to commit suicide. The subtext is not missed by the viewer.

On a recent episode of The Graham Norton Show, the genial goofball host was plainly delighted to have Karen Gillan—known worldwide as Amy Pond, the spirited, ginger-haired companion of The Doctor on Doctor Who—on his guest couch.

On a recent episode of The Graham Norton Show, the genial goofball host was plainly delighted to have Karen Gillan—known worldwide as Amy Pond, the spirited, ginger-haired companion of The Doctor on Doctor Who—on his guest couch. The Doctor himself isn’t actually called ‘Doctor Who’. He’s the last of his race, the Timelords, obliterated after some galactic war.

The Doctor himself isn’t actually called ‘Doctor Who’. He’s the last of his race, the Timelords, obliterated after some galactic war. How you die on Doctor Who is romantic in the classical sense because it’s seen as very important. In television/film fan terms, it has additional appeal, as dying is usually a thing done in montage, a montage in waltz time.

How you die on Doctor Who is romantic in the classical sense because it’s seen as very important. In television/film fan terms, it has additional appeal, as dying is usually a thing done in montage, a montage in waltz time. If she wasn’t such a fun/hot knock-about, River Song would be unbearably tragic.

If she wasn’t such a fun/hot knock-about, River Song would be unbearably tragic. One of the ways Who works is by blindsiding you from oblique angles. Witness: “Vincent and the Doctor” is really about Amy and grief and…well, here’s what it seems to be about. The Doctor takes Amy to a museum to see Vincent Van Gogh’s paintings, then to the past to meet Vincent himself, who is miserable and being attacked my an invisible monster. With The Doctor’s help, the monster is slain, Vincent’s taken to 2010 to see that he’s a cherished artist in the hope he won’t kill himself. He still does.

One of the ways Who works is by blindsiding you from oblique angles. Witness: “Vincent and the Doctor” is really about Amy and grief and…well, here’s what it seems to be about. The Doctor takes Amy to a museum to see Vincent Van Gogh’s paintings, then to the past to meet Vincent himself, who is miserable and being attacked my an invisible monster. With The Doctor’s help, the monster is slain, Vincent’s taken to 2010 to see that he’s a cherished artist in the hope he won’t kill himself. He still does. But not necessarily. Because this is a time-travel show, it’s possible to be conversant with people earlier in their timelines.

But not necessarily. Because this is a time-travel show, it’s possible to be conversant with people earlier in their timelines.

Right, bipolar disorder. I didn’t mention that, to add some tension spice to Carrie’s character, Homeland makes Carrie suffer really badly from bipolar disorder. Like, it’s so bad that she has to take her meds every day or else she’ll go into a manic tailspin and lose her mind. The poor thing, she can’t even go to a regular doctor for those meds because the C.I.A. would kick her out as a security risk. So, she visits her psychiatrist sister on the down-low for her weekly supply, which translates into even more suspense, and some shame and anxiety to boot; this bipolar thing is paying off big-time and all they had to do was say she has it. Poor Carrie. This is going to be one rough season.

Right, bipolar disorder. I didn’t mention that, to add some tension spice to Carrie’s character, Homeland makes Carrie suffer really badly from bipolar disorder. Like, it’s so bad that she has to take her meds every day or else she’ll go into a manic tailspin and lose her mind. The poor thing, she can’t even go to a regular doctor for those meds because the C.I.A. would kick her out as a security risk. So, she visits her psychiatrist sister on the down-low for her weekly supply, which translates into even more suspense, and some shame and anxiety to boot; this bipolar thing is paying off big-time and all they had to do was say she has it. Poor Carrie. This is going to be one rough season. Don't get me wrong: I don’t suggest Homeland hang itself on the horns of scientific accuracy (or a WebMD search). I just ask that it create a ‘verse where there are laws for Carrie’s condition, and then stick to those laws, like the way Vulcans can or can’t intermarry and the like. (On the other hand, absurdity met ugliness when the showrunners had Carrie, in deep depression, diagnosing herself – with her sister mutely complicit – for electroconvulsive therapy, a.k.a. shock treatment, a controversial, risky, cognition- and memory-impairing but highly photogenic treatment calling for Danes to be strapped and gagged, electrodes glued to her scalp. Then they cranked the juice as her body spasmed grotesquely. If you’re suffering from depression, there are a million other ways to get help – this is just an ignorant TV show by the guys who made the torture-happy 24.)

Don't get me wrong: I don’t suggest Homeland hang itself on the horns of scientific accuracy (or a WebMD search). I just ask that it create a ‘verse where there are laws for Carrie’s condition, and then stick to those laws, like the way Vulcans can or can’t intermarry and the like. (On the other hand, absurdity met ugliness when the showrunners had Carrie, in deep depression, diagnosing herself – with her sister mutely complicit – for electroconvulsive therapy, a.k.a. shock treatment, a controversial, risky, cognition- and memory-impairing but highly photogenic treatment calling for Danes to be strapped and gagged, electrodes glued to her scalp. Then they cranked the juice as her body spasmed grotesquely. If you’re suffering from depression, there are a million other ways to get help – this is just an ignorant TV show by the guys who made the torture-happy 24.)