Since its premiere at the Venice Film Festival, Gravity has generated a tremendous

amount of reverential hype, but with its general release the inevitable

critical backlash is beginning to roll—or rather troll—its way across the

web. Where once critics compared Cuarón’s

film favorably with the work it most resembles, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, it is now being

criticized for falling short of that earlier film’s ambition. While Gravity’s

special effects are sufficiently stunning to distract, potentially, from

the film’s intellectual and emotional impact, it is a much smarter film than it

is generally given credit for being. Far

from being mere imitation or homage, Gravity

offers an ingenious and moving revision and critique of its predecessor, one

that begins in the stars but returns us to our own earthly soil. Cuarón’s

achievement is to make our own planet and the fragile lives it sustains seem as

miraculous as the cosmos that surrounds it.

Both films concern space travel, yet while 2001 reflects the sense of wonder inspired

by the golden era of space travel, Gravity

shows a space program in which the optimism of its early years has been gutted,

along with its budget. Much of the film

takes place in abandoned space stations, interiors clogged with the trash

and cast-off tchotchkes of departed astronauts. The opening scene shows a technical crew repairing

the Hubble telescope above a jaw-dropping view of the Earth, but they seem

almost bored, or, like Dr. Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock), nauseous, as she

attempts to fight off the effects of zero-g by concentrating on her work, evidently

as dull to her as the scenery might be grand to a novice.

But dullness and nausea quickly give way to terror as the

hurtling debris from an exploded Russian satellite strikes the repair crew, and

it is telling that the film’s greatest threat comes from, essentially,

garbage. Stone is sent spinning out of

control into space, in a scene clearly derived from that harrowing moment in 2001 when Frank Poole hurtles into the

darkness when his oxygen hose is severed. Yet it is at this early point that Cuarón begins to reverse the direction

of Kubrick’s odyssey: whereas the one surviving astronaut of 2001’s Jupiter crew will set out on a

journey “Beyond the Infinite,” Cuarón will take us into the finite, as Ryan

Stone confronts her own mortality.

Throughout Gravity we

are reminded of how fragile human beings are, how vulnerable our bodies, as we

witness Stone being thrown and pummeled through a series of deadly and dazzling

physics lessons. As in Children of Men, Cuarón’s elaborately

choreographed camera work is used to place us in almost unbearably intimate

proximity to the fear and suffering of his characters. We hear and see Stone’s breathing until it

becomes almost an extension of our own. The awkward bulkiness of her suit only serves to

emphasize the frailty of a body it cannot hope to protect.

While some of these elements are also present in Kubrick’s 2001, human frailty and the technologies which sustain it are emphasized only to underscore the film’s final

movement towards transcendence. Though

there are a wide range of possible interpretations of 2001’s final image of a gigantic fetus floating in space, it

is clearly meant to represent some kind of rebirth, one in which David Bowman,

and by extension the human race, has moved on to its next, possibly final,

evolutionary stage, a journey that began long ago, when a giant black monolith

taught early hominids how to use tools. Ryan

Stone, on the other hand, will journey in the opposite direction, towards a

humanness that is less cosmic, more earthly.

Cuarón explicitly references Kubrick’s final image when

Stone finally makes it to the shelter of the International Space Station. There, she frees herself from her burdensome

suit and floats, fetus-like, in the oxygenated atmosphere. The image is mesmerizing, and Kubrick-like in

its use of one-point perspective; yet Cuarón’s fetus image is radically

different in its thematic implications. Whereas Dave Bowman’s transformation signals another, clearly

post-human, phase of evolution, Cuarón emphasizes Stone’s humanity, her

corporeal, embodied self. Cuarón

replaces Kubrick’s image of transcendence with one of vulnerability.

Given the fact that most of Gravity is spent free of the earth’s pull, the title might seem

ironic, at least until we learn more about Stone’s personal history. The absorption in work that marked her first

appearance in the film is in large part an escape from the painful memory of the

death of her young daughter, who fell while playing on the schoolyard. The randomness of this tragic event serves to

underscore the film’s preoccupation with human frailty, as both mother and

daughter find themselves pulled by natural forces beyond their control. Rather than transcend these merely physical

forces, however, Cuarón asks us to accept, and even embrace, them.

In what is, to me, the film’s most powerful scene, Stone,

alone in an abandoned space station and desperate for the sound of another

voice, searches the airwaves for some signal from Earth. At last, out of the static, there emerges a

foreign male voice, apparently drunk, and laughing. Stone seems a little disappointed, until she

hears a dog in the background. Attempting to transcend the language barrier, she makes dog sounds, at

first in the hopes of engaging her human counterpart, but eventually engaging the

nonhuman. We are pulled into an intimate

close-up as Stone begins to howl, mournfully, along with the dog, shedding

tears that float into the oxygenated air, forming globules like tiny

planets. She has found a place in herself prior to speech, allowing her to give vent to sorrows deeper than human

language. Like the dog, she is an

embodied, vulnerable creature, and in evolutionary terms they share a common

ancestry, and a common planet.

The film’s final scene will make this evolutionary narrative

even more explicit, but I don’t want to give anything away, since this is a thriller

after all, isn’t it? While the film’s

action sequences have been justly praised as some of the most gripping and

technically accomplished ever filmed, I would argue that they are there

primarily to serve the central human narrative. This narrative is told through minimal dialogue and maximal images, yet

it is as clear and direct as fairy tale or myth. If we compare Cuarón’s space

sequences with Kubrick’s, a clear difference emerges: though the space-ships of

2001 might dance to the rhythms of a

Strauss waltz, they are cold and inhuman, whereas in Gravity the human form is at the center of nearly every shot. One might compare the presence of CGI technology

in Gravity to that of the HAL

computer in 2001: each might guide

our journey, but after a certain point we need to cut them loose to discover

how our story will turn out.

Jed Mayer is an Associate Professor of English at the State University of New York, New Paltz.

For me, Room 237 is more interesting as a commercial case study, along the same lines as Christian Marclay’s phenomenally successful art installation The Clock, a found footage work incorporating thousands of film clips into a functional, 24 hour video timepiece. The Clock has created a sensation nearly everywhere it has exhibited, including its current installation at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, where the museum’s twitter feed posts hourly wait times for viewing. Such commercially successful applications of found footage in both The Clock and Room 237 mark a distinct shift in fortunes from how found footage art has been received in the past.

For me, Room 237 is more interesting as a commercial case study, along the same lines as Christian Marclay’s phenomenally successful art installation The Clock, a found footage work incorporating thousands of film clips into a functional, 24 hour video timepiece. The Clock has created a sensation nearly everywhere it has exhibited, including its current installation at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, where the museum’s twitter feed posts hourly wait times for viewing. Such commercially successful applications of found footage in both The Clock and Room 237 mark a distinct shift in fortunes from how found footage art has been received in the past.

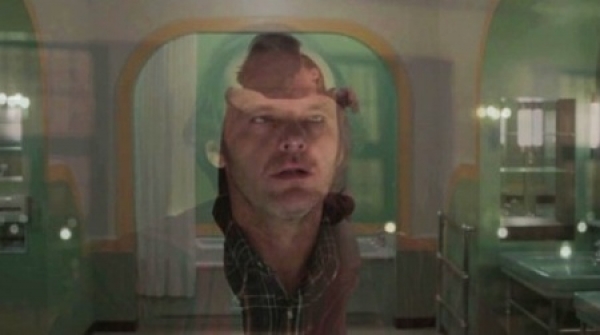

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining is not generally considered a family picture, but it is certainly one of the most brutally honest films ever made about the nature of family relationships. I discovered this when seeing the film for the first time with my father when I was fourteen. My father took me to dozens of R-Rated films when I was growing up, which reflected, I think, his trust in my maturity rather than any negligence about what was morally appropriate for children (though there was some of that too). Many of my fondest memories of my father involve going to the movies, and going to R-Rated films was something we usually did together, without my Mom or my sister. For two guys who hated sports, this was our equivalent of playing catch. We’d seen plenty of horror films together, but I never anticipated that a horror film would hit quite so close to home as The Shining.

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining is not generally considered a family picture, but it is certainly one of the most brutally honest films ever made about the nature of family relationships. I discovered this when seeing the film for the first time with my father when I was fourteen. My father took me to dozens of R-Rated films when I was growing up, which reflected, I think, his trust in my maturity rather than any negligence about what was morally appropriate for children (though there was some of that too). Many of my fondest memories of my father involve going to the movies, and going to R-Rated films was something we usually did together, without my Mom or my sister. For two guys who hated sports, this was our equivalent of playing catch. We’d seen plenty of horror films together, but I never anticipated that a horror film would hit quite so close to home as The Shining. We learn during Jack’s interview that the Torrances have just moved to Colorado from Vermont, but it is not until a pediatrician is called in to check on Danny after he experiences a blackout that we learn more of the details of their past life. During this interview the camera focuses on Wendy, as she awkwardly describes to the doctor how Jack once dislocated his son’s shoulder in a fit of drunken rage. The violence of the event is masked by Shelley Duvall’s nervous smile and chirpy voice, her forced cheeriness deflecting the viewer’s empathy. The alleged “happy ending” to the story, that Jack quit drinking as a result of this incident and hasn’t had a drink for five months, is further undercut when we shift from Wendy’s face to that of the doctor, who looks frankly horrified. The camera resumes its deep focus, isolating Wendy from the doctor by framing them on either side of a series of bookshelves with the books arranged in a nervous zigzag. While today we might expect a call to Child Protective Services, in the world of The Shining such confessions only serve to further isolate the family.

We learn during Jack’s interview that the Torrances have just moved to Colorado from Vermont, but it is not until a pediatrician is called in to check on Danny after he experiences a blackout that we learn more of the details of their past life. During this interview the camera focuses on Wendy, as she awkwardly describes to the doctor how Jack once dislocated his son’s shoulder in a fit of drunken rage. The violence of the event is masked by Shelley Duvall’s nervous smile and chirpy voice, her forced cheeriness deflecting the viewer’s empathy. The alleged “happy ending” to the story, that Jack quit drinking as a result of this incident and hasn’t had a drink for five months, is further undercut when we shift from Wendy’s face to that of the doctor, who looks frankly horrified. The camera resumes its deep focus, isolating Wendy from the doctor by framing them on either side of a series of bookshelves with the books arranged in a nervous zigzag. While today we might expect a call to Child Protective Services, in the world of The Shining such confessions only serve to further isolate the family.

Several years ago, I was delighted to discover how well The Shining works as a Christmas ghost story, when my wife and I were spending the holiday with her family. After Christmas dinner we got into a conversation about times when we’d been snowbound, and this led us gradually to a discussion of Kubrick’s film. We reminisced on favorite scenes while sipping hot toddies, until we all agreed that watching this would be much more entertaining than our traditional viewing of A Christmas Carol. Just as the cold outside makes the warmth inside more welcoming, so the vision of a family tearing itself apart onscreen makes one feel closer to the family on the couch. Jack Nicholson’s malignly comic performance provides just the right sense of dangerous hilarity, heightening the sense of camaraderie, and the whole family can cheer at the end as Danny ingeniously escapes his father’s pursuit and reunites with his mother. It’s easy to forget, but The Shining actually does have a happy ending.

Several years ago, I was delighted to discover how well The Shining works as a Christmas ghost story, when my wife and I were spending the holiday with her family. After Christmas dinner we got into a conversation about times when we’d been snowbound, and this led us gradually to a discussion of Kubrick’s film. We reminisced on favorite scenes while sipping hot toddies, until we all agreed that watching this would be much more entertaining than our traditional viewing of A Christmas Carol. Just as the cold outside makes the warmth inside more welcoming, so the vision of a family tearing itself apart onscreen makes one feel closer to the family on the couch. Jack Nicholson’s malignly comic performance provides just the right sense of dangerous hilarity, heightening the sense of camaraderie, and the whole family can cheer at the end as Danny ingeniously escapes his father’s pursuit and reunites with his mother. It’s easy to forget, but The Shining actually does have a happy ending. The film has become a family tradition for us, but underneath the sense of kinship and connection with my in-laws that the film seems to foster, are more disturbing family memories. Like Jack Torrance, my father was an alcoholic, and several scenes in the film capture the experience of being the child of an alcoholic better than any film I know. In particular, I find especially troubling the scene where Danny quietly enters the chamber of his sleeping father to retrieve his toy fire engine and finds his father sitting awake on his bed. In a kind of narcoleptic daze Jack calls Danny over for a little talk. As disturbing as is Jack’s affectless attempt at speaking on a child’s level, what most troubled me about this scene when I first saw it with my father was the benumbed wariness of Danny’s responses to his father’s affection. What is most unsettling about being the child of an alcoholic is the sense of uncertainty: I never knew which version of my father I was dealing with from night to night, and this is what I saw in Danny’s response.

The film has become a family tradition for us, but underneath the sense of kinship and connection with my in-laws that the film seems to foster, are more disturbing family memories. Like Jack Torrance, my father was an alcoholic, and several scenes in the film capture the experience of being the child of an alcoholic better than any film I know. In particular, I find especially troubling the scene where Danny quietly enters the chamber of his sleeping father to retrieve his toy fire engine and finds his father sitting awake on his bed. In a kind of narcoleptic daze Jack calls Danny over for a little talk. As disturbing as is Jack’s affectless attempt at speaking on a child’s level, what most troubled me about this scene when I first saw it with my father was the benumbed wariness of Danny’s responses to his father’s affection. What is most unsettling about being the child of an alcoholic is the sense of uncertainty: I never knew which version of my father I was dealing with from night to night, and this is what I saw in Danny’s response.

I have always been drawn to visions of the future, but little did I know what brutal images were held on the Beta videocassette of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange I rented at the tender age of ten. Although the film had been banned in Great Britain, it was shelved innocently in the science fiction section of Johnny’s TV, and no one would have thought of suggesting that this might be inappropriate viewing for a child. By the time I reached the infamous scene where Alex and his droogs violently assault and rape a woman while forcing her husband to watch, I knew that I had crossed some indefinable line and that I couldn’t turn back. Later, wondering what had led me to this most disturbing of film experiences, I realized that it had all started with a filmstrip.

I have always been drawn to visions of the future, but little did I know what brutal images were held on the Beta videocassette of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange I rented at the tender age of ten. Although the film had been banned in Great Britain, it was shelved innocently in the science fiction section of Johnny’s TV, and no one would have thought of suggesting that this might be inappropriate viewing for a child. By the time I reached the infamous scene where Alex and his droogs violently assault and rape a woman while forcing her husband to watch, I knew that I had crossed some indefinable line and that I couldn’t turn back. Later, wondering what had led me to this most disturbing of film experiences, I realized that it had all started with a filmstrip.  Such primitive media technologies have a distinctive charm that, like Czech animation or natural history dioramas, is indistinguishable from their premature obsolescence. There is something poignant about the notion of watching sequences of still images in an age of television and film. I remember settling into the experience of viewing these slow-moving narratives as into a kind of meditational trance, broken occasionally by the pitch bend and warbling of stretched cassette tape. How fitting, then, that this peculiar medium would be the means of introducing me to the strange world of early electronic music.

Such primitive media technologies have a distinctive charm that, like Czech animation or natural history dioramas, is indistinguishable from their premature obsolescence. There is something poignant about the notion of watching sequences of still images in an age of television and film. I remember settling into the experience of viewing these slow-moving narratives as into a kind of meditational trance, broken occasionally by the pitch bend and warbling of stretched cassette tape. How fitting, then, that this peculiar medium would be the means of introducing me to the strange world of early electronic music. Seeing the horrific rape scene in the film left a similarly indelible impression on me, and proved to be as effective an education in the immorality of violence against women as the education the film’s protagonist experiences as part of his aversion therapy. This scene remains the image that comes to mind whenever I hear the word rape, and it gave me an early, brutal understanding of the uniquely sadistic and degrading nature of this act. If prostitution can be glibly referred to as the oldest profession, then surely rape is the oldest crime. Ironic, then, that the film I had hoped would take me into an imagined future ended up exposing me to the primitive and the barbaric.

Seeing the horrific rape scene in the film left a similarly indelible impression on me, and proved to be as effective an education in the immorality of violence against women as the education the film’s protagonist experiences as part of his aversion therapy. This scene remains the image that comes to mind whenever I hear the word rape, and it gave me an early, brutal understanding of the uniquely sadistic and degrading nature of this act. If prostitution can be glibly referred to as the oldest profession, then surely rape is the oldest crime. Ironic, then, that the film I had hoped would take me into an imagined future ended up exposing me to the primitive and the barbaric.  As a teenager I would return to the film, drawn to the stark images of a retrogressive future that seemed closer than ever. I later learned that most of the film was shot, not on sets, but in actual London settings, including Thamesmead, one of many planned urban communities of the 1960s and 1970s that produced scenarios not unlike that presented in Kubrick’s film, when families experienced traumatic feelings of disorientation as they relocated to blocks of buildings that had little in common with the neighborhoods they’d grown up in. What was an unpleasant reality for many Londoners became for me a kind of stark fantasy image, one on which I gazed obsessively in its various permutations, as seen on album covers and music videos produced by a new wave of electronic artists, like Gary Numan, John Foxx, and The Human League, composing pop music for a dark future.

As a teenager I would return to the film, drawn to the stark images of a retrogressive future that seemed closer than ever. I later learned that most of the film was shot, not on sets, but in actual London settings, including Thamesmead, one of many planned urban communities of the 1960s and 1970s that produced scenarios not unlike that presented in Kubrick’s film, when families experienced traumatic feelings of disorientation as they relocated to blocks of buildings that had little in common with the neighborhoods they’d grown up in. What was an unpleasant reality for many Londoners became for me a kind of stark fantasy image, one on which I gazed obsessively in its various permutations, as seen on album covers and music videos produced by a new wave of electronic artists, like Gary Numan, John Foxx, and The Human League, composing pop music for a dark future. Though I still deplored the violent acts of Alex and his mates, A Clockwork Orange resumed its earlier place among my obsessions. As with Alex, the film’s earlier aversion therapy didn’t take. Perhaps that’s because none of us experience only one form of social conditioning. While Alex is given nausea-inducing drugs meant to establish negative associations with the violent images on screen, his therapists clearly underestimate the staying power of his previous conditioning.

Though I still deplored the violent acts of Alex and his mates, A Clockwork Orange resumed its earlier place among my obsessions. As with Alex, the film’s earlier aversion therapy didn’t take. Perhaps that’s because none of us experience only one form of social conditioning. While Alex is given nausea-inducing drugs meant to establish negative associations with the violent images on screen, his therapists clearly underestimate the staying power of his previous conditioning.