Read our critics' personal predictions of who SHOULD win the awards, and who WILL win the awards, at Cannes 2012:

Glenn's Predictions:

With the last Cannes competition screening in the books, let the award prognostications begin. Since Cannes 2012 has been the year of non-consensus, trying to pick the award winners is like playing a game of musical chairs. But here goes:

Best Actor:

If there’s any justice in this world, Denis Lavant will carry the day for his breathtaking, transformative performance in Holy Motors. There’s no male performance in competition that compares. Aniello Arena of Reality has an outside chance of pulling an upset here, as does Jean-Louis Trintignant of Amour, but I see the latter and his co-star Emmanuelle Riva getting a special mention award instead.

Will and Should Win: Denis Lavant, Holy Motors

Best Actress:

This category is more of a crapshoot, with Margarete Tiesel (Paradise: Love), Marion Cotillard (Rust and Bone) and Emmanuelle Riva (Amour) all serious competitors. Cotillard should take it as the local favorite, especially since Paradise: Love is an incredibly divisive film and the performances in Amour should get their own award.

Should Win: Margarete Tiesel, Paradise: Love

Will Win: Marion Cotillard, Rust and Bone

Jury Prize:

Sergei Loznita’s In the Fog has an outside chance at the Palme, but I see him getting either the Jury Prize (his great War film would be my choice) or Best Director for his brilliantly dire work. But my prediction for third place is Cristian Mungui’s stark indictment of religious ideology, Beyond the Hills, a resounding technical achievement hindered by taxing hysterics and a blunt “fish-in-a-barrel” ending.

Should Win: In the Fog

Will Win: Beyond the Hills

Best Screenplay:

Andrew Dominik’s talky gangster film Killing Them Softly deserves this one for its amazingly dense dialogue sequences and interesting subplots. But I see David Cronenberg’s talky satire Cosmopolis pulling this one out. If Resnais doesn’t get the Palme, he might get a Screenplay win in return.

Should Win: Killing Them Softly

Will Win: Cosmopolis

Best Director:

It would be wonderful if Wes Anderson were honored with Best Director for Moonrise Kingdom, the one American film in Competition that grows more complex and enjoyable by the day. But he seems like a long shot despite the overall warm reception. If Holy Motors doesn’t win any other award, Carax has a shot at director as well. But the aforementioned Loznitsa will walk away with the prize.

Should Win: Wes Anderson, Moonrise Kingdom

Will Win: Sergei Loznitsa, In the Fog

Grand Prix:

Michael Haneke’s stunning Amour has been the one film most festivalgoers agree on, gaining both critical acclaim and audience praise. But since the Danish director won for his last film (The White Ribbon), look for it to receive the runner-up prize.

Will and Should Win: Amour

Palme d’Or:

Four films have a viable shot at winning the Palme d’Or (Amour, You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet, Like Someone in Love, and Holy Motors), but directors of two (Haneke and Kiarostami) have already won the top prize. Kiarostami’s brilliant Like Someone in Love deserves the award for its audacity, complexity, and sheer thematic force, but it’s hard to imagine the jury giving this divisive a film the big prize. I’m going with Resnais, mostly because he’s never won the award and this is reportedly his last film. The master of the French New Wave will undoubtedly be jury president Nanni Moretti’s sentimental choice. But don’t count out Leos Carax’s loony Holy Motors, the one film in competition with the most impassioned momentum.

Should Win: Like Someone in Love

Will Win: You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet

SIMON'S PREDICTIONS:

I’m usually pretty bad at prognosticating anything, so please do take that in mind when reading these predictions. I’ve tried to keep in mind the warm reception some of these films have gotten from colleagues, audience members and myself as well as what a jury (any jury, really) might be inclined to reward. But really, this is a tough year to predict. There have been a number of exceptional films in competition and also a bunch of awful ones, too. Choose wisely, Nanni and co.

Best Actor:

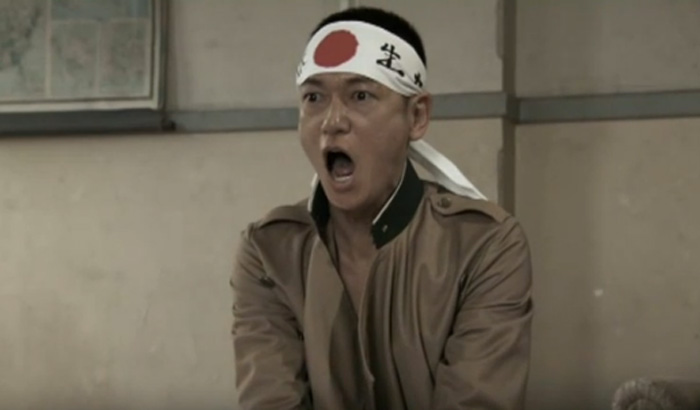

Who Will Win: Denis Lavant, Holy Motors. Lavant plays an actor that transforms from one scene to the next in Leos Carax’s astounding ode to film (the rise of digital cinema weights heavily on him). I tend to think this will win because Lavant’s not only typically versatile but he also has a very physical and demanding role. It’s an impossible-to-miss performance.

Who Should Win: Denis Lavant, Holy Motors. He really is that good, you guys.

Best Actress:

Who Will Win: Emanuelle Riva, Amour. Admittedly, there’s a look-at-me quality to the role that Riva plays in Michael Haneke’s suffocating and disturbing (but in a rewarding way!). How could an award’s body ignore the actress that plays an elderly woman losing her memory? At the same time, Riva really is excellent so this seems like an easy pick.

Who Should Win: Anne Consigny, You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet! Alain Resnais’s newest (and possibly last) film is characteristically rich. He gathers a bunch of actors and has them perform the same roles as each other for the sake of a meta-textual and meta-physical commentary on, well, life, death and performance. Of the three actresses that play Eurydice in the film, Consigny stands out the most, however. This is saying something, considering that she’s playing the same part as the equally impressive Sabine Azema.

Jury Prize:

Who Will Win: Like Someone in Love. I’m not even sure what this award is for. What’s this award for? In any case, Nanni Moretti, the competition jury’s president, apparently made a push for Like Somone in Love director Abbas Kiarostami’s The Taste of Cherry to win a prize. And Kiarostami’s “due,” as they say. Oh, and the movie’s good, too.

Who Should Win: Holy Motors. I seriously don’t know what this prize is. And Carax’s new film is kind of amazing but I don’t think it will win the Palme. Still, I think it will win…something, certainly. This prize could just as easily go to Moonrise Kingdom though.

Best Screenplay:

Who Will Win: After the Battle. Again, being the jaded ass that I am, I don’t think jury members can resist this film’s blunt, dialectical discussion of the recent and highly publicized Egyptian coup. I mean, they should try to resist it, but I think it’ll be a difficult resistance.

Who Should Win: Cosmopolis. David Cronenberg’s adaptation of Don Delillo’s novel is seriously impressive. The changes he’s made to Delillo’s narrative are small but significant, as they only serve to bolster Delillo’s complex and fascinating story. Cronenberg’s script is the backbone for a very well-paced and canny bit of speculative fiction (ie: scifi). So it won’t win but it should.

Best Director:

Will Win: Reality. I rather like Matteo Garrone and am okay with the assured but subtle creative decisions he made for this film. But honestly, the real reason I chose this one is because Garrone's apparently stuck around. So, hey: the prize goes to the guy that directed First Love. Noiiiiice.

Should Win: Killing Them Softly. You can say what you want about the film's obnoxious politics but Dominik is one assured filmmaker. The way he juggles the acidic irony of certain lines of dialogue with relatively playful song cues and then, you know, a serious heist plot–really impressive, even if the rest of the film isn't as good as his previous efforts.

Grand Prix:

Who Will Win: Holy Motors. Leos Carax’s deeply felt passion project has understandably impressed almost everyone I’ve talked to at Cannes. It’s a great film and a complex one, so I tend to think it has something for everyone. Plus, it’s about cinema. So the guys that thought The Artist would tickle the 2011 Cannes jury’s fannies, I mean fancies might have just been off by a year.

Who Should Win: Cosmopolis. I dunno, guys, it takes a lot of skill to pull off an adaptation of Delillo’s knotty source novel that’s as great as Cronenberg’s is. And this sure as hell won’t win the Palme. Plus, the subject’s contemporary, it’s hip, it’s happening. I dunno, I think this movie should win a major award and as long as I’m being both hopeful and realistic, this is probably the prize it should win.

Palme D’Or:

Who Will Win: You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet! Alain Resnais is considered to be the favorite for the Palme by everyone and their mother because, well, he’s old, probably dying and a great fucking filmmaker. So he’s “overdue,” as they say. Oh, and his new movie is really good, too.

Who Should Win: The Paperboy. Make no mistake: Lee Daniels’ new movie is not good by any stretch of the imagination. He confuses sleazy mugging with meeting tawdry material at its own level and trite notions of sex and race as if they were deep sentiments to live by. But holy guacamole, if this movie won, Cannes would be burned to the ground overnight. The prize would be stolen, along with viewers' hearts (?!), by the guy that directed such faux-works of holier-than-thou kitsch as Shadowboxer and Precious: Based on the Novel ‘Push’ by Sapphire. How awesome would that be, right?!

Glenn Heath Jr. is a film critic for Slant Magazine, Not Coming to a Theater Near You, The L Magazine,andThe House Next Door. Glenn is also a full-time Lecturer of Film Studies at Platt College and National University in San Diego, CA.

Simon Abrams is a New York-based freelance arts critic. His film reviews and features have been featured in The Village Voice, Time Out New York, Slant Magazine, The L Magazine, The New York Press and Time Out Chicago.He currently writes TV criticism for The Onion AV Cluband is a contributing writer at the Comics Journal.His writings on film are collected at the blog, Extended Cut.

Glenn Heath Jr.

Glenn Heath Jr. Simon Abrams

Simon Abrams