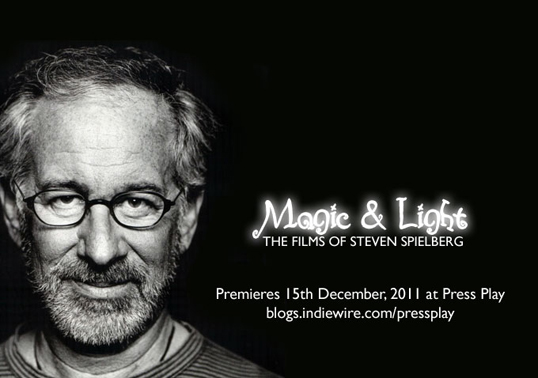

[Editor's Note: Press Play is proud to present Chapter 2 of our first video essay series in direct partnership with IndieWire: Magic and Light: The Films of Steven Spielberg. This series examines facets of Spielberg's movie career, including his stylistic evolution as a director, his depiction of violence, his interest in communication and language, his portrayal of authority and evil, and the importance of father figures — both present and absent — throughout his work.

Magic and Light is produced by Press Play founder and Salon TV critic Matt Zoller Seitz and coproduced and narrated by Ali Arikan, chief film critic of Dipknot TV, Press Play contributor, and one of Roger Ebert's Far Flung Correspondents. The Spielberg series brings many of Press Play's writers and editors together on a single long-form project. Individual episodes were written by Seitz, Arikan, Simon Abrams and Aaron Aradillas, and cut by Steven Santos, Serena Bramble, Matt Zoller Seitz, Richard Seitz and Kevin B. Lee. To watch Chapter 1: Introduction, go here. To watch Chapter 3: Communication, click here. To watch Chapter 4: Evil & Authority, click here. To watch Chapter 5: Father Figures, click here. To watch Chapter 6: Indiana Jones and the Story of Life, click here.]

When you think of the films of Steven Spielberg, violence may not be the first thing that comes to mind. But Spielberg’s films wouldn’t be Spielberg’s films if he didn’t show and imply violent actions. Violence is just another color on Spielberg’s palette and he’s not shy about using it, either to excess or with moderation. And the presentation of the violence reveals a lot about Spielberg’s sense of what the audience can handle, and how far he can go as a director.

In fact, you can tell what kind of Spielberg film you’re watching based solely on the way he shows violence.

As a child, Spielberg used to worship the violent Grand Guignol violence of EC Comics – specifically such lurid titles as Shock Suspense Stories and Weird Science. But he also gorged himself on 1950s network television and old Hollywood movies, which for the most part had a much more circumspect attitude toward violence.

Look over his filmography, and you’ll see the tension between those two tendencies – excess and moderation. But you’ll also notice that he lets one tendency take over when it shouldn’t. Spielberg modulates the tenor of the violence he employs to suit the content of his films.

There’s no explicit gore in the director’s early made-for-TV films Something Evil and Duel. Instead, it’s mostly about implication.

Three years after Duel came Jaws, which defined the term “blockbuster hit.” The film famously opens with a swim at dawn, and the shredding of a helpless bather. The scene strikes the perfect balance between evident agony and visible damage to the body. We don’t see the shark’s teeth digging into the girl, but we do sense the shark’s power. The level of brutality is shocking yet perfectly judged, and for this type of film, it’s necessary. For the mass hysteria and panic in Jaws to be immediately shared by characters and viewers alike, there has to be blood in the water. And boy, is there.

Note that the film amps up the violence incrementally as the story goes on, each death a bit more front-and-center than the last, in much the same way that Spielberg keeps the shark mostly off camera at first, gradually unveiling it in bits and pieces.

Contrast this with the sheer excess of some of the violence in the Indiana Jones films, which Spielberg made with his old friend, producer George Lucas.

The original Indy movie, Raiders of the Lost Ark, is filled with acts of violence both implicit and explicit. Its finale is as over-the-top violent as the psychokinetic insanity of such films as The Fury and Scanners.

The heritage of pulp becomes even more apparent in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, which is almost certainly the pulpiest of the four Indy movies.

In scenes such as the opening – in which Indy uses a shish kebab skewer in a unique and uncomfortable way – Spielberg shows us he’s ready and willing to serve up cartoonish and wildly exaggerated mayhem.

The Temple of Doom is adorned with skulls and skeletons in various stages of decomposition, reminding the viewer of the dated but effectively excessive tone that Spielberg is adopting here.

The banquet scene in Pankot Palace is particularly grisly and over-the-top. At one point Kate Capshaw’s squeamish American is served a bowl of soup that suggests the palace’s kitchen is being run by the Crypt Keeper from EC Comics’ Tales from the Crypt.

And yet the Hitchcockian subtlety of Jaws and the gleefully boyish excess of the Indy films are but two of Spielberg’s violent modes. He finds other ones in his historical dramas – especially the ones that deal with war.

Empire of the Sun – an adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s uses violence in a very different way than Saving Private Ryan because, where Saving Private Ryan is about the chaos of being in war – the actual EXPERIENCE of combat – Empire of the Sun is about the disappearance of life as the film’s young protagonist once knew it. It’s a subtle distinction, and this is – for all its scope – a subtle movie, as evidenced by the power that Spielberg wrings from a single, relatively minor act of violence that doesn’t even draw blood.

In Empire of the Sun, James Graham, the film’s young British protagonist, soon realizes that the sanctity and the familiarity of his home have disappeared. His maid, whom he used to boss around, slaps him when he catches her stealing furniture. He can’t process what this action means. He just stands there stunned and lets the maid walk away, averting her eyes so that they don’t meet with his as she steals his furniture.

A similarly direct and gritty approach can be seen in the combat and atrocity scenes of Spielberg’s violent historical dramas.The D-Day sequence in Saving Private Ryan is the apex of the de-humanizing nightmare that its characters endure. The entire point is to put you in the middle of it and show you everything, even things no person should see. Spielberg goes so far as to make the bullets whizzing through the air and water visible. That more than can be said for the individual faces of the American soldiers, who for the most part are depicted as cannon fodder – bodies hurled up on a German-held beach to die by the thousands. The selective shakiness of Spielberg’s camera adds another layer of surrealism to the experience of watching this volatile scene.

This is a far cry from the gun battles in the Indiana Jones pictures, which take place in roughly the same era and have similar firearms, some of them wielded by Nazi Germans.

Even if you were to compare two of Spielberg’s strictly fantasy-based films, Jurassic Park and A.I.: Artificial Intelligence, you’d find that you’re seriously different territory just by looking at the way he depicts violence.

By the time Spielberg made Jurassic Park, the MPAA had created the PG-13 rating thanks to films like Joe Dante's Gremlins, which Spielberg executive produced, and Spielberg's own Temple of Doom. These films and others shepherded by Spielberg wrap fundamentally lurid material in family-friendly package. But the science fiction films – like the Indy films, for the most part – are very careful not to go too far, too soon. They’re a bit like Jaws in that respect – a comparison made official by the opening kill in Jurassic Park, which is staged in a manner very similar to the bather’s death that opens Jaws.

Spielberg is so adept at balancing gore against human distress that in his films, as in Hitchcock’s, you often think you’re seeing more than you actually are. For example, it’s hard not to misremember that, during the scene in which Wayne Knight's opportunistic programmer gets spat on by a dinosaur, nothing that grisly is explicitly shown. He's screaming loudly though, and there's gunk on his face and his shirt, and John Williams's score is blaring. But in terms of what’s actually shown it’s a pretty restrained scene. The whole movie is more restrained than we may remember. In fact, the most horrendous violence in the film is not shown at all. The scene in which an unseen pack of raptors massacres a living cow happens off-screen, and is more unnerving because of it.

When Sam Neill describes to a snot-nosed kid how raptors used to gut their prey and ate them alive, the full brunt of the horror is conveyed verbally, without any images to assist it.

Artificial Intelligence is also set in a pulpy, theme-park-ride-friendly fantasy setting, but the film is decidedly darker than the Jurassic Park films, or almost any Spielberg films for that matter. And as a result, the violence here is pointedly less rambunctious. During the Flesh Fair scene, David the boy robot watches as outmoded robots get torn apart, shot through hoops of fire and dismantled in various different grisly ways. The Flesh Fair is supposed to be a carnival: a three-ring circus and so-called "celebration of life" that requires the death of inorganic robots to thrive.

On some level we may be aware that if the violence inflicted on these robots were inflicted on actual humans, we would probably turn away from it onscreen. That subliminal awareness plays into the movie’s central preoccupation: at what point should a biologically non-human person be considered, for all intents and purposes, human? If it feels synthesized feelings, are they not still feelings? Shouldn’t simulated pain still be considered pain?

The most upsetting scene in Artificial Intelligence might be the one in which David is abandoned by the side of the road by his distraught foster mother. The moment when he realizes what she's doing is heart-breaking. David's squeals of panic are so tortured that you're afraid that something bad is about to happen – something that will hurt both him and his mother. The juxtaposition of this scene with the Flesh Fair sequence is a good reminder of how good Spielberg is at juggling his role as both carnival barker and humanist. His movies are often dominated by trauma and violence: to appreciate his work, you just need to know when sit back and revel in an unreal, bloodthirsty spectacle, and when to avert your eyes.

Simon Abrams is a New York-based freelance arts critic. His film reviews and features have been featured in the Village Voice, Time Out New York, Slant Magazine, The L Magazine, New York Press and Time Out Chicago. He currently writes TV criticism for The Onion AV Club and is a contributing writer at the Comics Journal. His writings on film are collected at the blog, The Extended Cut. Video editor Richard Seitz has worked for 20 years as a sound designer, audio engineer, composer, and dialogue editor for video games, television, short films and theatrical trailers. Game titles include The Hulk 2, Battlestar Galactica, Van Helsing, The Hobbit, Predator and Diablo 2.