So-called “normcore fashion,” a bizarre combination of countercultural

So-called “normcore fashion,” a bizarre combination of countercultural

radicalism and bourgeois complacency, is the only way anyone has found thus far

to re-envision mainstream culture as avant-garde. In normcore culture,

twenty-something hipsters who have already established their countercultural

bona fides by dressing in the uniform of their kind for years (think

thick-rimmed glasses, skinny jeans, sportcoats, bow ties, and brogues) turn

these customs on their head by returning to the white, upper-middle class clothing

stores of their youth. Thus, a herd of excruciatingly self-aware young people seems

to dress like either their parents or their suburban peers, and outside

observers are none the wiser about their intentions. Normcore is ironic to

those who know it when they see it, and painfully earnest to those who see

someone wearing clothes from The Gap or Abercrombie & Fitch and assume it’s

the result of thoughtlessness rather than design. Of course, the more generous

view of normcore suggests that those who subscribe to its fashion wing simply

no longer wish to be distinguished from others on the basis of their attire.

Better, then, to say that the wearing of jeans and tee shirts by normcore

aficionados is merely a “detached and knowing” decision, and not necessarily an

“ironic” one. But what happens to our hipster calculus when normcore culture

goes supernatural?

Superheroes are the hipsters of English-language graphic novels: discernible

almost immediately by their accoutrements, superheros may want to be like you

and me (hence, secret identities) but before long are sure to do something—lift

a car, shoot an eye-beam—that places them outside mainstream culture. They can’t

help themselves. And millions of us read about their exploits in comic books

because we, too, can’t help ourselves. Following the adventures of costumed

counter-culturists is the nerdy equivalent of sitting on a park bench

people-watching in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn. Which is why, when

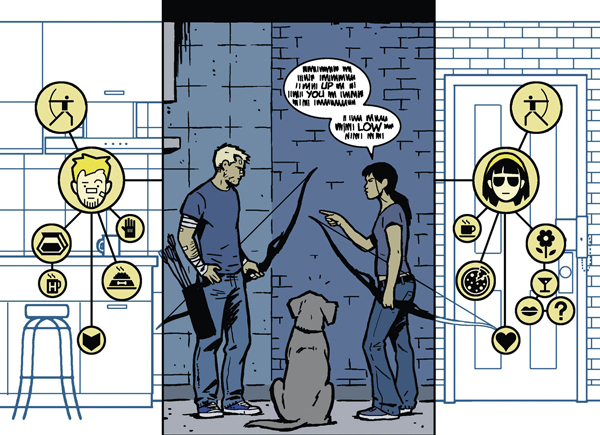

comic book writer Matt Fraction and artist David Aja decided to portray the

least-popular Avenger, Hawkeye, not as a bow-wielding badass but an

unremarkable, hoodie-wearing bro hanging around his apartment, it felt—to those

of us who enjoy comic books but are tired of their poor writing, cinema-ready

plotlines, and cutout characters—like something of a revolution.

Fraction and Aja’s Hawkeye depicts its titular character in his

traditional (at least since the Avengers movie) purple and black get-up on the

cover of its first two paperback collected editions. In both cases, “Hawkeye”/Clint

Barton—Iowan; former carnie; superpower-less master archer—is carrying his

trademark bow. It’s an intentional misdirection, as in the pages of My Life

As a Weapon (collecting Hawkeye #1-5 and Young Avengers Presents

#6) and Little Hits (collecting Hawkeye #6-11) Hawkeye rarely

uses his bow and is almost never in his Avengers uniform. Instead, he putters

about his Bed-Stuy apartment and does, well, not very much. A breakdown of the

early issues:

Hawkeye #1: Hawkeye recuperates in a hospital, adopts a dog, attends a

neighborhood barbecue, helps a single mom avoid eviction, and buys his

apartment building so he can become its landlord.

Hawkeye #2: Hawkeye practices shooting his bow, attends a gala event,

stops a gang of petty thieves (but in a tux), and has a long phone call with a

young female protégé who has a crush on him.

Hawkeye #3: Hawkeye organizes his arrows, buys a new car, sleeps with a

stranger, and fights off some heavies hired by a slumlord who wants Clint’s

apartment building back.

Hawkeye #4: Hawkeye attends a neighborhood barbecue, gets interviewed by

the Avengers, travels to the Middle East, has his wallet stolen in a taxi, and

attempts to buy at auction an item that could destroy his reputation if it

falls into the wrong hands.

And so on. Clint virtually never gets into uniform, virtually never faces a

super-villain, never uses any superpowers, and views any excitement he

experiences as a distraction from what he really wants to be doing: hanging out

with his neighbors at rooftop barbecues and petting his adopted dog (“Pizza

Dog,” so named because this iteration of Clint Barton isn’t very witty, either,

so he simply names his dog after the mutt’s favorite food). In Little Hits,

the second Hawkeye paperback collected, the low-key vibe continues, and

if anything is doubled down upon by Fraction and Aja:

Hawkeye #6: Hawkeye sets up his stereo system, saves the world from a

terrorist organization (presented, however, via just a two-page pictorial

summary), argues with the maintenance man at his apartment building, attends a

neighborhood barbecue, fights off some slumlord heavies, watches TV, and

considers going on vacation.

Hawkeye #7: Hawkeye helps a neighbor move during a hurricane, and later

rescues him from drowning in his new basement. Hawkeye’s protégé Kate Bishop

attends a wedding, goes to a pharmacy, and stops a robbery in progress.

Hawkeye #8: Hawkeye deals with a new (and crappy) romantic relationship,

tries to fight slumlord heavies but ends up in jail, and complains about his

new girlfriend messing up his comic book collection.

While the news recently came down that the Fraction/Aja Hawkeye series

will come to a close with issue #22, the fact remains that this writer-artist

duo has given us an entirely new way of thinking about not just comic books but

ourselves. There are a number of things Hawkeye does in this series that no one

without superlative archery skills could do. However, these acts of heroism are

overwhelmed in both number and vividness by the roster of things Clint Barton

does in Bed-Stuy that nearly any of us could do: make an effort to meet

and befriend our neighbors; help someone move or avoid eviction; finally unpack

our boxes and set up our new apartment; adopt a stray; or make a property

investment with an eye toward making the lives of others a little less bleak.

There’s nothing preachy about Hawkeye, however—it can’t be said that

Fraction and Aja have any evident interest in making us all better people. What

they want, I think, is no more than what Barton himself wants, and what, if we

go back into the annals of Western literature, David Copperfield once wanted:

to be the hero of our own life stories, whatever banalities and unremarkable

tribulations those stories will so often, inevitably, entail.

In other

words, Fraction and Aja have somehow captured the temperament of our Age:

neither naively fixated on the possibility of heroism nor (anymore) captivated

by anti-heroes. The earnestness of the conventional superhero has begun to irk

us, but so too, however slowly, has an unwilling and unlikely hero like

Deadpool, a mercenary whose running commentary on his own antics—droll,

fourth-wall-breaking—is steeped in petulant cynicism. In an ongoing tug-of-war

that mirrors what’s happening now in video games (cf. “#gamergate”), there’s a

divide between those who want a comic book that simply “plays well”—meaning, it

touches all the usual plot, tight-pant, and monologing-baddie bases—and one

that is reflexive enough about its aesthetics and ambitious enough about its

aims to qualify as Art. Fraction and Aja have given us a comic book series that’s

decidedly in the middle in all particulars—even its interior art is somehow,

despite its stylishness, understated—and in doing so find a sweet spot that’s

exactly where most of us already live. This new Clint Barton is neither a hero

nor an anti-hero, he’s simply . . . unremarkable. Which makes him as

remarkable a superhero as we’ve seen in a very, very long time.

Seth Abramson is the author of three collections of poetry, most recently Thievery (University of Akron Press, 2013). He has published work in numerous magazines and anthologies, including Best New Poets, American Poetry Review, Boston Review, New American Writing, Colorado Review, Denver Quarterly, and The Southern Review.

A graduate of Dartmouth College, Harvard Law School, and the Iowa

Writers’ Workshop, he was a public defender from 2001 to 2007 and is

presently a doctoral candidate in English Literature at University of

Wisconsin-Madison. He runs a contemporary poetry review series for The Huffington Post and has covered graduate creative writing programs for Poets & Writers magazine since 2008.

(Warning: This article contains spoilers for the film Iron Man 3.)

(Warning: This article contains spoilers for the film Iron Man 3.)