It takes a special talent to make us uncomfortable. Inundated with obnoxious reality television,

It takes a special talent to make us uncomfortable. Inundated with obnoxious reality television,

sensationalistic twenty-four hour news coverage, and a film culture that grows

louder and brasher by the day, it is all the more remarkable when an actor is

able to unsettle us. Philip Seymour

Hoffman had this talent in an abundance that verged on the indecent. That he was also one of the most subtle

actors of the twenty-first century seems paradoxical, until we realize that

only by stealth and imagination could someone manage to catch a jaded viewer

off-guard.

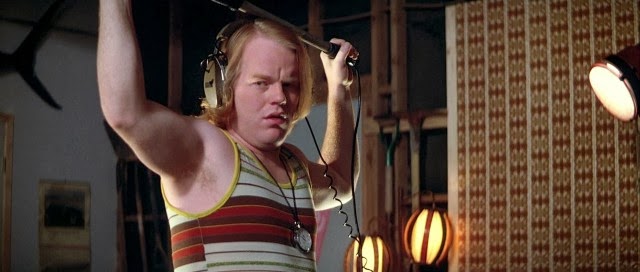

I was first caught off-guard by Hoffman in his small but

crucial role as Scotty J. in Boogie

Nights. The first appearance of this

awkward, chubby, blindingly pale presence, nervously chewing on a pen as his

belly hung out from under his childishly bright t-shirt, instantly defined this

odd but sympathetic character. When he

comes on to Dirk Diggler, I cringed in anticipation of a violent rebuff. But Diggler turns him away with a firmness

tempered by kindness, and somehow this makes the scene all the more painful and

awkward. What follows is to me one of

the most memorable moments in contemporary film, when Hoffman’s character

crumbles into self-loathing, repeating “I’m a fucking idiot!” while sobbing

pitiably. Director Paul Thomas Anderson

lets this go on for a disturbingly long time, until Hoffman’s performance

begins to verge on self-parody. I

remember the audience starting to laugh, then going silent, then laughing

again, uncomfortable, not knowing how we were supposed to react. In subsequent years Hoffman would take us to

this unsettling place, over and over again.

Hoffman never gave a bad performance: I can’t imagine any

other actor of whom one can say this without hyperbole. More importantly, though, he never gave a

performance that was anything less than fascinating. Every time he took on a new role, it felt

like he was reinventing the art of acting itself. The characters he created were never people

you could relate to: they were wildly imaginative creations that made you think

about human beings differently. Who else

could have created the heavy-breathing compulsive masturbator of Happiness, and who else could have made

him a (sort of) sympathetic character? It’s that “sort of” that was Hoffman’s

unique gift: all his characters, however minor, filled the screen, but there

was always something elusive, furtive about them. Even the kindly hospice caregiver in Magnolia is imbued with a certain

strangeness, his saintly self-effacement before Jason Robards’ meanness verging

on the masochistic.

Finding a character’s motivation is central to the practice

of acting, but Hoffman’s unique talent was for hiding that motivation from the

viewer. What drives The Master? Why is Dean

Trumbell so obsessed with taking revenge in Punch

Drunk Love? How does Capote feel

about Perry Smith? This furtiveness is what makes his performance in Doubt such compelling viewing; doubt, uncertainty, unease was what Hoffman did best. Even at his most brash, as in his brilliant

creation of Freddy in The Talented Mr.

Ripley, he turns what could have been a caricature of an obnoxious society

boy into a study in psychological complexity. Yet while Hoffman was always unerringly precise, he never seemed

studied. Each new creation seemed

effortless, and that was part of what made his characters so marvelously

strange.

It will be hard not to think of the tragic circumstances of

his death as we go back and watch the wealth of astonishing performances he

left us, but I hope we can let his characters lead their own, peculiar lives,

without Hoffman’s biography intruding on them. What made Hoffman utterly unique was his imagination, and like the

creations of a great novelist, his characters will continue to lead their unfathomable

lives, a little beyond our reach. Though

it is crushing to realize we will have no new performances from this actor who,

by all signs, was just getting started, it is some consolation to know that he

will continue to surprise us and catch us off-guard, no matter how many times we

see one of his films.

Jed Mayer is an Associate Professor of English at the State University of New York, New Paltz.

For a culture obsessed with maintaining control—over our

For a culture obsessed with maintaining control—over our

Editor’s Note: This piece contains statements that could, loosely, be construed as spoilers, but honestly, they’re phrased in a way that won’t make the film any less scary, so let’s all just relax, okay? Read the piece, which is, after all, about slightly more elevated things than what’s BOO! scary in the film.

Editor’s Note: This piece contains statements that could, loosely, be construed as spoilers, but honestly, they’re phrased in a way that won’t make the film any less scary, so let’s all just relax, okay? Read the piece, which is, after all, about slightly more elevated things than what’s BOO! scary in the film.