When I

When I

started taking classes in creative writing, one of my teachers told our class

that all we had was one story we would spend our entire lives rewriting. At the

time I found the prospect of this frightening. In a home of Cuban-Jewish

refugees I had grown used to two concepts: the impermanence of material things

and the permanence of loss. Both themes were ones I strove to break away from.

I nurtured an intense fascination with born-again Christianity. There seemed

something glorious to me about the idea that you could start again, fresh in

the world, free from the past.

The longing

for rebirth is a motif, which dominates our literary imagination and our

spiritual and emotional lives. The rebirth narrative is often constructed as a

narrative of resolution. We long to read about characters who are constantly

making choices which propel their life forward and we love reading about heroes

and heroines who are brave enough to make the choices that will ultimately lead

to some kind of change. In real life we are creatures of habit. We love a

routine, because it makes an unruly universe seem manageable and safe. In

fiction we open a box in one scene and in the next we close that box for good.

In real life, we keep—consciously or subconsciously—reopening that box.

Mad Men, which at first glance seems to

be a period drama, has actually proven to be a drama that explores how every

rebirth is a repetition. When I first started watching, I’d feel a deep,

overwhelming sense of dread with every episode. Ever swig of a martini, every

suck on a cigarette, every fuck behind another spouse’s back filled me with great

anxiety. On Mad Men, no character

(except, arguably, Peggy Olson) is ever able to change, even as the world is rapidly

changing around them. Our desire to rebuild our lives is shown to be just as

much of an illusion as anything else Don Draper or Peggy or Pete Campbell tries to sell to a

client. Both Don and Betty Draper repeat patterns from their old marriage in their new

ones. The new ad agency may look different from the old ad agency, but the same

ugliness that hid beneath the surface of the old polished veneer is there under

bright lights, mod fashion and art deco design.

In many

ways, Mad Men’s insistence on denying

us the pleasure of resolution is the secret to its success and the reason so

many of us are hooked on it, despite being frustrated that nothing ever really

changes, time and time again. Repetition of experience is electric. It grounds

us in the past and connects us to the present. We think what we seek is an

experience, which is new, but what we really want to feel connected to is an

experience that makes us feel happy and safe, in a way we once felt happy and

safe before. All addictions are nurtured by our love of repetition, a need to

feel as high as we once were, as loved as we once were loved. Don’s continuous

cheating has always had a somewhat addictive quality to it. In every case Don

wants the simultaneous thrill of the new, along with the comfort of the old.

The

repetition of familiar collective memories and period fashions has always given

Mad Men a kind of warm intimacy,

which is strange because many of its most fervent viewers haven’t personally

experienced the 60s. In an article for Vanity

Fair, “You Say You Want a Devolution,” Kurt Anderson claims that this

yearning for the past is a peculiar development of the 21st century,

which he claims is a reaction to constant technological newness. In Anderson’s

view we would rather rehash the past, rather than create anything new at all. We

watch television shows that are episodic, where characters continuously revisit

experiences, and we live in the age of the remix, where we borrow snippets

from the past as a way to reinvent the present.

But, in reality, I don’t think that

our desire for repetition is anything new at all. There is something very human

about our love of patterns. Our obsession with the past is more than just

fashion. It is built into our bones. We harvest food according to different

seasons. We pray for different purposes at different times of the day and

different times of the year. Ceremonies like graduation and weddings are built

into the very fabric of our culture, in both religious and secular settings. Poets

and lyricists have long been seduced by repetition. You can find the repeated

word or line in a classic love poem, and you can find it in contemporary songs.

We sing song refrains ranging from, “Hey Jude” to “Mmm Bop.”

The repeated onomatopoeia word can be sing-songy, as in children’s

songs, or visceral and raw. Kanye West’s brutal album, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, is often about obsession and

addiction and its most brutal, harrowing lines are repeated words. When Kanye West sings “bang, bang, bang, bang, bang,” so icy and

perfectly metered, on his new album, are these words the sound of a gang-bang

or a gunshot? The more we hear a word repeated, the stranger it sounds and the

more we re-think meaning.

Anyone who

has participated in a writing workshop knows that there is a danger in treating

art as personal therapy. Often, especially for beginning writers, we do repeat

the same story over and over, until we reach the sense that we have finally get

it “right”—we’ve made sense of the motifs we were continuously drawn back

to. My writerly “coming-of-age” was no

different. In grad school most of my writing focused on two relationships: my

relationship with my mother and a romantic relationship that broke my heart in

two.

One story resolved. For months after

the relationship was over the repetition of words from my ex’s poems would

drift through my brain at odd intervals, like a song I knew all the words to,

until one day, I didn’t remember many of those words at all. At that stage I no

longer loved this person any more and it felt like what it had become: a tiny,

tender loss, wholly different than the dramatic poems I wrote when I was still

angry and passionate about a love I didn’t want to see die.

In contrast, the relationship with

my mother evolved. We learned to understand each other. I’m not sentimental by

nature. I don’t obsess over pictures. When I move I throw stuff out. My mother

is the opposite. She takes forever to get rid of anything. Whenever I go back

home, my room is a museum of me, except it isn’t a museum of me at all: it is a

museum of the girl I was when I was 15 years old. Whenever I go home I am

stunned at how much I’ve changed and how I haven’t changed at all.

Repetition reminds us of that gap within each

of us: between that part of us that stays constant and that part of us that is

willing and able to evolve. It reminds

us that if everything is ephemeral, repetition is all we have. It reminds us

there are lovers we will leave behind and mothers we will love forever.

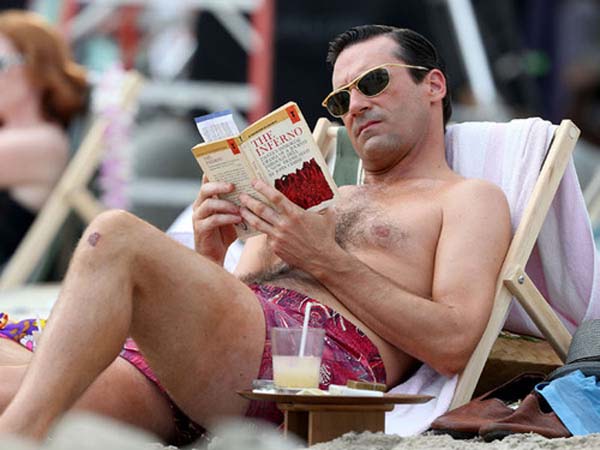

The opening image of Mad Men shows a man falling to his

death; in reality, the path down is a spiral rather than a straight line, which

means it is ultimately going to take a longer time to bottom out. This season the space between Don’s domination of

Sylvia and his tiny voiced “please” begging her to stay is getting narrower

and narrower. This season’s first Mad Men

episode opened with a scene on the beach and Don reading The Inferno. It ended with an ad that Don created: the image of

an empty beach, bare tracks in the sand, discarded clothes, the open ocean. For

Don this was an image of escape. For his clients it was an image of a suicide. Escape and suicide have always been

dangerously close throughout the series, but this season, we are reminded

over and over how it is impossible to only love the beginning of things, when

everything that begins is ultimately going to end.

Arielle Bernstein is a writer living in Washington, DC. She teaches

writing at George Washington University and American University and also

freelances. Her work has been published in The Millions, The Rumpus, St. Petersburg Review, and South Loop Review, and she has twice been listed as a finalist in Glimmertrain‘s Family Matters Short Story Contests. She is Associate Book Reviews Editor at The Nervous Breakdown.

Ride is a portrait of a very old-fashioned kind of American ethos—where being on the open road means being unattached to anyone or anything. This idea of freedom is also found in the most complex and interesting examination of masculinity in our current cultural landscape—Breaking Bad. Throughout the series, the wide, empty open expanses of the Southwest are both intoxicatingly beautiful and dangerously deserted. Men inhabit these empty highways, driving cars, dealing meth, forging alliances, and killing off their enemies. Walter White’s (Bryan Cranston) meth production is often necessarily nomadic, constantly shifting locations, from the first RV that he and his friend, partner, and former student Jesse Pinkman (Aaron Paul) use to cook, to his use of Vamanos Pest Control as a front for moving from house to house. The few times when Walt settles into a routine, as when he has a stable job cooking for kingpin Gus Fring (Giancarlo Esposito), are the times when he feels most restricted. Walt’s journey from zero to anti-hero is driven by a desire for freedom, making the series, in a sense, a beautiful ode to an America where the world is yours for the taking, where you are never under someone else’s thumb.

Ride is a portrait of a very old-fashioned kind of American ethos—where being on the open road means being unattached to anyone or anything. This idea of freedom is also found in the most complex and interesting examination of masculinity in our current cultural landscape—Breaking Bad. Throughout the series, the wide, empty open expanses of the Southwest are both intoxicatingly beautiful and dangerously deserted. Men inhabit these empty highways, driving cars, dealing meth, forging alliances, and killing off their enemies. Walter White’s (Bryan Cranston) meth production is often necessarily nomadic, constantly shifting locations, from the first RV that he and his friend, partner, and former student Jesse Pinkman (Aaron Paul) use to cook, to his use of Vamanos Pest Control as a front for moving from house to house. The few times when Walt settles into a routine, as when he has a stable job cooking for kingpin Gus Fring (Giancarlo Esposito), are the times when he feels most restricted. Walt’s journey from zero to anti-hero is driven by a desire for freedom, making the series, in a sense, a beautiful ode to an America where the world is yours for the taking, where you are never under someone else’s thumb.