Hollywood has always thrilled at its power to pluck a Lana Turner from the

soda fountain at Schwab’s, but it takes onanistic pleasure in the dark side of

its hype machine, too: how believing too much in Tinseltown’s promises can transform

nobodys into somebodies—Monroe, Harlow, Dean, and, even worse, poor

anonymous never-weres like Peg Entwhistle, the frustrated actress who

suicidally leaped off the H of the Hollywoodland sign in 1932. (Rather than die

instantly, she bled to death from a broken pelvis. This town doesn’t cut anyone

a break.)

Most movies about Hollywood’s illusion factory lie somewhere between

self-flagellatingly critical and winkingly celebratory:The Player, Sunset

Blvd.. Get Shorty, Barton Fink, Boogie Nights, Ed Wood, The Stunt Man, Singin’

In The Rain, Tropic Thunder, Bowfinger, LA Confidential. There are some

notable exceptions, such as Adaptation (reality can’t be shoehorned into

art, and certainly not into movies) or Sullivan’s Travels (legitimate pleasure

in movies is a noble pursuit), but most others hold true to playwright Wilson

Mizner’s adage that life in Hollywood is “a trip through a sewer in a

glass-bottomed boat.”

Despite its ambiguity about the Hollywood hype machine, the Academy’s

sentiments about the hard work of making art is completely unambiguous. Ray,

Shine, Precious, Atonement, Hustle And Flow—it celebrates films affirming

the redemptive power of creative craft, and how devoting oneself to its

difficult demands is a way into a better life. (Part of the 2010 Oscar Best

Picture race was between films declaring that devoting oneself to a difficult

craft will save you (The King’s Speech) vs. devoting oneself to a

difficult craft will destroy you (Black Swan). The King’s Speech

won.)

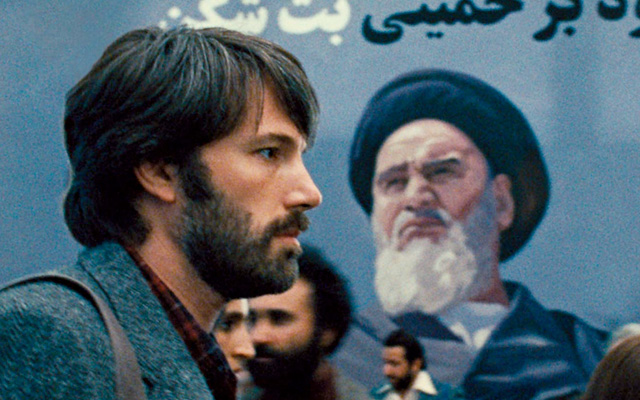

In 2012, both Silver Linings Playbook and Argo

were up for Best Picture, and any smart bettor would have fingered Silver

Linings Playbook as the shoo-in because of its “art saves all”

theme—how a recently released mental patient (Bradley Cooper) and a grieving

temptress (Jennifer Lawrence) heal themselves through ballroom dancing. Argo‘s got no art, just a bunch of hype conjured up by a CIA agent (Ben Affleck) and a pair of weary Hollywood

old-timers (John Goodman and Alan Arkin) looking to spring some hostages with a

story about a non-existent movie. “Art saves” vs. “Hype

saves” is no contest—but, strangely, the Academy didn’t see it that way.

Wink-wink movies about the illusory nature of Hollywood are nothing new. When

Gene Kelly crows at the end of Singin’ In The Rain “Stop that girl! That girl running up the aisle! That’s the

girl whose voice you heard!” it’s a moment of triumph: the illusion

factory drops its veil to celebrate the creators at the core. However, when you

drop Argo‘s veil and there’s nothing there. We’re

not even going to pretend anymore, the Academy announced. Sixty years after Singin’, Argo‘s

Best Picture win legitimized the triumph of hype over art. It announced a new

era of Hollywood sociopathy, where not even style replaces substance: lies

replace style replace substance, and you’re expected to nod and smile all the

way to the box office as your hand closes on a fistful of air.

But come on, you say, lives were saved. Doesn’t that justify a certain kind

of noble falsehood, like in 1997’s Best Foreign Language Oscar winner Life

Is Beautiful, where a father’s perverse recasting of a concentration camp

as game show enables his son to escape with hope unscathed? Or Schindler’s

List, where a German businessman conceives of a semi-truthful scheme to

save Jews in his employ? Or The Counterfeiters, where a group of

concentration camp inmates survive by making fake money? Or Jakob the Liar,

where a Jewish man keeps hope alive in the ghetto by making fabulous stories

about the messages he hears on a secret radio—and then succors the audience

with an alternate, sunnier ending?

The common denominator of all those movies is that they are Holocaust

survival stories. When Argo shamelessly borrows

that “noble falsehood” genre blueprint, it brings the same invisible

weight to a story completely unconnected to the Holocaust. It makes clear

exactly what we’re supposed to think about the movie’s Middle Eastern villains,

while deftly sidestepping any accusations of making a movie about Nazis in

keffiyeh.

But if the villains in Argo are really Nazis,

then what does that make our heroes? Argo‘s borrowing

of the “noble Holocaust deception” genre requires the appointment of

Hollywood as a sovereign Jewish nation, a connection that’s irresponsible at

best and slanderous at worst. And in addition, the surrogate Jews escape at the

end because of cunning, justifiable lies, and the illusion-casting power of

Hollywood in their back pocket—an unflattering toolkit that harkens back to

anti-Semitic canards about how Jews do business and who really runs Hollywood.

Argo is dishonest and shameful for the way it

privileges hype over art. But its willingness to cloak itself in the horror of

the Holocaust for sheer narrative convenience, as well as to milk racist

reactions on both sides of the conflict between the Jewish and Muslim worlds

for emotional resonance, proves it’s the most morally bankrupt movie to ever

win Best Picture. It’s more than dishonest. It’s dangerous, and awarding it

Best Picture showed a lack of concern about the parallels Hollywood is drawing

when we’re at war with the Middle East. Worse, it remains to be seen if

upcoming releases like Edge of Tomorrow, Elysium, or the reboot

of Robocop—all pure entertainment, none legitimized as lauding true

historical events like Argo—are going to play faster and looser with those

parallels in their own metaphorical war landscapes. And considering the

vociferous response to Argo in Iran (the movie is banned, and a feature The

General Staff is being planned as a

rebuttal), those won’t go ignored, either. The only response to the poisonous era

Argo’s Best Picture win has possibly ushered into American moviemaking is its

own oft-repeated refrain: “Argo fuck yourself.”

Violet LeVoit is a video producer and editor, film critic, and

media educator whose film writing has appeared in many publications in

the US and UK. She is the author of the short story collection I Am Genghis Cum (Fungasm Press). She lives in Philadelphia.

That's not the same thing as saying Argo is a masterpiece, though. Alexander Desplat's score leans on faux-Arabian Nights instrumentation and percussion, aural cliches that are frankly beneath a composer of his wit and passion. The script drops hints that the film will explore reality/fantasy, being/performing, but it never follows through. We see the hostages (including DuVall and Donovan) learning to play their parts, struggling with back stories and lines while Affleck “directs” them, but we never get a sense that the challenge affects them psychologically, beyond burdening them with homework while they’re trying to escape a nation in turmoil. Maybe this is a fair approach, but it’s disappointing because so often the situations and lines promise something deeper. The notions don't coalesce; they just hang there, like sub-narrative clotheslines on which deadpan one-liners can be affixed. And if director/star Ben Affleck and company were going to take liberties with the historical record—all movies do, don't mistake me for a historical literalist, please!—I wish they'd given the hostages and the Iranians one or two more good scenes to develop their personalities, maybe at the expense of all the "Tony Mendez loves his son" material, which, while sincere, didn't add much to the story or themes, and could have been deleted. (And why not cast a Latino actor in this part? Benicio Del Toro might've gotten a second Oscar if he'd starred in this.)

That's not the same thing as saying Argo is a masterpiece, though. Alexander Desplat's score leans on faux-Arabian Nights instrumentation and percussion, aural cliches that are frankly beneath a composer of his wit and passion. The script drops hints that the film will explore reality/fantasy, being/performing, but it never follows through. We see the hostages (including DuVall and Donovan) learning to play their parts, struggling with back stories and lines while Affleck “directs” them, but we never get a sense that the challenge affects them psychologically, beyond burdening them with homework while they’re trying to escape a nation in turmoil. Maybe this is a fair approach, but it’s disappointing because so often the situations and lines promise something deeper. The notions don't coalesce; they just hang there, like sub-narrative clotheslines on which deadpan one-liners can be affixed. And if director/star Ben Affleck and company were going to take liberties with the historical record—all movies do, don't mistake me for a historical literalist, please!—I wish they'd given the hostages and the Iranians one or two more good scenes to develop their personalities, maybe at the expense of all the "Tony Mendez loves his son" material, which, while sincere, didn't add much to the story or themes, and could have been deleted. (And why not cast a Latino actor in this part? Benicio Del Toro might've gotten a second Oscar if he'd starred in this.)