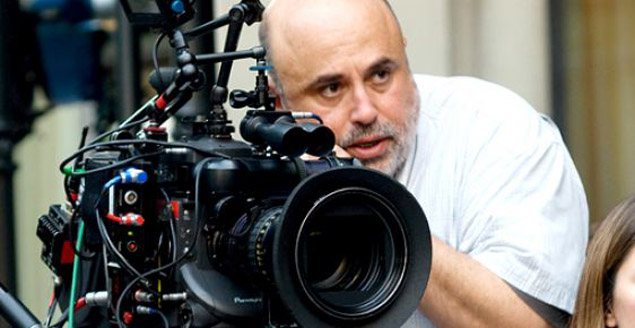

Cinematographer Harris Savides, who died on Tuesday at 55, was a poet of light. He shot some of the most stylistically striking movies of the last two decades: James Gray’s The Yards; Sofia Coppola’s Somewhere; Jonathan Glazer’s Birth; Noah Baumbach’s Greenberg; Gus Van Sant’s Elephant, Gerry and Last Days; David Fincher’s The Game and Zodiac.

Look over that list and you get a sense of his versatility. But there was more to Savides than craft. His mix of artistic restlessness and quiet confidence bridged schools of filmmaking that might seem incompatible: virtuosity and naturalism. He came out of the world of fashion and TV ads and music videos, but when you look at his feature work, you rarely get the sense that you’re being sold anything. There’s a reticence and mystery to his images, as audacious as they often are.

Birth is filled with “How the hell did they do that?” camera moves and astoundingly long takes, but his New York streetscapes and lush interiors aren’t TV-commercial glossy, or even fussed over; they seem like places where real people, not movie characters, might live and work. Coppola’s comfortably numb Somewhere has an early 70s stoner art-film vibe, but its locked-down wide shots, which let us simply watch characters behaving for minutes at a stretch, bespeak powers of concentration that Coppola’s earlier movies only hinted at. Van Sant’s hothouse triptych seems influenced by the work of hypnotically stripped-down European filmmakers who had become critical darlings in the U.S. around that time, Bela Tarr especially; but the casual-seeming quality of the light—radiant, even woozy, yet somehow not sentimentalized—is thoroughly American. Van Sant’s school-shooting psychodrama Elephant, in particular, merges documentary patience and movie-brat showiness in a way that felt strange and new; no wonder it divided critics.

In time, Fincher’s Zodiac might prove the most significant picture of the bunch. Shot digitally with the Viper camera at a time when many directors and viewers were still suspicious of high-definition video, it was at once revolutionary and reassuring. No American movie had revealed the texture of night with such crystalline clarity. At the same time, though, the mid-’70s conspiracy thriller look that Fincher and Savides devised for Zodiac’s daytime and office scenes tied the movie to analog values, and sent an important subliminal message: tools change as technology evolves, but they’re still just a means to an end.

When I heard about Savides’ passing, I reached out to Jamie Stuart, a filmmaker and writer. He’s been doing highly conceptual documentary shorts for the New York Film Festival for years now; Roger Ebert championed his 2010 short film “Idiot with a Tripod.” Stuart was an admirer of Savides’ who interviewed him twice and corresponded with him via email; an edited transcript of our conversation follows.

MZS: Harris Savides' death hit me harder than that of most cinematographers, and in trying to figure out why that was, I decided it was because he was a transitional figure in a really volatile period of film history. I can't think of many cinematographers who demonstrated such mastery of both traditional celluloid and new digital technologies.

Jamie Stuart: It's interesting. I didn't really see that as his journey so much, because I know he was very dubious of digital and greatly preferred film. I really looked at him as somebody who came from high-end fashion and music videos and commercials—but then transitioned into simplicity and naturalism.

MZS: Can you elaborate on that? Because when I think of Harris Savides, "simplicity" and "naturalism" aren't necessarily words that spring immediately to mind.

When I look over his filmography I see him acting as cinematographer on movies that seemed stylistically pivotal for their directors. He was behind the camera when Gus van Sant got into his American Bela Tarr phase, and did movie after movie comprised of very, very long Steadicam shots: Elephant, Gerry, Last Days. He was the director of photography on David Fincher's Zodiac, a groundbreaking, digitally-shot feature that revealed all the details of night that celluloid and low-end video couldn't show us before, and the somewhat stately rhythms of that movie signaled a new phase for Fincher. I wonder if the more contemplative The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and the almost live-TV-like claustrophobia of The Social Network would have happened without Fincher’s collaboration with Savides on Zodiac? We’re not talking meat-and-potatoes here. And Birth! My God. That's so daring visually that I can imagine Brian De Palma watching it and thinking, "I wouldn't have gone quite that far, but well-played, sir."

When I look over his filmography I see him acting as cinematographer on movies that seemed stylistically pivotal for their directors. He was behind the camera when Gus van Sant got into his American Bela Tarr phase, and did movie after movie comprised of very, very long Steadicam shots: Elephant, Gerry, Last Days. He was the director of photography on David Fincher's Zodiac, a groundbreaking, digitally-shot feature that revealed all the details of night that celluloid and low-end video couldn't show us before, and the somewhat stately rhythms of that movie signaled a new phase for Fincher. I wonder if the more contemplative The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and the almost live-TV-like claustrophobia of The Social Network would have happened without Fincher’s collaboration with Savides on Zodiac? We’re not talking meat-and-potatoes here. And Birth! My God. That's so daring visually that I can imagine Brian De Palma watching it and thinking, "I wouldn't have gone quite that far, but well-played, sir."

Stuart: Yes, but look at the way he shot and the way he lit a lot of those movies. When I first met him and interviewed him in 2003, he had just made Gerry and Elephant, and he found those experiences working mostly with long takes and practical light to be completely liberating. He was afraid he couldn't go back to shooting more controlled commercial work. He suggested he would feel like a caged animal.

I think that's one of the reasons Fincher brought him in on Zodiac — because he knew Harris would be able to give a natural look that also had style. Harris lit the basement scene, for instance, with 40-watt bulbs, I think. He was upset that the Viper couldn't handle low light well, so he was forced to light up a lot of scenes and stop down, when he really wanted to shoot things as they were.

MZS: Interesting. So what you're describing here is a very simple way of shooting, one that tries to make the conditions seem "available" even if they were meticulously contrived. And then on top of that you've got formal daring with regard to camera movement. That closeup of Nicole Kidman in Birth, for example, is spectacular. No pretense of being "invisible" there. You are supposed to notice the artistry. The form is the show; the hugeness of these gestures help move the film into the realm of fable, make it operatic. And yet the exteriors and interiors don't have a fussed-over look. They're inviting, real-seeming. Glazer's previous movie Sexy Beast was daring, too, in its way, but it contains nothing as stunningly, brazenly big as the stuff in Birth. Savides must have had something to do with that change, don’t you think?

MZS: Interesting. So what you're describing here is a very simple way of shooting, one that tries to make the conditions seem "available" even if they were meticulously contrived. And then on top of that you've got formal daring with regard to camera movement. That closeup of Nicole Kidman in Birth, for example, is spectacular. No pretense of being "invisible" there. You are supposed to notice the artistry. The form is the show; the hugeness of these gestures help move the film into the realm of fable, make it operatic. And yet the exteriors and interiors don't have a fussed-over look. They're inviting, real-seeming. Glazer's previous movie Sexy Beast was daring, too, in its way, but it contains nothing as stunningly, brazenly big as the stuff in Birth. Savides must have had something to do with that change, don’t you think?

Stuart: Perhaps. But I wonder how much of that is Glazer and how much of that is Harris? I think Harris would've been perfectly content to shoot everything with natural light and a perfect camera angle. Harris has a quote somewhere about lighting rooms instead of actors. And that's a very specific approach.

He hated rim light or backlight. I once spotted a close-up of Jake in Zodiac that had rim light, took a still, sent it to him convinced that had been done in a reshoot that he didn't supervise. He confirmed. I remember him going on about Ballast, and how realistic it was. He loved The Dardenne brothers.

MZS: Do you remember the first time you noticed Harris Savides' work? Do you remember when you decided he was somebody significant?

Stuart: I knew Harris' work initially from his music videos with Mark Romanek. The first one they did together was for Teenage Fanclub 20 years ago. It's black and white. Very simple. The band performing with a giant light above them.

Then, I remember when he did The Game and Fincher said he wanted Harris as his director of photography because the movie was really complex, and he needed a cameraman he could completely trust. So when I was covering the NYFF in '03, and he was there with Elephant, I introduced myself. We remained in touch ever since.

We had a similar taste in lighting and composition. We were trading e-mails when my blizzard video blew up, he was joking that I'd become a celebrity. After he first watched the video, he told me he was upset when it transitioned from black-and-white to color, but then he liked the color a lot, too, so he didn't mind.

The last time I think I saw him was at a Q&A Mark Romanek did a couple of years ago. As we were leaving, I remember looking back and seeing Mark and Harris walking together like old best friends.

I can say that, strangely, he was on my mind [Wednesday] night. The New York Film Festival screened my work at Richard Pena's tribute. One of the people featured in it was Noah Baumbach, whom I subsequently bumped into while leaving. I had sent Harris a still photo I took of Noah from a shoot a couple of months ago. I thought about e-mailing him to let him know that my work looked good on the big screen and that I'd just seen Noah.

So, to be honest, I'm a little mixed today. Going from the high of having my work play last night at the NYFF, then finding out about [his death Thursday] morning.

MZS: Did you get to spend much time with him in person?

Stuart: Our relationship was primarily via e-mail. I interviewed him twice. Once in 2003, then again in 2006 before the release of Zodiac. We randomly discussed getting together to shoot some stills or maybe my tagging along when he was first testing the Alexa [motion picture camera]—but neither materialized.

MZS: What, specifically or generally, do you think you learned from Harris Savides as an artist? Are there any things he inspired you to do, or to do better, or differently?

Stuart: He inspired me in the sense that I always sent him my work—and considering how highly I thought of him, I damn well hoped my work would be good enough to show him. He was somebody, a professional, who was there for me as I was embarking on my filmmaking career. And that's something I'm grateful for.

I remember sending him a copy of my first full mini-DV short in early 2004, made for like $50, and he told me his hat was off to me for doing so well with such little money. We thought similarly about lighting and composition. He had a very no-bullshit attitude about work. Whenever he made a movie and I offered my opinion, he always wanted it straight, even if I didn't like it.

He was somebody I always sent links of my work to. I liked his opinion. You know? I liked him. I liked his work.

Nelson Carvajal is an independent digital filmmaker, writer and content creator based out of Chicago, Illinois. His digital short films usually contain appropriated content and have screened at such venues as the London Underground Film Festival. Carvajal runs a blog called FREE CINEMA NOW which boasts the tagline: "Liberating Independent Film And Video From A Prehistoric Value System." You can follow Nelson on Twitter here.

Matt Zoller Seitz is the co-founder of Press Play.

When I look over his filmography I see him acting as cinematographer on movies that seemed stylistically pivotal for their directors. He was behind the camera when Gus van Sant got into his American Bela Tarr phase, and did movie after movie comprised of very, very long Steadicam shots: Elephant, Gerry, Last Days. He was the director of photography on David Fincher's Zodiac, a groundbreaking, digitally-shot feature that revealed all the details of night that celluloid and low-end video couldn't show us before, and the somewhat stately rhythms of that movie signaled a new phase for Fincher. I wonder if the more contemplative The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and the almost live-TV-like claustrophobia of The Social Network would have happened without Fincher’s collaboration with Savides on Zodiac? We’re not talking meat-and-potatoes here. And Birth! My God. That's so daring visually that I can imagine Brian De Palma watching it and thinking, "I wouldn't have gone quite that far, but well-played, sir."

When I look over his filmography I see him acting as cinematographer on movies that seemed stylistically pivotal for their directors. He was behind the camera when Gus van Sant got into his American Bela Tarr phase, and did movie after movie comprised of very, very long Steadicam shots: Elephant, Gerry, Last Days. He was the director of photography on David Fincher's Zodiac, a groundbreaking, digitally-shot feature that revealed all the details of night that celluloid and low-end video couldn't show us before, and the somewhat stately rhythms of that movie signaled a new phase for Fincher. I wonder if the more contemplative The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and the almost live-TV-like claustrophobia of The Social Network would have happened without Fincher’s collaboration with Savides on Zodiac? We’re not talking meat-and-potatoes here. And Birth! My God. That's so daring visually that I can imagine Brian De Palma watching it and thinking, "I wouldn't have gone quite that far, but well-played, sir." MZS: Interesting. So what you're describing here is a very simple way of shooting, one that tries to make the conditions seem "available" even if they were meticulously contrived. And then on top of that you've got formal daring with regard to camera movement.

MZS: Interesting. So what you're describing here is a very simple way of shooting, one that tries to make the conditions seem "available" even if they were meticulously contrived. And then on top of that you've got formal daring with regard to camera movement.