It seems I’ve settled into a niche. Somehow I managed to make more video essays this past year than in the five previous years combined that I’ve been doing this work. By the end of 2012, I will have produced 45 video essays for Keyframe, over three times as many as I produced for this site last year. Additionally, I produced 20 video essays forIndiewire Press Play, three forSight & Sound magazine, one for the Cinema Guild DVD of Hong Sang-soo’s The Day He Arrives, and one for the Frames Cinema Journal’s inaugural issue on film studies in the digital age. That’s seventy video essays this year, or roughly the length of a Bela Tarr film.

In the wake of all this production, I’d like to take an end-of year moment for reflection and assessment. I've singled out five videos that I consider my most representative work for Keyframe this year, examples that most vividly illustrate the kinds of issues and problems I worked through in making video essays during this period.

I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to be as focused on this little subgenre of film criticism, to better understand its properties, explore its possibilities, and develop some principles for my own practice. This process benefitted greatly from many conversations and collaborations with a host of people who are also engaged with the video essay form, including: Jonathan Marlow and Susan Gerhard at Fandor; Matt Zoller Seitz, Ken Cancelosi and Max Winter at Indiewire Press Play; Nick Bradshaw at Sight & Sound; Catherine Grant at Film Studies for Free and curator of the indispensable video essay channel Audiovisualcy; Ryan Krivoshey at Cinema Guild; fellow video essayists Matthias Stork and Steven Boone; Michał Oleszczyk, who invited me to present video essays at the OFF Plus Camera in Krakow;Roger Ebert; Jonathan Rosenbaum; Nicole Brenez; Ignatiy Vishnevetsky; and Michael Baute and Volker Pantenburg, two of the most passionate advocates of essayistic cinema and who especially have opened my eyes to its history of treasures.

Special mention goes to Nelson Carvajal, a young filmmaker with tremendous enthusiasm for video essays and who produced a couple for Keyframe (Re-Opening Greenaway’s Windows and Damon Packard: Modern Underground Horror Awaits) while I was busy getting married, the other big production of my year.

Five Personal Favorites:

In some ways this work embodies what I think is the most soundly fundamental approach to the video essay: hard observation of factual detail that gradually and naturally builds towards greater insights on the film in question and on cinema as a whole. Over the course of the year I’ve become less interested in video essays based on a pre-written script, at the same time that this mode is seeming to become the default. These types of videos play like a paper being read aloud while video clips roll like background filler (I call this the “video wallpaper” or “decorating with video” technique). Film criticism has been a slave to text long enough; isn’t the point of the video essay to re-engage it directly with the cinematic medium? If so, then words need to spring from images, not the other way around.

With this video, I started off with no idea what I wanted to say about these two films, Lady Chatterley and In the City of Sylvia, just a vague notion that they both shared the theme of love, the motif of looking and a highly sensual audiovisual texture (one that prompted me to use a non-voiceover narration so as to preserve those sounds). They’re also the kinds of films that give the viewer time and space to reflect on how one is reacting to them, which produces the experiential account detailed in this video. Perhaps then, this is the video essay at its most organic.

Matt Porterfield and the Art of the Question

Another instance of concrete observation leading to insights, now with an auteurist bent. I’ve read comments about how today’s criticism is too auteur-centric, and the most popular video essays are no exception. But auteurism is still valuable if there’s something illuminating to be learned from it, whether for viewers or even for the filmmaker. From what I understand, Matt Porterfield didn’t know his first two films Hamilton and Putty Hill were full of so many questions until he saw this video essay (at least that’s what I recall him saying on Twitter). In turn, engaging with his films helped me find a really effective hook for kicking off a video – start with a question. (Or five.) And using supercut techniques to line up the questions like dominoes is always fun.

As mentioned above, I’ve become wary of too much dependence on elements like script and narration; at the same time, I am increasingly drawn to the notion of being able to have images speak for themselves. But this has proven to be much more challenging than the standard voiceover-and-clips method, which is why I’ve done it only rarely. This video offers five different approaches to this problem, while also trying to wrest spectatorial control of the image from the most controlling and manipulative director of our time.

Mapping the Long Take: Bela Tarr and Miklós Jancsó

Seeking alternative methods of exploring images inevitably leads to the creation of new images. Looking for a way to graphically depict and explore the cinematography of two Hungarian masters led to me creating some basic maps in Power Point and moving a camera icon over them using keyframe animation in Final Cut. I refined these techniques later for the video essay exploring cinematography in Paul Thomas Anderson’ s films.

100 Masters of Animated Short Films

On the surface, compilation videos like this one, as well as Abraham Lincoln in Movies in TV and 50 Essential Chinese Movies seem like a pretty cut-and-dried order of simply gathering and arranging clips. But for each of these videos, this process resulted in some of the most time-consuming projects of the year: finding each clip, honing it to the few seconds that worked best in the montage, creating a rhythm. Still, there is great pleasure in watching as the sequence builds and reveals itself. While creating these videos don’t require as much critical thinking as writing a script from scratch, there is a critical line that emerges through montage, as the images engage with each other in dialogue (historical in the Abe Lincoln and Chinese videos; aesthetic in all three).

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining is not generally considered a family picture, but it is certainly one of the most brutally honest films ever made about the nature of family relationships. I discovered this when seeing the film for the first time with my father when I was fourteen. My father took me to dozens of R-Rated films when I was growing up, which reflected, I think, his trust in my maturity rather than any negligence about what was morally appropriate for children (though there was some of that too). Many of my fondest memories of my father involve going to the movies, and going to R-Rated films was something we usually did together, without my Mom or my sister. For two guys who hated sports, this was our equivalent of playing catch. We’d seen plenty of horror films together, but I never anticipated that a horror film would hit quite so close to home as The Shining.

Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining is not generally considered a family picture, but it is certainly one of the most brutally honest films ever made about the nature of family relationships. I discovered this when seeing the film for the first time with my father when I was fourteen. My father took me to dozens of R-Rated films when I was growing up, which reflected, I think, his trust in my maturity rather than any negligence about what was morally appropriate for children (though there was some of that too). Many of my fondest memories of my father involve going to the movies, and going to R-Rated films was something we usually did together, without my Mom or my sister. For two guys who hated sports, this was our equivalent of playing catch. We’d seen plenty of horror films together, but I never anticipated that a horror film would hit quite so close to home as The Shining. We learn during Jack’s interview that the Torrances have just moved to Colorado from Vermont, but it is not until a pediatrician is called in to check on Danny after he experiences a blackout that we learn more of the details of their past life. During this interview the camera focuses on Wendy, as she awkwardly describes to the doctor how Jack once dislocated his son’s shoulder in a fit of drunken rage. The violence of the event is masked by Shelley Duvall’s nervous smile and chirpy voice, her forced cheeriness deflecting the viewer’s empathy. The alleged “happy ending” to the story, that Jack quit drinking as a result of this incident and hasn’t had a drink for five months, is further undercut when we shift from Wendy’s face to that of the doctor, who looks frankly horrified. The camera resumes its deep focus, isolating Wendy from the doctor by framing them on either side of a series of bookshelves with the books arranged in a nervous zigzag. While today we might expect a call to Child Protective Services, in the world of The Shining such confessions only serve to further isolate the family.

We learn during Jack’s interview that the Torrances have just moved to Colorado from Vermont, but it is not until a pediatrician is called in to check on Danny after he experiences a blackout that we learn more of the details of their past life. During this interview the camera focuses on Wendy, as she awkwardly describes to the doctor how Jack once dislocated his son’s shoulder in a fit of drunken rage. The violence of the event is masked by Shelley Duvall’s nervous smile and chirpy voice, her forced cheeriness deflecting the viewer’s empathy. The alleged “happy ending” to the story, that Jack quit drinking as a result of this incident and hasn’t had a drink for five months, is further undercut when we shift from Wendy’s face to that of the doctor, who looks frankly horrified. The camera resumes its deep focus, isolating Wendy from the doctor by framing them on either side of a series of bookshelves with the books arranged in a nervous zigzag. While today we might expect a call to Child Protective Services, in the world of The Shining such confessions only serve to further isolate the family.

Several years ago, I was delighted to discover how well The Shining works as a Christmas ghost story, when my wife and I were spending the holiday with her family. After Christmas dinner we got into a conversation about times when we’d been snowbound, and this led us gradually to a discussion of Kubrick’s film. We reminisced on favorite scenes while sipping hot toddies, until we all agreed that watching this would be much more entertaining than our traditional viewing of A Christmas Carol. Just as the cold outside makes the warmth inside more welcoming, so the vision of a family tearing itself apart onscreen makes one feel closer to the family on the couch. Jack Nicholson’s malignly comic performance provides just the right sense of dangerous hilarity, heightening the sense of camaraderie, and the whole family can cheer at the end as Danny ingeniously escapes his father’s pursuit and reunites with his mother. It’s easy to forget, but The Shining actually does have a happy ending.

Several years ago, I was delighted to discover how well The Shining works as a Christmas ghost story, when my wife and I were spending the holiday with her family. After Christmas dinner we got into a conversation about times when we’d been snowbound, and this led us gradually to a discussion of Kubrick’s film. We reminisced on favorite scenes while sipping hot toddies, until we all agreed that watching this would be much more entertaining than our traditional viewing of A Christmas Carol. Just as the cold outside makes the warmth inside more welcoming, so the vision of a family tearing itself apart onscreen makes one feel closer to the family on the couch. Jack Nicholson’s malignly comic performance provides just the right sense of dangerous hilarity, heightening the sense of camaraderie, and the whole family can cheer at the end as Danny ingeniously escapes his father’s pursuit and reunites with his mother. It’s easy to forget, but The Shining actually does have a happy ending. The film has become a family tradition for us, but underneath the sense of kinship and connection with my in-laws that the film seems to foster, are more disturbing family memories. Like Jack Torrance, my father was an alcoholic, and several scenes in the film capture the experience of being the child of an alcoholic better than any film I know. In particular, I find especially troubling the scene where Danny quietly enters the chamber of his sleeping father to retrieve his toy fire engine and finds his father sitting awake on his bed. In a kind of narcoleptic daze Jack calls Danny over for a little talk. As disturbing as is Jack’s affectless attempt at speaking on a child’s level, what most troubled me about this scene when I first saw it with my father was the benumbed wariness of Danny’s responses to his father’s affection. What is most unsettling about being the child of an alcoholic is the sense of uncertainty: I never knew which version of my father I was dealing with from night to night, and this is what I saw in Danny’s response.

The film has become a family tradition for us, but underneath the sense of kinship and connection with my in-laws that the film seems to foster, are more disturbing family memories. Like Jack Torrance, my father was an alcoholic, and several scenes in the film capture the experience of being the child of an alcoholic better than any film I know. In particular, I find especially troubling the scene where Danny quietly enters the chamber of his sleeping father to retrieve his toy fire engine and finds his father sitting awake on his bed. In a kind of narcoleptic daze Jack calls Danny over for a little talk. As disturbing as is Jack’s affectless attempt at speaking on a child’s level, what most troubled me about this scene when I first saw it with my father was the benumbed wariness of Danny’s responses to his father’s affection. What is most unsettling about being the child of an alcoholic is the sense of uncertainty: I never knew which version of my father I was dealing with from night to night, and this is what I saw in Danny’s response.

I have always been drawn to visions of the future, but little did I know what brutal images were held on the Beta videocassette of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange I rented at the tender age of ten. Although the film had been banned in Great Britain, it was shelved innocently in the science fiction section of Johnny’s TV, and no one would have thought of suggesting that this might be inappropriate viewing for a child. By the time I reached the infamous scene where Alex and his droogs violently assault and rape a woman while forcing her husband to watch, I knew that I had crossed some indefinable line and that I couldn’t turn back. Later, wondering what had led me to this most disturbing of film experiences, I realized that it had all started with a filmstrip.

I have always been drawn to visions of the future, but little did I know what brutal images were held on the Beta videocassette of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange I rented at the tender age of ten. Although the film had been banned in Great Britain, it was shelved innocently in the science fiction section of Johnny’s TV, and no one would have thought of suggesting that this might be inappropriate viewing for a child. By the time I reached the infamous scene where Alex and his droogs violently assault and rape a woman while forcing her husband to watch, I knew that I had crossed some indefinable line and that I couldn’t turn back. Later, wondering what had led me to this most disturbing of film experiences, I realized that it had all started with a filmstrip.  Such primitive media technologies have a distinctive charm that, like Czech animation or natural history dioramas, is indistinguishable from their premature obsolescence. There is something poignant about the notion of watching sequences of still images in an age of television and film. I remember settling into the experience of viewing these slow-moving narratives as into a kind of meditational trance, broken occasionally by the pitch bend and warbling of stretched cassette tape. How fitting, then, that this peculiar medium would be the means of introducing me to the strange world of early electronic music.

Such primitive media technologies have a distinctive charm that, like Czech animation or natural history dioramas, is indistinguishable from their premature obsolescence. There is something poignant about the notion of watching sequences of still images in an age of television and film. I remember settling into the experience of viewing these slow-moving narratives as into a kind of meditational trance, broken occasionally by the pitch bend and warbling of stretched cassette tape. How fitting, then, that this peculiar medium would be the means of introducing me to the strange world of early electronic music. Seeing the horrific rape scene in the film left a similarly indelible impression on me, and proved to be as effective an education in the immorality of violence against women as the education the film’s protagonist experiences as part of his aversion therapy. This scene remains the image that comes to mind whenever I hear the word rape, and it gave me an early, brutal understanding of the uniquely sadistic and degrading nature of this act. If prostitution can be glibly referred to as the oldest profession, then surely rape is the oldest crime. Ironic, then, that the film I had hoped would take me into an imagined future ended up exposing me to the primitive and the barbaric.

Seeing the horrific rape scene in the film left a similarly indelible impression on me, and proved to be as effective an education in the immorality of violence against women as the education the film’s protagonist experiences as part of his aversion therapy. This scene remains the image that comes to mind whenever I hear the word rape, and it gave me an early, brutal understanding of the uniquely sadistic and degrading nature of this act. If prostitution can be glibly referred to as the oldest profession, then surely rape is the oldest crime. Ironic, then, that the film I had hoped would take me into an imagined future ended up exposing me to the primitive and the barbaric.  As a teenager I would return to the film, drawn to the stark images of a retrogressive future that seemed closer than ever. I later learned that most of the film was shot, not on sets, but in actual London settings, including Thamesmead, one of many planned urban communities of the 1960s and 1970s that produced scenarios not unlike that presented in Kubrick’s film, when families experienced traumatic feelings of disorientation as they relocated to blocks of buildings that had little in common with the neighborhoods they’d grown up in. What was an unpleasant reality for many Londoners became for me a kind of stark fantasy image, one on which I gazed obsessively in its various permutations, as seen on album covers and music videos produced by a new wave of electronic artists, like Gary Numan, John Foxx, and The Human League, composing pop music for a dark future.

As a teenager I would return to the film, drawn to the stark images of a retrogressive future that seemed closer than ever. I later learned that most of the film was shot, not on sets, but in actual London settings, including Thamesmead, one of many planned urban communities of the 1960s and 1970s that produced scenarios not unlike that presented in Kubrick’s film, when families experienced traumatic feelings of disorientation as they relocated to blocks of buildings that had little in common with the neighborhoods they’d grown up in. What was an unpleasant reality for many Londoners became for me a kind of stark fantasy image, one on which I gazed obsessively in its various permutations, as seen on album covers and music videos produced by a new wave of electronic artists, like Gary Numan, John Foxx, and The Human League, composing pop music for a dark future. Though I still deplored the violent acts of Alex and his mates, A Clockwork Orange resumed its earlier place among my obsessions. As with Alex, the film’s earlier aversion therapy didn’t take. Perhaps that’s because none of us experience only one form of social conditioning. While Alex is given nausea-inducing drugs meant to establish negative associations with the violent images on screen, his therapists clearly underestimate the staying power of his previous conditioning.

Though I still deplored the violent acts of Alex and his mates, A Clockwork Orange resumed its earlier place among my obsessions. As with Alex, the film’s earlier aversion therapy didn’t take. Perhaps that’s because none of us experience only one form of social conditioning. While Alex is given nausea-inducing drugs meant to establish negative associations with the violent images on screen, his therapists clearly underestimate the staying power of his previous conditioning.

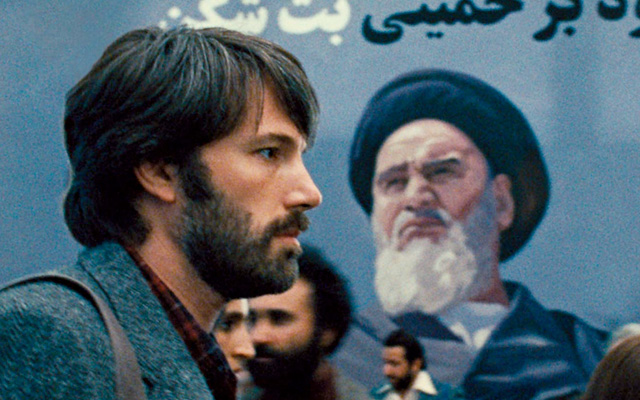

That's not the same thing as saying Argo is a masterpiece, though. Alexander Desplat's score leans on faux-Arabian Nights instrumentation and percussion, aural cliches that are frankly beneath a composer of his wit and passion. The script drops hints that the film will explore reality/fantasy, being/performing, but it never follows through. We see the hostages (including DuVall and Donovan) learning to play their parts, struggling with back stories and lines while Affleck “directs” them, but we never get a sense that the challenge affects them psychologically, beyond burdening them with homework while they’re trying to escape a nation in turmoil. Maybe this is a fair approach, but it’s disappointing because so often the situations and lines promise something deeper. The notions don't coalesce; they just hang there, like sub-narrative clotheslines on which deadpan one-liners can be affixed. And if director/star Ben Affleck and company were going to take liberties with the historical record—all movies do, don't mistake me for a historical literalist, please!—I wish they'd given the hostages and the Iranians one or two more good scenes to develop their personalities, maybe at the expense of all the "Tony Mendez loves his son" material, which, while sincere, didn't add much to the story or themes, and could have been deleted. (And why not cast a Latino actor in this part? Benicio Del Toro might've gotten a second Oscar if he'd starred in this.)

That's not the same thing as saying Argo is a masterpiece, though. Alexander Desplat's score leans on faux-Arabian Nights instrumentation and percussion, aural cliches that are frankly beneath a composer of his wit and passion. The script drops hints that the film will explore reality/fantasy, being/performing, but it never follows through. We see the hostages (including DuVall and Donovan) learning to play their parts, struggling with back stories and lines while Affleck “directs” them, but we never get a sense that the challenge affects them psychologically, beyond burdening them with homework while they’re trying to escape a nation in turmoil. Maybe this is a fair approach, but it’s disappointing because so often the situations and lines promise something deeper. The notions don't coalesce; they just hang there, like sub-narrative clotheslines on which deadpan one-liners can be affixed. And if director/star Ben Affleck and company were going to take liberties with the historical record—all movies do, don't mistake me for a historical literalist, please!—I wish they'd given the hostages and the Iranians one or two more good scenes to develop their personalities, maybe at the expense of all the "Tony Mendez loves his son" material, which, while sincere, didn't add much to the story or themes, and could have been deleted. (And why not cast a Latino actor in this part? Benicio Del Toro might've gotten a second Oscar if he'd starred in this.)