There were times not too long ago when I was not happy. Not because I was alone, which I was, or I was wasting my life, which I was, or because I was immersing myself in bad decisions, which I was. My unhappiness was easily masked. It was kept secret. I took a perverse pleasure in that secrecy. Mental illness, in my experience, takes on its own life. It becomes a tangible entity, an unwanted partner, a relationship with the self built on parasitic dependency, among other dependencies. And yet, when depression is portrayed on TV, it seems so foreign, so abstract, a caricature of what the illness really is; sometimes a literal caricature (like in BoJack Horseman or The Simpsons) and sometimes a more subtle cartoon, like in Two and a Half Men.

There were times not too long ago when I was not happy. Not because I was alone, which I was, or I was wasting my life, which I was, or because I was immersing myself in bad decisions, which I was. My unhappiness was easily masked. It was kept secret. I took a perverse pleasure in that secrecy. Mental illness, in my experience, takes on its own life. It becomes a tangible entity, an unwanted partner, a relationship with the self built on parasitic dependency, among other dependencies. And yet, when depression is portrayed on TV, it seems so foreign, so abstract, a caricature of what the illness really is; sometimes a literal caricature (like in BoJack Horseman or The Simpsons) and sometimes a more subtle cartoon, like in Two and a Half Men.

In the sitcom, depression is just another punchline. The canon is filled with scripts that mine depression for laughs. Alcoholism on Cheers or Mom, Frasier’s desperate help line callers, Two and a Half Men’s hedonism and loneliness, or years of trauma comically manifesting in the fallibility of the real world on The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, are all born of some form of depression. It’s interesting that sitcom writers can find creative ways to discuss cancer (The Big C), divorce (Louie), war (M*A*S*H), homophobia (Will & Grace), class and domestic abuse (Roseanne), race (All in the Family), or alcoholism (all of them), but examples of engaging and inventive discourse on depression are hard to find. Even on shows that feature psychotherapists, like Frasier or The Bob Newhart Show, depression is a caricature.

I’m not condemning that mode. In my writing, I’ve used my struggles with happiness as a vehicle for humour. I have found self-deprecation in discussing my own struggles cathartic. And I would imagine that’s what sitcom writers find as well—or they’re just monsters that love other people’s suffering, like Republicans or cable news.

Accurate and deft sitcom portrayals of depression may often be found in animated series. Moe the bartender’s annual suicide attempts on The Simpsons are played for laughs, but careful consideration of Moe Szyslak finds a nuanced and skilled portrait of a character struggling with mental illness. His frequent attempts at self-harm and his violent oscillation between anger and indifference are contrasted by sentimental and selfless acts like reading to sick children and a genuine and hopeful capacity for love.

Similarly, BoJack Horseman manages to discourse on despondency and emotional disorder through the filter of an anthropomorphised horse/former sitcom star with a skill live-action comedy can’t seem to muster. As a faded member of the institution that is—for the most part—incapable of balancing comedy and analysis of mental illness, the titular character (voiced by Will Arnett) in the animated Netflix sitcom tries to manage his pain through attempts to find solace and context in those around him: A pink Persian cat/agent, a freeloader, yellow Labrador Retriever/rival, and a Vietnamese-American feminist/human ghostwriter who herself is spiralling into depression. Like many manic depressives, BoJack self-medicates, and though this is certainly played for laughs, moments born of his depression lend themselves to salient and sobering moments of self-realization that are rarely found in a sitcom, like, “You know, sometimes I think I was born with a leak, and any goodness I started with just slowly spilled out of me and now its all gone. And I’ll never get it back in me. It’s too late. Life is a series of closing doors, isn’t it?” Compelling reality, straight from the animated horse’s mouth.

Animation lends itself to intelligent consideration of something so difficult and inherently personal because as an audience (and as creators) the idea of sadness can exist in the abstract. The static nature of animation in The Simpsons and BoJack Horseman provide a forum for discussion, which allows the audience to filter mental health through the transcendental. One of the most difficult aspects of depression is recognizing it, and perhaps we, as an audience, find it easier to recognize it in an anthropomorphised horse than in a mirror.

Sitcoms are not typically a place where we confront ourselves. Sitcoms love to gloss over more serious conversations when given the opportunity to use them to evolve their narratives. Depression is a walking nightmare; it’s an attempt to quiet a screaming cancer while everyone watches the tumour grow. The TV drama makes it a character flaw or a tick, often treated as an affectation or virtue. Dr. House is depressed as a result of his atrophied leg, but a genius. In Scandal, Millie becomes depressed after the death of her son, but predictably recovers. In Nashville, Juliette suffers from post-partum depression, but will inevitably return to country music stardom. In all of these cases, and so many more, depression is the result of something. It has a cause that the character can address directly. The depression is almost tangible, a character with a background story who can be operated on, prosecuted, persecuted, killed off or written out.

But depression doesn’t have a cause. It’s born of nothing. One day it just exists. There is medication, but there is no cure.

Enter Aya Cash.

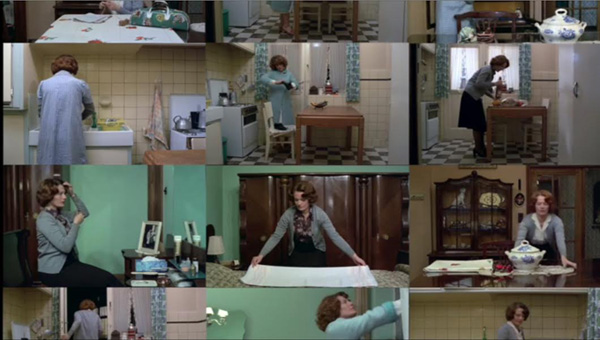

Cash’s portrayal of Gretchen’s spiralling depression in this season of You’re the Worst is nothing short of brilliant. I was an unabashed fan of the first season of the FXX sitcom, but I had concerns about how the re-imagination of the boy-meets-girl story would play out after boy (Chris Geere’s Jimmy) and girl (Cash’s Gretchen) moved in together. It seemed like the world of You’re the Worst may have had nowhere to go other than devolve into farce. And that would’ve been fine, but unspectacular and certainly unambitious—two regular traits of sitcoms seen in recent additions to the genre (Truth Be Told) or inexplicably still airing (2 Broke Girls) trading on recycled jokes and premises. But somewhere in episodes 3 and 4, the show took an unexpected turn concerning Gretchen’s clinical depression. And somehow, magically, creator Stephen Falk and his staff of writers have managed to take a serious and precious subject that the sitcom form has been mostly incapable of disseminating and used it to increase the show’s narrative scope while still being the funniest thing on TV outside of MSNBC debates.

What’s most impressive about You’re the Worst’s use of depression is that the world of the show has continued on despite Gretchen’s pain. The series hasn’t paused its narrative to focus solely on Cash’s character’s spiral—plot unrelated to her illness is still featured prominently. And therein lies the horrible truth of depression: The world doesn’t stop for it. So, while Gretchen falls apart, the universe the show has created goes on, with the characters Sunday Funday midday day drinking exploits, Lindsay’s (Kether Donohue) frozen semen, visits from Jimmy’s family and his temptations with infidelity, and Edgar’s (Desmin Borges) burgeoning relationship. While a lesser show would try to make the entire season about Gretchen, You’re the Worst instead allows her depression to exist within the show, and in so doing finds one of the most true and realistic depictions of mental illness to ever grace the small screen, and certainly the best to ever be on a sitcom.

The frustrating futility of a disease without a cure is beautifully depicted in episode 9, "LCD Soundsystem." Gretchen stalks a seemingly perfect couple, whose idyllic life she idolizes and aspires to. They have the nice house, the cute baby, the cool jobs—an aesthetic that suggests happiness and the life she believes she could have if she weren’t sick. But in a dose of reality that mimics the crushing severity and impossibility of mental illness, the couple ends up being as flawed and disappointing as Gretchen’s own existence. The husband is lecherous and desperate, hitting on Gretchen and dismissing his perfect life and family. The couple fight. The moment when she—and the audience—realize this is equally familiar and heartbreaking, while Jimmy (as many acquaintances of the depressed are) is wonderfully oblivious, and the look in Cash’s eyes in that instant are Emmy-worthy if ever a performance was. Without dialogue or animation, Gretchen’s eyes suggest a deep and resound loss, as if helplessly watching the very notion of ever being happy sink slowly into a dark and vengeful abyss

This is where the peerless brilliance of You’re the Worst’s recent season can be found. In episode 3 Gretchen misses her old "posse" and throws a party to reunite them. In episode 4 she sneaks out of the house in the middle of the night, where (we discover in episode 6) she has gone to cry alone in her car. Carelessly, and without warning, Gretchen and the audience are confronted by her depression. That violent and graceless fluctuation is perfect effigy of the sudden onslaught of mental illness. And though there will be laughter around Gretchen as the season progresses, Cash’s character exists in frightening isolation, familiar to those who have suffered from a similar affliction.

There are still a few episodes of You’re the Worst left this season, and who knows how many years of the show and its universe. I’m curious how it will deal with Gretchen’s depression and balance the tropes of the sitcom. Television is escapism. It is not the responsibility of artists to adhere to the audience’s needs. The sitcom is a form of expression, and a way of taking some small microcosm of common existence and giving those who actually exist in it a moment of solace. Cash’s performance is a caring tribute to those who suffer from mental illness, and a lesson for other sitcoms on how television can be ambitious and funny while respecting both the audience and the medium. Certainly humour may be found in dark and troubling places, but so can understanding and compassion. A well-crafted sitcom can respect its traditions—and audience—while aspiring to new modes of employing the genre.

Mike Spry is a writer, editor, and columnist who has written for The Toronto Star, Maisonneuve, and The Smoking Jacket, among others, and contributes to MTV’s PLAY with AJ. He is the author of the poetry collection JACK (Snare Books, 2008) and Bourbon & Eventide (Invisible Publishing, 2014), the short story collection Distillery Songs (Insomniac Press, 2011), and the co-author of Cheap Throat: The Diary of a Locked-Out Hockey Player (Found Press, 2013). Follow him on Twitter @mdspry.

There were times not too long ago when I was not happy. Not because I was alone, which I was, or I was wasting my life, which I was, or because I was immersing myself in bad decisions, which I was. My unhappiness was easily masked. It was kept secret. I took a perverse pleasure in that secrecy. Mental illness, in my experience, takes on its own life. It becomes a tangible entity, an unwanted partner, a relationship with the self built on parasitic dependency, among other dependencies. And yet, when depression is portrayed on TV, it seems so foreign, so abstract, a caricature of what the illness really is; sometimes a literal caricature (like in BoJack Horseman or The Simpsons) and sometimes a more subtle cartoon, like in Two and a Half Men.

There were times not too long ago when I was not happy. Not because I was alone, which I was, or I was wasting my life, which I was, or because I was immersing myself in bad decisions, which I was. My unhappiness was easily masked. It was kept secret. I took a perverse pleasure in that secrecy. Mental illness, in my experience, takes on its own life. It becomes a tangible entity, an unwanted partner, a relationship with the self built on parasitic dependency, among other dependencies. And yet, when depression is portrayed on TV, it seems so foreign, so abstract, a caricature of what the illness really is; sometimes a literal caricature (like in BoJack Horseman or The Simpsons) and sometimes a more subtle cartoon, like in Two and a Half Men.