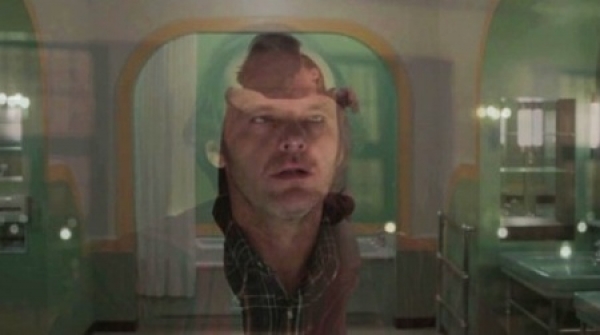

On a routine visit to the indispensible film blog Observations on Film Art, I was surprised and flattered to see that film scholar David Bordwell linked to the video essay work of myself and fellow Press Player Matt Zoller Seitz in a characteristically insightful probe of Room 237, the new feature-length film about Kubrick’s The Shining. Bordwell’s analysis uses Room 237 as a springboard to consider the practice and principles of film criticism—a topic made all the more poignant by the recent passing of Roger Ebert. We also recently published a piece by Robert Greene that regards Room 237 as a reflection of the unruly nature of the critical practice, and yesterday we published an article by Press Play regular Nelson Carvajal about his recent copyright problems with Vimeo and Disney concerning his viral Oscar video. These last two articles would seemingly have little to do with each other, but they touch on much of what I’ve been thinking about lately, with the release of Room 237 and its bearing on both online video essay works and the legacy of found footage art, as well as the contemporary practice of film criticism. I was recently interviewed by S.T. Van Airsdale on these matters for the Tribeca Film Festival website. Much of that interview went unused, so I am adapting that content here to address these issues.

It’s been intriguing to see critical and popular acclaim gather around Room 237, as smart critics praise it more that I’d expect them to. One even called it “the greatest film ever made about another film,” which is simply a gross overstatement. Even if we disqualify masterful essay films about multiple works, like Godard’s Histoire(s) du Cinema or Thom Andersen’s Los Angeles Plays Itself, even conventional behind-the-scenes docs like Lost in La Mancha or Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmakers Apocalypse are more illuminating about their single-film subject than Room 237. I’d even put Redlettermedia’s multi-part, feature-length viral YouTube takedown of Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace above Room 237 in doing a better job of skewering the obsessive nature of cinephilia, while still making smart, concrete observations on how films are actually made in reality, not just how crazily they are interpreted in people’s minds.

But if we want to talk about truly stunning reworkings of existing films, there’s Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart and Peter Tscherkassky’s Outer Space, to name just a few of the many examples to be drawn from avant garde cinema. Experimental film programmers could have a field day counter-programming Room 237 with more interesting found footage films, one of the richest veins of avant garde filmmaking: we’re talking about Bruce Conner, Matthias Muller, Martin Arnold, Les Leveque, Gustav Deutsch, Dara Birnbaum, Marlon Riggs, Black Audio Film Collective, and Leslie Thornton. Compared to these works, Room 237 amounts to a longer, slicker version of Mystery Science Theater 3000, a pseudo-intellectual minstrel show in which critical inquiry is reduced to freakish obsession. The film bears a strong anti-intellectual impulse, more geared towards ramping up the spectacular weirdness of its interviewees than towards taking their ideas seriously.

that informs it. The fact that there’s more critical and popular

interest in discussing and promoting a film like this rather than any of

the more deserving works listed above says a considerable amount about how our

collective addiction to pop culture sets the terms for what we consider

worthwhile. The fact that it’s about The Shining and Kubrick reflects an

inbred strain of cinephilia built around brand-name auteurs. As

expressed through the terminal obsessions of Room 237’s subjects, this

kind of cinephilia amounts to an oxygen-deprived hermetic practice that

takes people further into the folds of their navels, so that they don’t

have to actually engage with the world. All of the film’s seemingly

socially relevant talk of Holocaust and Native American genocide is inconsequential in terms of what one can actually do with this

insight, reducing the world-changing power of movies to a cinematic

Sunday Times crossword puzzle.

One disturbing aspect of Greene’s piece is that it conflates the

onanistic interpretations of Room 237‘s interviewees with the work of

film critics. I’d like to think that my colleagues are not trapped in

their own existential version of the Overlook Hotel. But when I try to

take the long view on contemporary film criticism and culture, I

sometimes wonder if all we’re doing each week is describing new pictures

painted on prison walls. It’s a prison not of our own making, but born out of a system that encourages us to lose ourselves inside movies as

perpetual consumers, rather than enabling us to look through, around, and

beyond them. This is especially important in grappling with the way found footage is utilized in a film like Room 237, and

to what end, given the special legacy of found footage filmmaking.

For decades, found footage and remix moving image artists have largely

toiled on the margins due to copyright issues, a marginalized status

that persists even today with YouTube and Vimeo takedown notices, as

illustrated by Nelson Carvajal’s incident. This situation leads to a

politically charged dynamic around the act of creation. It raises the

question of who really owns our culture, and who has the right to use it

to create something new and valuable, regardless of how valuable those

derivative works are deemed by the copyright owner. So much of it comes

down to challenging the hierarchy of big media culture, with its

presumed power over the average human being (what they refer to as “the

consumer”), and establishing a new paradigm of cultural fairness. The

irony with Carvajal’s work, a four-minute highlight reel of every Oscar

Best Picture winner, was that it couldn’t have been a more positive

endorsement of Hollywood product, and yet it was still taken down. This

unilateral relationship between self-appointed corporate overseers and

the rest of us brings to mind Charles Foster Kane’s espousal of “love on

my terms. Those are the only terms anybody ever knows.”

For me, Room 237 is more interesting as a commercial case study, along the same lines as Christian Marclay’s phenomenally successful art installation The Clock, a found footage work incorporating thousands of film clips into a functional, 24 hour video timepiece. The Clock has created a sensation nearly everywhere it has exhibited, including its current installation at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, where the museum’s twitter feed posts hourly wait times for viewing. Such commercially successful applications of found footage in both The Clock and Room 237 mark a distinct shift in fortunes from how found footage art has been received in the past.

For me, Room 237 is more interesting as a commercial case study, along the same lines as Christian Marclay’s phenomenally successful art installation The Clock, a found footage work incorporating thousands of film clips into a functional, 24 hour video timepiece. The Clock has created a sensation nearly everywhere it has exhibited, including its current installation at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, where the museum’s twitter feed posts hourly wait times for viewing. Such commercially successful applications of found footage in both The Clock and Room 237 mark a distinct shift in fortunes from how found footage art has been received in the past.

In that light, we can see the release of Room 237—a film deemed unreleaseable when it debuted in the festival circuit, due to copyright concerns—a more positive instance of cooperation between the rights owner and the artist. When the film amounts to a feature length commercial promoting The Shining, they would be idiots not to welcome it. Meanwhile, Christian Marclay makes half a million dollars per installation for what amounts to a 24-hour long YouTube mashup, repackaged as a blockbuster museum gallery carnival amusement. Taking this all in, I think these works have more to say about what commercial interests drive the production, programming and packaging of found footage works to fit the needs of today’s art pop market than they have to say about the art of cinema.

Still, I take heart that there are as many people out there making this work and who are simply excited to be exploring the potential of this format. I’m especially proud that it is the mission of Press Play to feature this work. At the same time, I think everyone should be aware that the cultural ramifications of this kind of creative effort inevitably become political. Unlike the lost souls in Room 237, we do not live, work or think in a vacuum. There is a system in place that influences the fates of different works, and much of it has to do with how each work serves the needs of that system. Once artists become aware of this, they see that they have a choice as far as which path they want to take and what they want their work to stand for.

Kevin B. Lee is the Editor-in-Chief of Press Play. Follow him on Twitter.

“What I believe,” he once wrote,

“What I believe,” he once wrote,

It was the same ritual every year. It was usually late October, maybe early November. You’d go to the mall where there was a bookstore, usually a Walden Books. (This was before Borders and Barnes & Noble were in every shopping center.) The section devoted to “Film” was one shelf, not a wall. You’d scan the shelf to see where it was. Then, you’d come across its brightly colored thick spine and pull it from the shelf. You’d flip through it excitedly, not being able to wait to get home and devour every page.

It was the same ritual every year. It was usually late October, maybe early November. You’d go to the mall where there was a bookstore, usually a Walden Books. (This was before Borders and Barnes & Noble were in every shopping center.) The section devoted to “Film” was one shelf, not a wall. You’d scan the shelf to see where it was. Then, you’d come across its brightly colored thick spine and pull it from the shelf. You’d flip through it excitedly, not being able to wait to get home and devour every page. And the ritual continued every year, around my birthday. Along with Leonard Maltin’s Home Video Guide, the Movie Home Companion kept me occupied when I should’ve been studying or doing my homework. Being severely visually impaired, I shouldn’t have been reading for long stretches at a time, but I did. (I remember when I discovered the Talking Book Program for the Blind had Ebert’s A Kiss is Still a Kiss on tape. I must’ve listened to it dozens of times, especially his interviews with Clint Eastwood, Lee Marvin, William Hurt, Nastassja Kinski, and Robert Mitchum, and his level-headed defense of Bob Woodward’s Wired.) Ebert’s introductions to each subsequent edition were like yearly dispatches from an old friend. He would end each intro with a list of recommended readings including Pauline Kael, Andrew Sarris, James Agee, Otis Ferguson, Stanley Kaufmann and other esteemed critics. He wasn’t insecure about having people leave him to discover other voices. He encouraged it. I devoured Kael and Sarris and Molly Haskell. I also read some John Simon. (I’m still debating if that was a good idea.) Eventually, I started seeking out different critical voices on my own. I got subscriptions to both Film Comment and Entertainment Weekly. Ebert taught me not to discriminate, so I appreciated the scholarly tone of Kent Jones and the punchy yet elegant phrasing of USA Today’s Mike Clark and EW’s Owen Gleiberman.

And the ritual continued every year, around my birthday. Along with Leonard Maltin’s Home Video Guide, the Movie Home Companion kept me occupied when I should’ve been studying or doing my homework. Being severely visually impaired, I shouldn’t have been reading for long stretches at a time, but I did. (I remember when I discovered the Talking Book Program for the Blind had Ebert’s A Kiss is Still a Kiss on tape. I must’ve listened to it dozens of times, especially his interviews with Clint Eastwood, Lee Marvin, William Hurt, Nastassja Kinski, and Robert Mitchum, and his level-headed defense of Bob Woodward’s Wired.) Ebert’s introductions to each subsequent edition were like yearly dispatches from an old friend. He would end each intro with a list of recommended readings including Pauline Kael, Andrew Sarris, James Agee, Otis Ferguson, Stanley Kaufmann and other esteemed critics. He wasn’t insecure about having people leave him to discover other voices. He encouraged it. I devoured Kael and Sarris and Molly Haskell. I also read some John Simon. (I’m still debating if that was a good idea.) Eventually, I started seeking out different critical voices on my own. I got subscriptions to both Film Comment and Entertainment Weekly. Ebert taught me not to discriminate, so I appreciated the scholarly tone of Kent Jones and the punchy yet elegant phrasing of USA Today’s Mike Clark and EW’s Owen Gleiberman.

There has been much dispute about who actually did what in the making of Poltergeist, with suggestions that Tobe Hooper’s title of director was only nominal, and that producer and co-screenwriter Spielberg was the driving creative force behind the scenes. Certainly the film would seem to have little in common with Hooper’s harrowing classic The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974): the grainy texture and ruthless violence of that film are worlds away from the lavish visual spectacles that unfold amidst the comfortable middle class settings of Poltergeist. Nevertheless, Hooper’s direction and co-authorship may be felt in the sense of menace and threat manifested from the beyond, an otherworldly place revealed to be firmly rooted in the very earth beneath the concrete and sheetrock of Cuestra Verde.

There has been much dispute about who actually did what in the making of Poltergeist, with suggestions that Tobe Hooper’s title of director was only nominal, and that producer and co-screenwriter Spielberg was the driving creative force behind the scenes. Certainly the film would seem to have little in common with Hooper’s harrowing classic The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974): the grainy texture and ruthless violence of that film are worlds away from the lavish visual spectacles that unfold amidst the comfortable middle class settings of Poltergeist. Nevertheless, Hooper’s direction and co-authorship may be felt in the sense of menace and threat manifested from the beyond, an otherworldly place revealed to be firmly rooted in the very earth beneath the concrete and sheetrock of Cuestra Verde.  The film’s totem of forgetting is the television, and the Freelings are avid worshippers. There is one in every room of the Freelings’ home, and when Carol Anne talks with “the TV People” she raises her hands to the screen as if she were one of the apes bowing before the black monolith of 2001: A Space Odyssey. The Freelings are a good family who seem to have gone slightly astray, their lives detached from the larger world outside and from the history buried beneath their feet. At night Steve and Diane (JoBeth Williams) wind down by smoking pot and watching reruns of The Twilight Zone. Tellingly, Steve is absently reading Reagan: The Man, the President, the sanctimonious biography of a public figure uniquely successful in promoting a sanitized version of progress in which American capitalism redeems the nightmares of history. While the Freelings do not commit any crimes, they are complicit in an American culture of forgetting that allows people to be bulldozed for the making of a brighter future.

The film’s totem of forgetting is the television, and the Freelings are avid worshippers. There is one in every room of the Freelings’ home, and when Carol Anne talks with “the TV People” she raises her hands to the screen as if she were one of the apes bowing before the black monolith of 2001: A Space Odyssey. The Freelings are a good family who seem to have gone slightly astray, their lives detached from the larger world outside and from the history buried beneath their feet. At night Steve and Diane (JoBeth Williams) wind down by smoking pot and watching reruns of The Twilight Zone. Tellingly, Steve is absently reading Reagan: The Man, the President, the sanctimonious biography of a public figure uniquely successful in promoting a sanitized version of progress in which American capitalism redeems the nightmares of history. While the Freelings do not commit any crimes, they are complicit in an American culture of forgetting that allows people to be bulldozed for the making of a brighter future.