Nearly ten years after his death, Marlon Brando

remains a walking alchemist’s vial of contradictions: the heavy build of a

bruiser, a brawler, a thug, that still evinces a leonine haughtiness that let

him play noblemen and generals in his prime; a quicksilver sensitivity that

flits through his most savage actions like the tail of an electric eel whipping

through dark water. And, of course, there is his handsomeness: a masculine

angularity so intense that it can’t help but invite the same worshipful scrutiny

commonly shown to the Marilyns, the Bardots, and the Lorens – which puts him,

like them, in a gilded cage of good looks, where people are reduced to their

bodies.

Though the name Brando

still evokes the memory of a time when nobody had ever seen anyone like him

before; it has also, ironically, become an adjective of choice when describing

a certain type of actor: a (usually) White, (usually) young, (always)

attractive man of great talent who will let himself be broken down over the

course of a film, who will brood and rage heroically and release a few

strategic tears before his inevitable (even if pyrrhic) triumph. Leonardo

DiCaprio is one of these actors, so is Christian Bale. Nicolas Cage was one of

these actors until he devoted his post-Oscar career to the sort of He-Man action

hero parts that Channing Tatum could sleepwalk through. When Cage does return

to the kind of rigorous roles that defined him as a capital-A actor—like his

turn as an ex-con in Joe—even the

most positive reviews lament his overall artistic decline (the headline for one

recent write-up says it best: “Joe

reminds us why we liked Nicolas Cage”). Johnny Depp literally wore a leather

jacket in one of his first classic roles; that of teen dream/gearhead hellion

Crybaby, which was, in and of itself, an homage to and a loving spoof of

Brando’s Wild One.

Each of these actors has an onscreen element stitched

together with aspects of the Brandoesque. And yet, for all of their formidable

talents, and for all of the power and ingenuity in their performances, this new

generation still doesn’t quite compare with Brando himself. The Brando standard

(which derives its definition, for my purposes, from the “young Brando’s”

persona and body of work) isn’t ultimately about swagger or artful brutishness.

It’s about vulnerability—but not the conventional vulnerability traditionally

allowed to leading men: coming gently undone in front of his love interest;

crashing hard after his mission or merger or perfect family life (or all three

at once) falls apart; surviving (barely) a brutal beating from his nemesis.

Brando’s vulnerability is rooted in what his acting teacher,

Stella Adler, defined as “his great physical beauty—not just good looks, but

that rarer thing that can only be called beauty.” That beauty is an essence

that feels as delicate and attenuated as Terry Malloy’s fingertips while he

plays with Edie’s white glove in On The Waterfront; and as elemental, as

thick with sex and need as Stanley Kowalski’s cry for his wife. “Brando took

over the vanity and posing and sheer willfulness of a good-looking woman … and

he gave it a male twist”: With these words, critic Harold Brodkey most aptly

describes the dichotomy that defines the Brando standard and gives it its

power—a tempestuous blend of what Brodkey calls “the rigorously male” with a

surrealistic kind of beauty that can’t help but call attention to itself, the

kind of beauty most associated with actresses and models, the kind of beauty

seen as a means to an end. Most of Brando’s early roles, the ones he’s most

known for, use this tension between brawn and beauty to accomplish something

extraordinarily subversive for the time of Father

Knows Best: turning the alpha male into a sex object.

Terry Malloy may be the anti-hero of On the Waterfront,

pissing away his talents as a boxer by serving as hired muscle for the mob; but

Edie, the brainy “Plain Jane” sister of the kid whose death Terry inadvertently

causes, sends the plot into motion. The heart of the film may be the arch of

Terry’s redemption, but it finds its pulse in the parallel narrative of Edie’s

sexual awakening. He’s in awe of her education, and all-too-keenly aware of his

own limitations—his bosses call him a dummy, all brawn and no brains. Edie is

the convent girl with the teaching job in her future; her belief in him gives

him a sense of legitimacy he’s incapable of finding on his own. All he can

offer her in return is his magnificent body and the promise of pleasure. Edie’s

face in the infamous glove scene, and in the scene where Terry teaches her to

drink beer, is a symphony of barely-repressed lust.

Smart, ambitious and uncompromising, Edie is the archetype

of a heroine in an early Brando film. What makes her, and all her cinematic

sisters, such as Cathy from The Wild One or

Josefina Zapata from Viva Zapata! (In

which Brando plays the late revolutionary Emiliano Zapata) so unique is that

she doesn’t particularly need

Brando’s character, but she wants

him—even though she has more promise in her pinkie finger than he has in the

sculptural bulk of his entire body. Perhaps the clearest crystallization of

this kind of relationship comes from Viva

Zapata! where Josefina teaches her peasant-born husband to read while

they’re in bed. Zapata is shirtless, his dark, muscular chest thrown into

relief by thin white sheets; our attention is called to the earthy grandeur of

his physique, but also to the emotions playing over his face—awe of the words

themselves, fear that he’ll never learn them, and shame that he’s as needy as a

child before the woman who was, moments before, in thrall to him.

Terry Malloy and Emiliano Zapata are certainly two of young

Brando’s more tender characters, but even his unabashed brutes like Stanley

Kowalski or Johnny from The Wild One embody

(quite literally) this dynamic. Stanley and Johnny are capricious beasts,

animated by instinct and chaotic whim; this gives them their erotic potency.

Stella Kowalski waxes raptly to her sister about how Stanley broke all the

lights in the house on their wedding night. She’s of the manor-born and he’s a

grease jockey; she’s vastly smarter than he is, but that doesn’t matter when he

rips his shirt off.

In The Wild One,

Cathy, the shy waitress who finds herself drawn to Johnny after his biker gang

invades her small town, doesn’t gain the same pleasure of a bare-chested

Brando; she does, however, get to hold onto him as they ride on his chopper, to

feel the engine thrum through the small of his back and the backs of his

thighs. The leather-jacketed rebel astride his Harley is an icon of American

masculinity (which Brando was arguably an architect of), but Johnny’s face

remains inscrutable, impassive; the camera holds on Cathy as desire blooms

across her features. Still, in the scene that follows, she dresses him down for

ravaging her town, calls him out on his macho bluster. All Johnny can do is sit

and listen. He knows she’s right. She’s more than right, in fact. She’s superior to him.

Many of Brando’s

supposed heirs apparent don’t allow themselves to be as similarly objectified

as he was. Like Cage or Bale, or latter-day DiCaprio, the roles they choose are

too rooted in a more conventional masculinity: These characters may possess

great depth and sensitivity, but they are, at the end of the day, cops and

superheroes, soldiers and executives who just happen to have matinee idol

looks. One could argue that Nicolas Cage’s performance in Moonstruck comes close to the Brando standard, given that his

character, Ronny, a baker who lost his hand to a bread slicer, strikes a spark

inside lonely widow Loretta. However, the friction that strikes this spark

comes from equality, not imbalance: Ronny and Loretta well-matched in intellect

and temperament; their first date is at the opera, and they first fall into bed

after one of those fights where the lovers are really parsing out who’ll be the

unstoppable force and who’ll play immovable object. Unlike Edie and Terry, or Josefina

and Emiliano, nobody is “the brain” and nobody is “the body.”

DiCaprio, who started his career as a teen heartthrob, has

transitioned away from films like Titanic

or even Total Eclipse, where his

gamine prettiness drives the movement of the film—whether that’s stirring the

heroine to abandon her posh, if constraining, lifestyle for him or driving a

legendary poet to madness and his greatest work. Some of Christian Bale’s

roles, like Bruce Wayne or Patrick Bateman, have required only a sort of

perfunctory handsomeness; a good-looking man will fit the bill, but he doesn’t

have to inspire actual lust. Indeed, the hyper-attentiveness to Bale’s

appearance in American Psycho is a

testament to his character’s soulless superficiality.

Actors like Depp or Jared Leto are almost singularly

distinguished by their prettiness—even (perhaps especially) when they take

roles meant to subvert that prettiness. Much of the press surrounding Leto’s

turn as a doomed transgender woman in Dallas Buyers Club focused on how

exquisite his features looked under his drug store make-up. Depp’s portrayal of

Edward Scissorhands has a romantic pathos, and not a horror villain’s

grotesquerie, because we know that his diamond-cutting cheekbones are under

that putty-pale skin with its constellations of scars. These actors lack that

tantalizing sense of menace inherent in the beefcake side of the Brando

standard. Could we ever imagine teen dream-era Johnny Depp breaking down Edie’s

door as Terry Malloy does, his embrace so forceful with need that he pulls them

both to the floor?

To embody the Brando standard is

become a razor’s edge, to possess a beauty that seems too fine to be dangerous,

even as it draws that first delectable lick of blood. Michael Fassbender is

making a career of dancing on that edge. In one of his first breakthrough

roles, as the cad who seduces the adolescent heroine of the film Fish Tank,

Fassbender seemingly exists to be objectified. The movie is skewed through

fifteen-year-old Mia’s perspective, and the viewer partakes of Fassbender’s

body with the same fusion of intrigue, awe, and lust that Mia feels. In an

early scene, Connor teaches her to catch fish with her hands; as he wades out

into the river, the camera holds tight on his back and we see the sculptural

planes of muscle shift under his snug t-shirt just as she does.

As Mia

watches the fish twitch and writhe inside his grasp, sunlight dapples the

water—illuminating how agile, how strong his hands are. That sun-color is

referenced again when Mia has sex with Connor: A crisp, painterly crescent of

yellow (presumably from a streetlamp outside her window) connects the side of

Mia’s cheek with Connor’s fingers, which stroke Mia’s hair. Connor is the male

equivalent of the party girl who coasts on a hard body and an easy charm; he

can’t give Mia any of the perks we’d commonly expect the December to offer the

May in that sort of affair: no hard-won wisdom, no finer things in life—just

pure bone-quaking pleasure. But there is a dark current churning under the

stream of Connor’s roguish good looks: When Mia discovers that he has a wife

and a daughter not-too-far from her age, Connor lashes out at her with the

force of a cornered snake. And yet, Mia seems as if she’s always known that

Connor had the capacity for great cruelty. Her facial expressions, post-coitus,

register equal measures relief and regret; she knows better than to do what

she’s just done. Then again, so does Stella Kowalski.

None of the sex in Shame, which is arguably the film

that Fassbender is most known for (mostly because it showcases the organ he is

most celebrated for), approaches the roughest approximation of pleasure. His

character, Brandon Sullivan, compulsively seeks out encounters that are the

equivalent of pressing his thumb into bruises hidden under his clothes. He

cycles through a coterie of call girls, Web-cam hook-ups and skin mag models;

so there is no lover whose view we can enter. The only prominent female

character, Brandon’s sister Sissy, is a sloppy jangle of raw nerve; she serves

as a mirror image of Brandon’s arctic reserve. Director Steve McQueen’s camera frames

Fassbender’s body like a museum centerpiece: We first behold him in the nude,

walking drowsily from bedroom and bathroom; everything behind him is lit in

muted hues, giving Technicolor clarity to a musculature that would make

Michelangelo weep.

Fassbender certainly possesses a Brandoesque beauty, but

he’s also got Brando’s chaotic potency. Brandon’s most pronounced moments of

self-loathing come as assaults on Sissy: The scene when he, half-naked, pins

her to the couch and screams in her face is a sort of nihilistic inverse to

Terry Malloy’s romantic door-smashing. Like Terry, Brandon is savage with need,

but his need isn’t for love or affirmation; it’s for obliteration, release.

Still, the film seems to wink at us by casting a GQ Man of the Year as a sex

addict; even as we watch Brandon debase himself with increasing abandon, we’re

tacitly asked, “Yeah, but you’d still hit that, right?”

Like Fassbender, Ryan Gosling has been branded as the

thinking woman’s sex symbol. And like Fassbender—and like Brando before

them—his handsomeness (to put it mildly) is inextricable from his onscreen

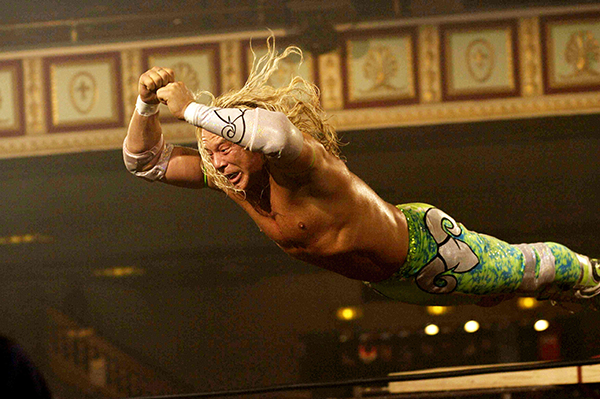

persona. The Place Beyond the Pines opens

with a close-up of Gosling’s immaculate abs as his character, a stunt rider

turned bank robber, flicks his switchblade around with an absent-minded

elegance. His lover, Romina, knows that he’s impulsive at best, violent at

worst; no good will come of him, and she’s got a better man at home. And yet,

like Edie and Stella and Cathy before her—and like every male protagonist who

has ever found himself helpless before a femme fatale—she is powerless before

the promises inherent in his sly half-smile.

Gosling’s character in Blue Valentine, Dean, has

a similar blue-collar appeal; he’s a high school dropout who, much to the

consternation of his wife, Cindy, a successful nurse, doesn’t aspire to be anything

other than a house painter. When they first meet, Cindy is an Edie, a quiet,

studious girl who comes alive under his touch. The most significant (or at

least, the most discussed) sex scene in Blue Valentine is the moment

when Dean goes down on Cindy; the focus gliding from his back and shoulders to

her rapt face. Gosling exists only as an agent and avenue of female desire; the

camera doesn’t return to him afterward, it holds on Cindy as she sighs “Oh God,

Oh God,” again and again.

Brando’s talent is a large diamond held to the sun, casting

light in an infinite array of colors. There are many other elements of his work

worth excavating and many worthy successors to that work. Idris Elba’s turn as

Stringer Bell, the wannabe kingpin who could’ve been a contender, comes

immediately to mind, as does Joaquin Phoenix’s war-wrecked vagrant in The

Master. So parsing out such a narrow standard for the Brandoesque may seem

unnecessary in a supposed golden age of acting (for men, at least), where

performers on the small and silver screen alike are challenged to renegotiate

the tropes of conventional masculinity.

But even in a time when Batman can have his back broken in a

summer blockbuster and the man in the gray flannel suit can break down in a

pivotal pitch session, male protagonists are allowed to be much more than their

appearances; and this is seen as something that gives them their heft, their

depth. Most of the actors who’ve been deemed modern-day Brandos possess degrees

of his talents and intensity, but precious few of them come close to evoking

his vulnerability. Brando’s willingness to open himself as more than just a

lover or a fighter, a rebel or a brute, but an object of lust still feels

transgressive. He is naked, even in a torn t-shirt.

Laura Bogart’s work has appeared on The Rumpus, Salon, Manifest-Station,

The Nervous Breakdown, RogerEbert.com and JMWW Journal, among other

publications. She is currently at work on a novel.

David Gordon Green has proved himself to be a remarkably flexible and unpredictable

David Gordon Green has proved himself to be a remarkably flexible and unpredictable

This

This