The

season premiere of Law & Order‘s

fourteenth season, Bodies, constituted

a departure from prior episodes. Cryptic

markings on a dead body are matched to similar markings found on a victim in

Brooklyn five years before, and then to more bodies, all of which leads

Detectives Briscoe (Jerry Orbach) and Green (Jesse L. Martin) to conclude there

is a serial killer at work in New York City. The killer—a psychopathic taxi

driver named Mark Bruner (played by guest star Ritchie Coster)—is apprehended

relatively quickly. Briscoe and Green take no actions in pursuit of the killer

that fans of the show haven’t seen a thousand times before: they canvass,

retrace the steps of the victim, happen upon a nightclub waitress with a keen

eye for creepy patrons, and finally follow a hunch that leads them to Bruner’s apartment.

It’s not the pursuit and capture that provide the climax of the episode,

however, but the legal predicament that follows: Bruner’s attorney, an idealistic

public defender, must either break attorney-client privilege—and tell the

prosecutors (and the court) where Bruner has hidden additional bodies—or be

charged as an accessory to Bruner’s crimes.

Dick

Wolf’s Law & Order debuted in the

fall of 1990, at the peak of New York’s violent crime wave—that year, there

were over 2,000 murders (compared to 333 in 2013). Law

& Order embraced the fear of social disintegration and addressed it

with a severe formalism that married esperanto liberalism with a faith in traditional

institutions of justice. The formula fit

the times. The show debuted four years

after Congress passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, which created mandatory

minimum sentences and helped inaugurate our current prison crisis, and four

years before Bill Clinton signed the Violent Crime and Law Enforcement Act (1994),

which flooded the streets with policemen and extended the death penalty to

forty new offenses. Nonetheless, by the

late 1990s, as the economy rode a wave of irrational exuberance, and NYC transitioned

from a dystopia to a destination for hipsters and financiers alike, the kinds

of crimes that captured the public imagination changed as well. Events like the

Columbine High School shootings of 1999 and the September 11, 2001 terrorist

attacks spiked fear of hidden threats from within. Over time, Wolf adapted to this changing landscape

by bringing different versions of Law

& Order to television, shifting the focus to tawdrier crimes (SVU), or quirkier detectives, (Criminal Intent).[1]

On the flagship show, however, the basic

format prevailed, with few exceptions, for the duration of its twenty-year run.

It was plug-and-play television, and its reliance on formula guaranteed the

show was almost always competent if rarely great.

In

Bodies, however, Bruner’s lack of traditional

motive—he doesn’t kill out of greed, or revenge, or jealousy—renders him

less a typical Law & Order criminal

than a force of deconstruction and illogic. When Bruner bestows knowledge of

his victims’ whereabouts on his public defender and then relies on legal rules

and ethics to preclude the attorney from sharing that information, he reveals the

fundamental contradictions between our abstract notions of justice and the

institutional rules which make the judicial system work. By using Bruner this

way, Bodies takes a cue from the modern

archetype of the fictional intelligent psychopath: the creature in Mary

Shelley’s Frankenstein. In a fit of rage, Shelley’s creature – powerful,

brilliant, and a wounded social reject all at once – frames the Frankenstein

family’s adopted daughter Justine Moritz for the murder of an infant family

member. Torn between confessing to a

crime she didn’t commit and ex-communication, Justine admits guilt and is

hanged. Although her death may be characterized as innocence lost, it’s not the

senseless destruction of innocence that drives the creature. Rather, having

been judged and excluded by society because of his appearance, the creature seeks

revenge by turning the Frankenstein family against itself and exposing the internal

contradictions and inherent arbitrariness of the justice system and, by

extension, society.

When

Law & Order premiered on NBC in

the autumn of 1990, it did so over the protests of some executives who thought

it was too intense for weekly network television. Just under twenty-five years

later, on June 6, 2013, on the same network, roughly 2.5 million viewers

watched as Hannibal‘s Dr. Abel Gideon (Eddie Izzard)

graphically disemboweled psychiatrist Dr. Frederick Chilton (Raul Esparza) while

a still-conscious Chilton looked on. Gideon is but one of fourteen serial

killers introduced in the first twenty-two episodes of Hannibal. Although notably

graphic in its violence, Hannibal is

not the first network show to focus on serial killers.[2] A non-exhaustive list includes NBC’s Profiler and Fox’s Millenium, both of which premiered in 1996. It also includes CSI, which premiered on CBS in 2000 (to be followed in 2002 by CSI: Miami and in 2004 by CSI: NY) and which, although not solely devoted

to serial killers, relied on a serial killer in its pilot and has depended on

serial killers for a number of its multi-episode narrative arcs. Criminal Minds, also on CBS and just

renewed for its tenth season, follows the FBI Behavioral Analysis Unit (the

“BAU” also featured on Hannibal)

as they track a new serial killer every week. Within months of Hannibal’s premiere in April, 2013, The

Following debuted on Fox, The Bridge

on FX, and The Killing’s third (but

first serial killer-based) season began on AMC.

And, although they are not network shows, the past year saw both the

successful initial run of HBO’s True

Detective and the disappointing conclusion of Showtime’s Dexter.

Why

the fascination with “intelligent psychopaths” and serial killers? It’s

certainly true that there’s an audience for gratuitous and/or sadistic violence.

The killers are almost invariably white men directing violence (frequently

sexual) against “helpless” victims, typically women. But there must be some further appeal, given

the fact that these shows (and novels and movies) command a large, diverse

audience of both sexes. At a minimum,

serial killer plotlines are so culturally-determined at this point that they

seem to provide a kind of generic gravity, atmosphere, and stability to any

show.[3]

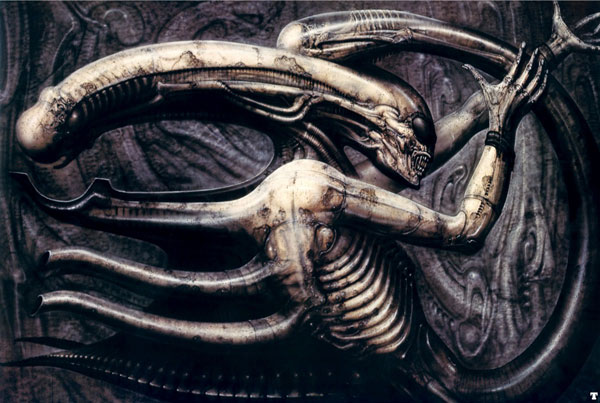

But Daniel Tiffany, in Infidel Poetics,

identifies something atavistic in our morbid fascination that dates back to the

legend of the Sphinx, the mythical creature who terrorized Thebes with a fatal

riddle. As a “liminal” creature – part human, part

lion, part eagle but not actually human, lion, or eagle – the Sphinx is both an

antecedent and ancestor to Frankenstein’s creature, whose parts also fail to

add up, leaving him at once both human and less-than-human. Both figures presage

the “intelligent psychopath” of contemporary television, whose inscrutability

is the product of his fundamental lack of that something that we believe makes us “human.” In this way,

the “riddling serial killers and

cryptographers of modernity” supply us with a “vernacular strain of

‘poetry'” and join the Sphinx (and Shelley’s creature) as authors of a

vertiginous, “apocalyptic” narrative.

These figures embody a riddle that suspends us between a “promise

of revelation” and “the threat of annihilation.”[4]

By internalizing the superficial grotesqueness of Shelley’s creature, the

serial killer is all the more beguiling because – unlike the Sphinx or the

creature – he terrorizes us from within.

If it seems a stretch to call the work of these killers poems, we need only consider how we

distinguish a killer’s “style” by what we call his signature.

It’s

not a stretch to say that our

construction and re-construction of these narratives – and the means we devise

to solve their riddles – can tell us something about a given cultural moment. Shelley’s Frankenstein,

for instance, provides a strong critique of Romantic hubris, depicting the

destructive results of our attempt to “play God” through science. Centuries later, CSI flipped Frankenstein‘s

script by suggesting a solution in science.

CSI kept in place many of the familiar

markers of the police procedural, but it also instituted a few significant

changes. Most importantly, it focused on

the analytical methods of forensic scientists who preferred to stay far away

from the action. (“I don’t chase criminals,” explains lead-scientist

Gil Grissom, “I analyze evidence.”)[5] These scientists function not only as a team,

but also as a kind of marketplace of ideas – the laboratory is collaborative but also competitive,

with the scientists vying for Grissom’s favor and sourcing solutions from a

diversity of character stereotypes including an ex-stripper, an All-American

good-old-boy, a strong-but-silently-troubled bad-ass, and geeks galore. For the

bulk of its run, the CSI method was explicitly anti-theoretical; speculation

earned a quick rebuke from Grissom. It’s not difficult to identify in early CSI a pragmatism, a belief in markets

(at least of the intellectual variety), and a fetish for technology that reflect

the Clinton era that gave birth to it. When Criminal

Minds first aired five years later, it adopted this pragmatism, down to its

team/market of diverse stereotypes, but swapped out the gleaming machinery of

the lab for behavioral models (and a dash of Big Data analysis). Criminal Minds‘ BAU also operates

collaboratively and competitively, dramatically prioritizing an internal trust

and transparency that stands in stark contradiction to the inscrutability of

the criminals they track. Both CSI and

Criminal Minds are notable for the

integral, authoritative roles they give to women. Their “marketplace”

is an inclusive one, a fact that, to a limited degree, helps off-set the

recurrent victimhood of women. Although both CSI and Criminal Minds

traffic in pop-philosophy (Criminal Minds

actually brackets its episodes with de-contextualized quotes from literature

and philosophy), neither treat serial killers as a kind of existential or philosophical

threat. Instead, the killer is merely one more problem to be solved, that can be solved, through a combination of

reason, diligence, technology, and cooperation.[6]

But

what do we make of Hannibal? It’s sui generis. It adapts characters from, but pre-dates,

Thomas Harris’s well-known novels. This means

that, to the extent it plans to follow those novels (with some, but not total,

fidelity thus far), the audience already knows a great deal about where the

narrative is going. The show centers on

Will Graham, played by Hugh Dancey, a “pure empath” who experiences crimes from

the criminal’s perspective, and Hannibal Lecter, played by Mads Mikkelsen, a

psychiatrist who has been brought in by the FBI to help Graham handle the

psychic burden of his job (and, eventually, to aid in tracking down killers). There

is no mystery for the audience to Lecter’s identity, or the fact that he is a

psychopath, a killer, and a cannibal.

Instead, the two characters face-off in a kind of dialectical opposition

as Lecter attempts to maneuver Graham into becoming a killer himself. The other

characters orbit them, occasionally changing polarities for the convenience of

the plot. Dancy’s Graham is slightly-built,

boyish, soulful, all frayed ends. Although he “teaches” criminal

profiling at the FBI training center at Quantico, the show is exceedingly light

on the analytical. You could be forgiven for wondering about the substance of

his lectures, given the fact that his “talents” are the apparent

byproduct of cognitive and psychological abnormalities. Mikkelsen’s Lecter

manages to be droll, aloof, creepy, charming, and – it must be said – a hell of

a clotheshorse. (His plaid suits and large-knotted paisley ties are a costume

designer’s dream.) He is also an unparalleled chef, a visual artist (he studied

drawing at Johns Hopkins on a fellowship), a musician and composer (harpsichord

and Theremin), a one-time neurosurgeon, and, now, a psychologist.[7] He is so refined, and his composure so total,

that it would be nice, just once, for the show to sneak up on him as he watches

television and eats cereal in sweatpants.

To

be clear, Hannibal is beautiful. And

it bears all the hallmarks of prestige television – not just the high quality

of the visuals, but also its accomplished cast and casual erudition. That said,

the show’s compositions are clearly its calling card. They are meticulous,

often daring, and Hannibal consistently

fills the screen with striking images drawn from a super-saturated palette. The most striking images are, of course, the

dead bodies themselves, and the show’s attentiveness to the

“expressive” quality of the murdered body suggests an affinity with

David Fincher’s Seven (1995).[8] No matter the killer, the dead bodies of the “victims”

are nearly always arranged and presented by the murderer in ways that blur the line

between the beautiful and the grotesque. Of the fourteen serial killers thus

far, not one has stooped to the banal depths of, say, strangling a prostitute

in a dark alley. Although the crime scenes

are elaborate, the majority of the actual murders in Hannibal occur off-screen.

Thus we “meet” most victims for the first time when they are already

dead, already posed. Only belatedly (and even then only occasionally), through

Graham’s experience of the crimes, does the audience witness any of the

brutality behind the “art.” As a result, Hannibal‘s disinterest in the victims’ interior life parallels the

disinterest of the killers themselves. Deprived of a backstory, the victims never

exist as subjects, only as the

eventual objects of the killer’s art.

That it is art that we’re seeing is reinforced again and again as the

characters “admire” the monumental design, and, yes, the “poetry”

of the “death tableaux.”

The

show is equally meticulous thematically. It maps out a symbolic universe of

mirrors and reflections, parlor rooms and libraries, sublime landscapes and

dream imagery that, in combination with the violence done to the human body, suggests

what might result if Eli Roth plucked his writers from a graduate seminar on

Lacan. That half the main characters are psychologists permits Hannibal to lay it on thick – for a show

about chasing serial killers, it spends a great deal of time listening in on

characters in book-lined rooms as they earnestly discuss psychic

“borders,” dream interpretation, and “identity.” In this

way, Hannibal shares an intellectual

ambition with both The Following and True Detective.[9] It is a credit to the creators that Hannibal manages to avoid The Following‘s too-obvious literary

aspirations. Like True Detective, it

succeeds largely in spite of itself, relying on strong visuals, charismatic

performances, and self-awareness to hide an intellectual and narrative preposterousness

that grows increasingly hard to ignore.

Hannibal incorporates the components of a modern

criminal procedural – FBI agents, gunplay, high-tech labs and the quirky

squints who occupy them – but it displays none of the other shows’ faith in (or

fetish for) methodology. On the

contrary, in the universe of Hannibal,

science is inert, ineffective, and easily manipulated. These manipulations

rarely serve as a surprise to the audience; instead, as Lecter uses forensic

evidence to frame others, send messages, or toy with the FBI, the audience is allowed

in on the joke. The wholesale

institutional haplessness of the FBI is driven home by the fact that Jack

Crawford (Laurence Fishburne), the Director of the BAU, spends most of Season

One sharing meals with Lecter in which they eat

the very victims of the crimes he’s investigating. The medical and psychology professions fare

no better. Lecter “gives” Graham encephalitis then corrupts (and then

kills) the neurologist to keep it quiet. The psychiatrist Chilton, who manages

to survive his encounter with Gideon only to be killed soon after by means of one

of Hannibal’s more elaborate strategems, is a blowhard and fraud. In the course of a couple of episodes, Lecter

manipulates both the FBI and Graham’s love interest (a psychologist consultant

to the FBI) into believing that Graham is a serial killer. Naturally, it’s also Lecter who later gets

him freed. Lecter’s ability to manipulate and escape detection is explained in Mephistopholean

and metaphysical terms by the few who recognize his dangerousness – he’s Satan,

he’s smoke, he can’t be seen. As Lecter’s psychiatrist (an excellent Gillian

Anderson) explains to him, severing their relationship before fleeing town in

fear, “I’ve had to draw a

conclusion based on what I glimpsed through the stitching of the person suit

that you wear.” That the stitching holds up as long as it does may be Hannibal‘s sole mystery.

Lecter

espouses a superficially stringent code of etiquette and ethics, and a breach

of these codes can have fatal consequences.

Like all things Hannibal,

however, this code frequently bends to his will. Although it may be Lecter’s world we’re

living in, fortune doesn’t only favor

Lecter; it favors all the killers, who always seem to finish their

“monuments,” no matter how ambitious, without any wires snapping,

without the whole Rube Goldbergian apparatus tumbling down, and without

interruption.[10] From time-to-time, Hannibal slyly concedes a universe in which psychopaths are not an

exception but rather a kind of cabal, fixing and amending its rules. “Look

at us,” the journalist Freddie Lounds (Lara

Jean Chorostecki) observes to Graham and Lecter, “a bunch of psychopaths

helping one another out.”

Still,

Lecter’s ability to manipulate the actions of others, even from remote

distances (of space and/or time) suggests not so much that he’s playing chess

while the FBI plays checkers, but rather that all of us are merely pawns in a

match he plays against himself for idle amusement. Stripped of a Sphinx-like

“fatal riddle,” the drama of Hannibal

is reduced to Lecter’s attempt to corrupt Graham. Its focus on the

“borders” that separate “us” from psychopaths suggests that

its closest relative is Showtime’s Dexter. But it lacks a central paradox like the one

that animated the first few seasons of Dexter.

There, the audience was encouraged to root for Dexter’s happiness, his

normalization. But any relationship with Dexter posed, by its very nature, a

mortal risk. As those who cared for him were endangered or killed, Dexter forced its audience to examine

its own complicity in the violence. Hannibal, on the other hand, solicits

admiration at the risk of leaving complicity unexamined. The shows share an

additional thematic similarity, however. And it’s a significant one. The

bumbling nature of the Miami police in Dexter

mirrors Hannibal’s hapless FBI;

both shows mask an inherent pessimism with a kind of “flawed hero”-worship,

suggesting a need to delegate the fight against “evil” to someone different,

and better, than us. This is not a

new trope. The transformation of Sherlock Holmes into a “high-functioning

sociopath” on Sherlock and the

emotional and intellectual volatility of Criminal

Intent’s Detective Goren are just two recent examples that suggest that the

battle against psychopaths can only be won by psychopaths. We’re watching Titans

and Olympians battle it out across the mountaintops. Or, more aptly, it’s a

comic book universe as seen through the lens of the DSM.

Nonetheless,

Hannibal can be commended for its

even-handed approach to victimhood – it has avoided the kind of unrelenting

victimization of women (victimhood is distributed across gender and race) that

plagues Criminal Minds, and that famously

drove Mandy Patinkin from the cast. It also largely avoids that show’s

uncomfortable voyeurism. But does that

discomfort have a kind of value? By hiding so much of its actual violence from

us, Hannibal often leaves the

audience with nothing but passive admiration of its technical accomplishment. Having pre-emptively emptied both science and

the law of value, it cannot offer comment or critique. Having tilted the

universe so fully in favor of its killers, Hannibal

self-limits what it can tell us about the nature of evil – banal or

otherwise – in the world off-screen.[11]

Because of this, Hannibal struggles

to justify either its graphic violence or its body count. Does it need justification? None of my

criticism detracts from the show’s direction and acting – which are excellent,

and significantly better than its kin, save perhaps for True Detective. It’s possible the wealth of surface pleasures is

enough. At one point, Graham criticizes Crawford for “mythologiz[ing] banal and cruel men who didn’t deserve

to be thought of as supervillains.”

That the show itself goes on to do exactly that suggests a winking,

Lecter-like self-awareness. In these moments

the show is most fully a reflection of the title character himself – clever,

facile, worldly, stylish, vicious, and hollow.

As the audience, we are in on the joke but denied the riddle.

Spencer Short is an attorney and author. His collection of

poetry, Tremolo (Harper 2001), was

awarded a 2000 National Poetry Series Prize. His poetry and non-fiction have

been published in The Boston Review, Coldfront, the Columbia Review, Hyperallergic,

Men’s Digest, Slate, and Verse. He lives in Brooklyn.

[1] An informal count tallied more

than three times as many serial killers in the combined twenty-five years of SVU and Criminal Intent than in the twenty years of the original Law & Order.

[2] As far back as 1988, NBC

broadcast the short-lived and before-its-time Unsub, starring Starsky &

Hutch’s David Soul as the leader of a team of FBI forensic scientists

tracking the same kinds of “unknown subjects” at issue in Criminal Minds.

[3] The

dramatic improvement in the third season of The

Killing suggests that a serial killer plotline can serve to stabilize an

ambitious, but troubled, show. In other cases, serial killers have been used to

lend “lightweight” shows a sense of substane; hence the serial killer plotlines

in lighter fare such as NCIS, Bones, and even the soap operas Loving and One Life to Live.

[4] Tiffany, Infidel Poetics (2009), p. 72.

[5] Grissom was played by William

Petersen who, coincidentally, played Will Graham in Michael Mann’s Manhunter (1986) the first adaptation from Thomas Harris’s Lecter novels.

It was remade as Red Dragon in 2002.

[6] Fox’s Bones is another example of the “empirical” procedural and is

strongly indebted to CSI.

[7] Lecter also has an exceptionally

keen sense of smell – at one point he claims to have “smelled” Graham’s encephalitis

– a trait he shares with Jean-Baptiste Grenouille, the serial killer anti-hero

of Patrick Susskind’s novel Perfume.

In Susskind’s novel, the hyperosmia is actually what drives Grenouille to kill.

[8] Twelve years later, Fincher

would again direct a film about a serial killer – this time the Zodiac – but

would focus less on the overtly apocalyptic and the graphically violent and

focus instead on the destructive internal toll that the Zodiac’s “fatal

riddle” imposed on those investigating him.

[9] It also shares significant

structural similarities to The Following

but that is beyond the scope of this piece, mostly because it would have

required watching more of The Following.

[10] Contrast all of this with the

one victim we see who manages to escape from a killer: he leaps from a bluff to

the river below only to bounce awkwardly against the rocks and plunge, already

dead, into the water.

[11] The fantastic British crime

drama The Fall (also, coincidentally,

starring Gillian Anderson) provides a welcome antidote to this self-regard. It

shares a number of structural similarities to Hannibal, but manages to capture a tension between menace and

banality that is wholly absent from Hannibal.

“You know what the meanest thing is you can say to a fat

“You know what the meanest thing is you can say to a fat

Godzilla was the megaton elephant in the room of my

Godzilla was the megaton elephant in the room of my

With any metaphor, we must read it and ourselves

With any metaphor, we must read it and ourselves