A few weeks after my video essay Chaos Cinema had been published on Press Play, I received an email from cinematographer John Bailey. Even though I am primarily invested in directors, his name was familiar to me. When I was about ten years old, my dad had shown me the Wolfgang Peterson directed Clint Eastwood vehicle In the Line of Fire (1993). I distinctly remember liking the film and watching it several times on video. When I read Mr. Bailey’s name in the email, that memory immediately popped into my head.

He told me that he would like to meet and conduct an interview with me for his work at the American Cinematographers website, where he maintains an extraordinary personal blog that I wholeheartedly recommend. I was of course quite nervous about the meeting; after all, the video essay proved to be rather controversial. But it turned out to be a wonderful experience. Mr. Bailey was very considerate and friendly and I am deeply grateful for his generous assessment of my work.

He agreed to an interview with Press Play as well. I find Mr. Bailey's thoughts on Chaos Cinema and filmmaking in general very intriguing. It is always enlightening to learn the perspective of an industry professional.

Matthias Stork: I am familiar with your work as a cinematographer, but I was unaware of your blog at the American Society of Cinematographers (ASC) website which covers a wide variety of cinephiliac topics. How did your blog come about and how do you choose topics to write about?

John Bailey: Two years ago Martha Winterhalter, publisher of American Cinematographer Magazine, asked me if I would like to contribute to the ASC website by writing a blog. I had previously written for the Filmmaker’s Forum page of the magazine. I told her that I would do it if I could write about anything I wanted to, not just film. She agreed. I saw the blog, and continue to see it, as a place where I can explore my own eclectic interests in the arts; I have no set agenda and pick subjects from books, reviews, exhibitions, and ideas from friends. Writing about a subject forces me to focus my thoughts in some kind of coherent way. I was educated by the Jesuits; I have a proclivity to want to organize seeming randomness.

In my opinion, you inhabit a rather intriguing position within the film discourse. You are both an industry professional and an observer. Does this double status inform either of your occupations?

Being a working professional may give me a more credible bully pulpit to discuss current issues. Whether or not that extends to any perspective I have on any of the other arts depends on whether the reader thinks there are any reliable aesthetic underpinnings to what I write. I try to be less categorical in my opinions on subjects other than film, as I want to intrigue the reader to explore the art and artists I write about with the same enthusiasm that prompted me to write. My perspective on cinema, however, is much more personal, and comes out of over 40 years of work. It’s really impossible to objectify any discussion about what is so close to your skin. As they say, “movies are my life.”

Being a working professional may give me a more credible bully pulpit to discuss current issues. Whether or not that extends to any perspective I have on any of the other arts depends on whether the reader thinks there are any reliable aesthetic underpinnings to what I write. I try to be less categorical in my opinions on subjects other than film, as I want to intrigue the reader to explore the art and artists I write about with the same enthusiasm that prompted me to write. My perspective on cinema, however, is much more personal, and comes out of over 40 years of work. It’s really impossible to objectify any discussion about what is so close to your skin. As they say, “movies are my life.”

In a fantastic essay titled In Search of a Cinema Canon you describe yourself as neither a critic nor a film historian, just an avid lover of movies. Could you elaborate what exactly it is that draws you to the medium? I understand that this is an abstract question. To put it differently, what do you like to see in films? Maybe we can also extend our purview and include more tangible aspects, drawn from your own work, i.e. cinematography.

If the question is abstract, my love of cinema is concrete—as is the art form itself. Wonderful as the history of experimental or abstract filmmaking is, we mostly think of movies as plot, character and narrative that relate to real world experience. It is the very real life aspect of movies that attracted me from the beginning. It may be why I have less interest in fantasy and action movies, and why I have such antipathy for gratuitously violent action films that bear no resemblance to any life experience. At the same time, I am powerfully affected by films that combine the drama of life with formalist technique and style, whether it is Bela Tarr, Robert Bresson, or Ernst Lubitsch.

I am drawn to filmmaking because though parts of me enjoy solitude, I love the give and take collaboration, even the tensions of a film set. It is a complex weave of art and technology with the equipment always threatening to overwhelm the art. You have to wrestle the equipment to the ground and make it crack to your whip.

In the essay you also mention that you and your wife, film editor Carol Littleton, were involved in an international outreach program in Kenya and Rwanda. You gave workshops on cinematography and film editing. Could you speak about your experience and how you organized the workshops?

In the essay you also mention that you and your wife, film editor Carol Littleton, were involved in an international outreach program in Kenya and Rwanda. You gave workshops on cinematography and film editing. Could you speak about your experience and how you organized the workshops?

The workshops in Nairobi were created by the German organization One Fine Day, the brainchild of Tom Twyker and others. As you might expect, it was highly structured and ran like clockwork, a classically oriented pedagogic program, including one day that featured recreating five famous paintings. There were plenty of cameras and lights to work with.

In Kigali, there was no advance program and we all tried to develop an agenda based on the experience and questions of the students, many of which were of a start-up nature. The film school is embryonic and there is virtually no support equipment such as lights and grip and dollies. The greater potential of the Rwandan program, though, lies in the tragedy of its recent genocidal history, not that that is the only theme, but the power of that cultural and societal disruption can be the spark of a greater creative force in film.

During our encounter, you told me that you went abroad as a college student, an experience to which I can fully relate. I am wondering whether the time in Europe had an impact on you which is still present, and whether it extended to your work in the film industry as well.

I think I can speak for Carol as well as for myself [when I say that] it is impossible for me to imagine a life in film had I not studied as an undergraduate in Europe. It was there that I was exposed to cinema, not just movies. It took me a long time to embrace mainstream American movies. I am still coming as a late student, courtesy of Turner Classic Movies, to the glories of many American movies of the golden studio era.

I had the great good fortune in my time as camera assistant and camera operator to work with auteurist American directors such as Monte Hellman, Robert Altman, Robert Benton, Alan Rudolph, Terrence Malick, and of course with cinematographer Nestor Almendros. It gave me an aesthetic foundation, so that when I met with Paul Schrader for American Gigolo I was able to have real discourse with him about Bresson and Antonioni.

You contacted me vis-à-vis my video essay on chaos cinema and I was very pleased to hear the opinion of a professional on the matter. You articulated your own thoughts in your blog essay but I would like to revisit some aspects of the phenomenon. How would you personally characterize what I termed chaos cinema?

You contacted me vis-à-vis my video essay on chaos cinema and I was very pleased to hear the opinion of a professional on the matter. You articulated your own thoughts in your blog essay but I would like to revisit some aspects of the phenomenon. How would you personally characterize what I termed chaos cinema?

I think that you have focused closely and clearly on action movies in discussing chaos cinema; I would characterize the notion of chaos cinema as a style that uses the camera to disrupt, disorient, even fracture the viewer’s sense of space and time—deliberately exploiting the most advanced techniques to replace traditional narrative engagement and substitute it with visceral excitement—exactly what many video games do.

Not being a huge fan of action movies, I ask myself whether the stylistic underpinnings you discuss can also be applied to more narrative oriented films and what effect chaos style has to either disrupt any sense of engagement beyond spectacle—or whether it can serve also as the foundation for a new kind of narrative. I try to address this, tentatively, in the last part of my blog essay on chaos cinema/classical cinema.

In your essay, you stress the significance of character and emotion in narrative storytelling. How do you approach these concepts as a film viewer and a cinematographer?

We can’t escape our personal histories. From grammar school forward, I was presented with many aspects of a classical education, meaning one that was based on Aristotelian ideas, even as they evolved through the pageantry of Western art history. As a viewer, I, like most people, am looking for emotional involvement that is grounded in some sense of credible experience. Those movies don’t have to be dour dramas. Sometimes, animated films like Up or The Triplets of Belleville capture these qualities in an essence that is more elusive in live action films.

As a cinematographer, I read the screenplay not for visual style or technical potential, but for emotional engagement. Any consideration of film style develops from that starting point, in discussions with the director and production designer.

You worked as a cinematographer for the film In the Line of Fire, directed by German émigré filmmaker Wolfgang Petersen. It is my favorite of his Hollywood endeavors. Could you explain how you approached your work in the film? What was important to you, and how did you translate it into the film?

You worked as a cinematographer for the film In the Line of Fire, directed by German émigré filmmaker Wolfgang Petersen. It is my favorite of his Hollywood endeavors. Could you explain how you approached your work in the film? What was important to you, and how did you translate it into the film?

I told Wolfgang that Das Boot demonstrated beyond any doubt that he is a master of action; I had confidence that the visceral momentum of the film was easy for him. What interested me more is the cat-and-mouse drama between John Malkovich and Clint Eastwood, one an angry nihilist, and the other a humanist looking for redemption. I told him that the therapy scenes in Ordinary People between Tim Hutton and Judd Hirsch constituted a film within the film. I thought the phone calls between Malkovich and Eastwood had a similar basis, and that if we could make each of the phone calls dramatic and visually compelling—the rest of the film was window dressing. You may agree or not, but that is the idea I worked from and I think that is what makes that film different from most action films.

Cinematography has undergone significant changes during the last decades. What are, for you, some of the prominent shifts that have occurred and how do they register on-screen for average audiences? What would you define as chaotic attributes of modern cinematography?

To answer that question would require several lengthy essays. The most prominent shift, I think, is out of the hands of the cinematographer and is in the hands of the VFX creators. And that is the rise of computer-generated imagery to such a level of convincing space that, at least for quick cut, short bursts, it is visually credible as reality. What usually gives it away is the hubris of the generators in defying the laws of gravity. Movie action sequences have become so usurped by the ir-reality of first person video gaming that viewers don’t believe action sequences in movies any more; they look phony. Of course, that’s no problem if you aim for nothing more than spectacle. What is phenomenal about the CGI technique is the ability to tell character driven movies such as The Curious Case of Benjamin Button in a way that was not possible before.

Chaotic attributes are simply major disruptions of time and space as a device to deconstruct or destroy traditional narrative. The use of multiple cameras for simultaneous action, especially at different frame rates, is one tool. Extensive use of multiple cameras, especially with longer lenses, disengages you from a sense of intimacy with the characters. Multiple cameras also make it more difficult to do what the French call a plan sequence, the complex interplay of one structured shot into the next one; that style is the antithesis of chaos cinema. Also, I find that shaky-cam is often a distancing rather than an engaging device. It is supposed to make you feel more involved, more present in the action. In practice, especially with arbitrary zooming and deliberately bad pans, it just throws you outside the moment making you conscious of the camerawork. It is self-indulgent and hubristic. Conversely, if you are aiming for a cinema verite feel, these very techniques can be effective. There are, after all, no set prohibitions. Also, rapid fire cutting as a relentless technique does not keep you engaged; if there is no slower paced rhythm in the quieter scenes as counter rhythmic, this pace becomes alienating, even boring. Finally, layering shot after shot after shot with no sense of hierarchy reduces the concept of cinematography to nothing but coverage. The shot becomes just data. The cinematographer is reduced to capturing data.

Chaotic attributes are simply major disruptions of time and space as a device to deconstruct or destroy traditional narrative. The use of multiple cameras for simultaneous action, especially at different frame rates, is one tool. Extensive use of multiple cameras, especially with longer lenses, disengages you from a sense of intimacy with the characters. Multiple cameras also make it more difficult to do what the French call a plan sequence, the complex interplay of one structured shot into the next one; that style is the antithesis of chaos cinema. Also, I find that shaky-cam is often a distancing rather than an engaging device. It is supposed to make you feel more involved, more present in the action. In practice, especially with arbitrary zooming and deliberately bad pans, it just throws you outside the moment making you conscious of the camerawork. It is self-indulgent and hubristic. Conversely, if you are aiming for a cinema verite feel, these very techniques can be effective. There are, after all, no set prohibitions. Also, rapid fire cutting as a relentless technique does not keep you engaged; if there is no slower paced rhythm in the quieter scenes as counter rhythmic, this pace becomes alienating, even boring. Finally, layering shot after shot after shot with no sense of hierarchy reduces the concept of cinematography to nothing but coverage. The shot becomes just data. The cinematographer is reduced to capturing data.

I have always wanted to pick the brain of a film professional about technology and the pragmatic approach to filmmaking. Could you briefly break down the profession of a cinematographer? What does a cinematographer do, and how?

This is actually easy to address. The cinematographer uses the camera to dramatize visually the narrative potential of the screenplay. His main tools to do this are lens selection, camera placement, composition, camera movement, shot-to-shot coverage, and light. In some film cultures it is the light that is his principal focus; in other cultures, such as the USA, all of these elements are the purview of the cinematographer. This work is done in collaboration with the director and in varying degrees with the production designer and costumer. Some directors are story and performance oriented; others are image oriented. The great ones should be both.

The cinematographer’s ability to do all of this work is modified or even constrained by many things, such as schedule and money. The greatest challenge for the cinematographer, like for any artist, is the ability to create good work within the parameters you have—to be flexible, to have a can-do attitude. Often it is the cinematographer and assistant director who have to set the positive tone on the set. The director is swamped by needs of the actors and dictates of the producers and studio.

You cite Point Blank as a paradigm of effective action. Are there any other action films that you like? And how would you define good action?

Good action is not an end in itself, but is a visceral tool to generate emotion by ratcheting up tension or creating release (catharsis). It serves as counterpoint to static dialogue scenes. Just like in a symphony, you have allegro and adagio movements.

I like much of Kurosawa; much of his action happens only after incredible tension precedes it. The same for the climactic action scenes in Sergio Leone films, and not just the spaghetti westerns. The Battle of Algiers and Wages of Fear are great action films, and recently, The Hurt Locker.

To hearken back to your blog, I was astonished by the breadth of topics you cover, and I urge cinephiles to seek it out. All of your work is steeped in the history of cinema. I wonder if you could enumerate a few books on film that you regard as essential to the study and enjoyment of the medium.

The books I love are not about the making of films but about life by filmmakers: Cocteau’s Diary of a Film; Bunuel’s My Last Sigh; Herzog’s Walking in Ice; Kurosawa’s Something Like an Autobiography; Jack Cardiff’s Magic Hour; Nestor Almendros’ A Man with a Camera; Karl Brown’s Adventures with D.W. Griffith; and of course, Bresson’s Notes on the Cinematographer.

If you could pick any director to collaborate with, who would it be?

The late Francois Truffaut. I only met him once, when he came to visit Robert Benton on the set of The Late Show. Of living directors, I have done five films with Paul Schrader, who has been a great presence in my life beyond the set. I have also made five films with my friend Ken Kwapis. I hope to do five more with him.

Matthias Stork is a Press Play contributor and film scholar-critic from Germany who continues to pursue an academic career at UCLA where he studies film and television. He has an MA in Education with emphasis on American and French literature and film from Goethe University, Frankfurt. He has attended The Cannes film festival twice (2010/2011) as a representitive of Goethe University's film school and you can read his blog here.

By Matt Zoller Seitz

By Matt Zoller Seitz

According to

According to

Luthor’s out of prison (thanks to the absent hero’s failure to testify at his trial) and up to his old tricks, scheming around Metropolis with his thug henchmen, his wiseass gal pal (Parker Posey) and two yippy but vicious little dogs. In Superman’s absence, Lois Lane (Bosworth, swapping stoic warmth for Margot Kidder’s abrasive ’70s kookiness) won a Pulitzer for an editorial about why the world doesn’t need him, and then settled down with Daily Planet colleague Richard White (James Marsden), nephew of publisher, Perry White (a brusque yet warm performance by Frank Langella).

Luthor’s out of prison (thanks to the absent hero’s failure to testify at his trial) and up to his old tricks, scheming around Metropolis with his thug henchmen, his wiseass gal pal (Parker Posey) and two yippy but vicious little dogs. In Superman’s absence, Lois Lane (Bosworth, swapping stoic warmth for Margot Kidder’s abrasive ’70s kookiness) won a Pulitzer for an editorial about why the world doesn’t need him, and then settled down with Daily Planet colleague Richard White (James Marsden), nephew of publisher, Perry White (a brusque yet warm performance by Frank Langella). Where most comic book movies are paradoxically inclined to make their points verbally—bulldozing heaps of raw data in our faces, a la The Matrix movies, Batman Begins and Singer’s own X-Men films — Superman Returns is conceived as a visionary spectacle, a series of mythic tableaus that brazenly liken Superman to Mercury, Jesus, Atlas and Prometheus. It’s a sensory—at times sensuous—experience, modeled not just on great comic book art, but on the crème-de-la-crème of machine-age spectacles: 2001: A Space Odyssey and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. (Warning, that segue means possible spoilers ahead.)

Where most comic book movies are paradoxically inclined to make their points verbally—bulldozing heaps of raw data in our faces, a la The Matrix movies, Batman Begins and Singer’s own X-Men films — Superman Returns is conceived as a visionary spectacle, a series of mythic tableaus that brazenly liken Superman to Mercury, Jesus, Atlas and Prometheus. It’s a sensory—at times sensuous—experience, modeled not just on great comic book art, but on the crème-de-la-crème of machine-age spectacles: 2001: A Space Odyssey and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. (Warning, that segue means possible spoilers ahead.)

Being a working professional may give me a more credible bully pulpit to discuss current issues. Whether or not that extends to any perspective I have on any of the other arts depends on whether the reader thinks there are any reliable aesthetic underpinnings to what I write. I try to be less categorical in my opinions on subjects other than film, as I want to intrigue the reader to explore the art and artists I write about with the same enthusiasm that prompted me to write. My perspective on cinema, however, is much more personal, and comes out of over 40 years of work. It’s really impossible to objectify any discussion about what is so close to your skin. As they say, “movies are my life.”

Being a working professional may give me a more credible bully pulpit to discuss current issues. Whether or not that extends to any perspective I have on any of the other arts depends on whether the reader thinks there are any reliable aesthetic underpinnings to what I write. I try to be less categorical in my opinions on subjects other than film, as I want to intrigue the reader to explore the art and artists I write about with the same enthusiasm that prompted me to write. My perspective on cinema, however, is much more personal, and comes out of over 40 years of work. It’s really impossible to objectify any discussion about what is so close to your skin. As they say, “movies are my life.” In the essay you also mention that you and your wife, film editor

In the essay you also mention that you and your wife, film editor  You contacted me vis-à-vis my video essay on

You contacted me vis-à-vis my video essay on  You worked as a cinematographer for the film In the Line of Fire, directed by German émigré filmmaker

You worked as a cinematographer for the film In the Line of Fire, directed by German émigré filmmaker  Chaotic attributes are simply major disruptions of time and space as a device to deconstruct or destroy traditional narrative. The use of multiple cameras for simultaneous action, especially at different frame rates, is one tool. Extensive use of multiple cameras, especially with longer lenses, disengages you from a sense of intimacy with the characters. Multiple cameras also make it more difficult to do what the French call a plan sequence, the complex interplay of one structured shot into the next one; that style is the antithesis of chaos cinema. Also, I find that shaky-cam is often a distancing rather than an engaging device. It is supposed to make you feel more involved, more present in the action. In practice, especially with arbitrary zooming and deliberately bad pans, it just throws you outside the moment making you conscious of the camerawork. It is self-indulgent and hubristic. Conversely, if you are aiming for a cinema verite feel, these very techniques can be effective. There are, after all, no set prohibitions. Also, rapid fire cutting as a relentless technique does not keep you engaged; if there is no slower paced rhythm in the quieter scenes as counter rhythmic, this pace becomes alienating, even boring. Finally, layering shot after shot after shot with no sense of hierarchy reduces the concept of cinematography to nothing but coverage. The shot becomes just data. The cinematographer is reduced to capturing data.

Chaotic attributes are simply major disruptions of time and space as a device to deconstruct or destroy traditional narrative. The use of multiple cameras for simultaneous action, especially at different frame rates, is one tool. Extensive use of multiple cameras, especially with longer lenses, disengages you from a sense of intimacy with the characters. Multiple cameras also make it more difficult to do what the French call a plan sequence, the complex interplay of one structured shot into the next one; that style is the antithesis of chaos cinema. Also, I find that shaky-cam is often a distancing rather than an engaging device. It is supposed to make you feel more involved, more present in the action. In practice, especially with arbitrary zooming and deliberately bad pans, it just throws you outside the moment making you conscious of the camerawork. It is self-indulgent and hubristic. Conversely, if you are aiming for a cinema verite feel, these very techniques can be effective. There are, after all, no set prohibitions. Also, rapid fire cutting as a relentless technique does not keep you engaged; if there is no slower paced rhythm in the quieter scenes as counter rhythmic, this pace becomes alienating, even boring. Finally, layering shot after shot after shot with no sense of hierarchy reduces the concept of cinematography to nothing but coverage. The shot becomes just data. The cinematographer is reduced to capturing data.

Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games trilogy is about a dystopian post-North America where tweens and teens are forced to kill each other on a nationally broadcast reality TV show. Our heroine is Katniss Everdeen – 16, and a loner who first experiences a boy’s romantic overtures as treachery, then as spiritual debt. With his every kindness, her indebtedness grows like a bad mortgage of the heart. Collins’ narratives are as non-erotic as Stephenie Meyer’s literary chastity belts, but you too might not be in the mood if, like Katniss, you were either starving, in pain or murdering children to survive. And while fans speculate endlessly over which boy Katniss would have chosen, I believe that, had she a choice, she would gladly have turned down both boys for one night of peace with her sister Prim and her mom. Readers of the trilogy know the truth of this.

Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games trilogy is about a dystopian post-North America where tweens and teens are forced to kill each other on a nationally broadcast reality TV show. Our heroine is Katniss Everdeen – 16, and a loner who first experiences a boy’s romantic overtures as treachery, then as spiritual debt. With his every kindness, her indebtedness grows like a bad mortgage of the heart. Collins’ narratives are as non-erotic as Stephenie Meyer’s literary chastity belts, but you too might not be in the mood if, like Katniss, you were either starving, in pain or murdering children to survive. And while fans speculate endlessly over which boy Katniss would have chosen, I believe that, had she a choice, she would gladly have turned down both boys for one night of peace with her sister Prim and her mom. Readers of the trilogy know the truth of this. Salander’s bad decision visibly diminishes her. Away goes the off-putting mohawk, bulky jacket, fetish gear and the essential protective hardness. She wears foundation, combs her hair and becomes “pretty.” She even buys Craig’s character an expensive leather jacket.

Salander’s bad decision visibly diminishes her. Away goes the off-putting mohawk, bulky jacket, fetish gear and the essential protective hardness. She wears foundation, combs her hair and becomes “pretty.” She even buys Craig’s character an expensive leather jacket. If so, check out The Thing, which took Salander-style self-determination as far as Hollywood could stand. Our heroine is a paleontologist named Kate Lloyd (Winstead); the blunt name matches her no-nonsense character. She ends up with a group of Norwegian scientists in the Antarctic fighting a shape-shifting alien menace. Dressed in the same gender blurring winter wear as her coworkers and with not a stitch of makeup, Kate is not attracting or attracted. Undistracted, she is relentless.

If so, check out The Thing, which took Salander-style self-determination as far as Hollywood could stand. Our heroine is a paleontologist named Kate Lloyd (Winstead); the blunt name matches her no-nonsense character. She ends up with a group of Norwegian scientists in the Antarctic fighting a shape-shifting alien menace. Dressed in the same gender blurring winter wear as her coworkers and with not a stitch of makeup, Kate is not attracting or attracted. Undistracted, she is relentless. Jump-cut from rom-coms to another form of action entirely, the Underworld films – those interchangeable video game-style werewolves-and-vampires shoot-outs featuring Kate Beckinsale in a catsuit. (Another is coming out next month.) I’d always assumed the films were about dudes ogling Beckinsale’s aerodynamic, leather-clad bod wreaking gory havoc. Wrong.

Jump-cut from rom-coms to another form of action entirely, the Underworld films – those interchangeable video game-style werewolves-and-vampires shoot-outs featuring Kate Beckinsale in a catsuit. (Another is coming out next month.) I’d always assumed the films were about dudes ogling Beckinsale’s aerodynamic, leather-clad bod wreaking gory havoc. Wrong.

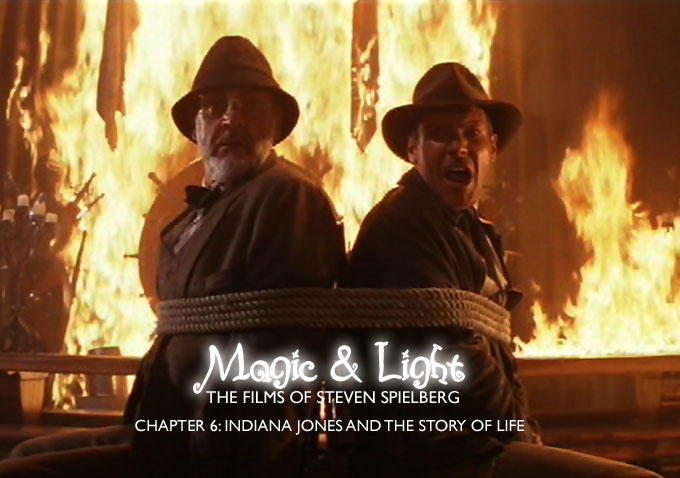

In later films we will learn that Indy has taken on the vocation of his father as a way to impress, and then one-up, the old man, a stern and distant academic. In Raiders, Indy is presented as almost a runaway kid, a grown-up Bowery Boy who doesn’t give much thought to others. He possesses the shallowness of youth, complete with the clichéd woman in every port. He’s a heartbreaker, this one.

In later films we will learn that Indy has taken on the vocation of his father as a way to impress, and then one-up, the old man, a stern and distant academic. In Raiders, Indy is presented as almost a runaway kid, a grown-up Bowery Boy who doesn’t give much thought to others. He possesses the shallowness of youth, complete with the clichéd woman in every port. He’s a heartbreaker, this one. When Indy, Willie, and Short Round come across a village, they discover all of the children have been kidnapped and forced into slave labor in the mines of the Thugee cult. In effect, the bad guys in this film have made the entire village childless, and turned all the kids into orphans by kidnapping them.

When Indy, Willie, and Short Round come across a village, they discover all of the children have been kidnapped and forced into slave labor in the mines of the Thugee cult. In effect, the bad guys in this film have made the entire village childless, and turned all the kids into orphans by kidnapping them. While the elder Jones didn’t literally abandon his family to pursue his obsession, we have no doubt that a lot of the time when Indy was growing up, the old man was mentally or emotionally checked-out. You can see it in the way they communicate – or more accurately, don’t communicate.

While the elder Jones didn’t literally abandon his family to pursue his obsession, we have no doubt that a lot of the time when Indy was growing up, the old man was mentally or emotionally checked-out. You can see it in the way they communicate – or more accurately, don’t communicate. Released almost twenty years after the last Indiana Jones film, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull feels like a coda. Indy seems to be re-thinking his decisions, and having pangs of regret. Although the sixty-something Indy is still a snarling, leathery ass-kicker, and in what might be his surliest mood since the middle section of Temple of Doom, the movie’s overall tone is rueful and melancholy.

Released almost twenty years after the last Indiana Jones film, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull feels like a coda. Indy seems to be re-thinking his decisions, and having pangs of regret. Although the sixty-something Indy is still a snarling, leathery ass-kicker, and in what might be his surliest mood since the middle section of Temple of Doom, the movie’s overall tone is rueful and melancholy.

As in Romero’s The Crazies, Right at Your Door evokes a world where authority figures are visibly shown to be unreliable. This is extraordinary in Right at Your Door because authority figures are only physically represented by armed grunts clad in gas masks and biohazard jumpsuits. These monsters are just following orders when they don’t answer Brad’s questions. For example, one can't help but notice the way one soldier hesitates and even trembles while puffing out his chest and defensively telling Brad, “We’re not trying to cause more panic than there already is.” Compare that with the way the similarly dressed soldiers in The Crazies are defined by their actions. They don’t use verbal prompts that might even tentatively reveal their humanity. By contrast, Gorak's army men reveal their humanity while they’re doing the most cruelly impersonal things.

As in Romero’s The Crazies, Right at Your Door evokes a world where authority figures are visibly shown to be unreliable. This is extraordinary in Right at Your Door because authority figures are only physically represented by armed grunts clad in gas masks and biohazard jumpsuits. These monsters are just following orders when they don’t answer Brad’s questions. For example, one can't help but notice the way one soldier hesitates and even trembles while puffing out his chest and defensively telling Brad, “We’re not trying to cause more panic than there already is.” Compare that with the way the similarly dressed soldiers in The Crazies are defined by their actions. They don’t use verbal prompts that might even tentatively reveal their humanity. By contrast, Gorak's army men reveal their humanity while they’re doing the most cruelly impersonal things.

Carrie’s a character whose entire life, as the brilliant credits sequence reminds us every week, is literally defined by terrorism, fear and trying to control that fear by building a life, a personage as a person in strict control, serving her country, her profession and the one real man in her life, her mentor and father figure Saul Berenson (the mighty Mandy Patinkin).

Carrie’s a character whose entire life, as the brilliant credits sequence reminds us every week, is literally defined by terrorism, fear and trying to control that fear by building a life, a personage as a person in strict control, serving her country, her profession and the one real man in her life, her mentor and father figure Saul Berenson (the mighty Mandy Patinkin). Right, bipolar disorder. I didn’t mention that, to add some tension spice to Carrie’s character, Homeland makes Carrie suffer really badly from bipolar disorder. Like, it’s so bad that she has to take her meds every day or else she’ll go into a manic tailspin and lose her mind. The poor thing, she can’t even go to a regular doctor for those meds because the C.I.A. would kick her out as a security risk. So, she visits her psychiatrist sister on the down-low for her weekly supply, which translates into even more suspense, and some shame and anxiety to boot; this bipolar thing is paying off big-time and all they had to do was say she has it. Poor Carrie. This is going to be one rough season.

Right, bipolar disorder. I didn’t mention that, to add some tension spice to Carrie’s character, Homeland makes Carrie suffer really badly from bipolar disorder. Like, it’s so bad that she has to take her meds every day or else she’ll go into a manic tailspin and lose her mind. The poor thing, she can’t even go to a regular doctor for those meds because the C.I.A. would kick her out as a security risk. So, she visits her psychiatrist sister on the down-low for her weekly supply, which translates into even more suspense, and some shame and anxiety to boot; this bipolar thing is paying off big-time and all they had to do was say she has it. Poor Carrie. This is going to be one rough season. Don't get me wrong: I don’t suggest Homeland hang itself on the horns of scientific accuracy (or a WebMD search). I just ask that it create a ‘verse where there are laws for Carrie’s condition, and then stick to those laws, like the way Vulcans can or can’t intermarry and the like. (On the other hand, absurdity met ugliness when the showrunners had Carrie, in deep depression, diagnosing herself – with her sister mutely complicit – for electroconvulsive therapy, a.k.a. shock treatment, a controversial, risky, cognition- and memory-impairing but highly photogenic treatment calling for Danes to be strapped and gagged, electrodes glued to her scalp. Then they cranked the juice as her body spasmed grotesquely. If you’re suffering from depression, there are a million other ways to get help – this is just an ignorant TV show by the guys who made the torture-happy 24.)

Don't get me wrong: I don’t suggest Homeland hang itself on the horns of scientific accuracy (or a WebMD search). I just ask that it create a ‘verse where there are laws for Carrie’s condition, and then stick to those laws, like the way Vulcans can or can’t intermarry and the like. (On the other hand, absurdity met ugliness when the showrunners had Carrie, in deep depression, diagnosing herself – with her sister mutely complicit – for electroconvulsive therapy, a.k.a. shock treatment, a controversial, risky, cognition- and memory-impairing but highly photogenic treatment calling for Danes to be strapped and gagged, electrodes glued to her scalp. Then they cranked the juice as her body spasmed grotesquely. If you’re suffering from depression, there are a million other ways to get help – this is just an ignorant TV show by the guys who made the torture-happy 24.) Meanwhile, in Brody’s frequent shirtless scenes we see his scars and their implied memories of unimaginable months of pain and horror, which now have no apparent effect. (Even his attempted terrorist act is based not on torture, but on love of a child.) This is Spielbergism; take a sad song and make it ludicrously better, one-upping it by saying the sad song doesn’t exist even as you’re looking at it.

Meanwhile, in Brody’s frequent shirtless scenes we see his scars and their implied memories of unimaginable months of pain and horror, which now have no apparent effect. (Even his attempted terrorist act is based not on torture, but on love of a child.) This is Spielbergism; take a sad song and make it ludicrously better, one-upping it by saying the sad song doesn’t exist even as you’re looking at it.