[EDITOR'S NOTE: Fearless Sarah D. Bunting of Tomatonation.com is making it her mission to watch every single film nominated for an Oscar before the Academy Awards Ceremony on February 26, 2012. She is calling this journey her Oscars Death Race. For more on how the Oscars Death Race began, click here. And you can follow Sarah through this quixotic journey here.]

In the press notes I received at the screening of Footnote, writer/director Joseph Cedar comments that his film "qualifies as a tragedy, as most father-son stories do." It's a big statement; what's interesting about Footnote — if not entirely successful — is how Cedar presents that tragedy.

Describing the plot without spoiling its central elements is difficult, but basically, Eliezer Shkolnik (Shlomo Bar Aba) is a professor at the Hebrew University, a Talmudic scholar whose micro-focused research has gone largely unappreciated thanks to bad timing, academic backbiting, and Eliezer's immutably sour personality. His son, Uriel (Lior Ashkenazi), is a professor in the same department; his focus is broader, more civilian-friendly. Naturally, there is competition between father and son, although it isn't spoken of between them…until the precipitating event, it isn't spoken of at all, and even that event and its ensuing complications across the family doesn't force that conversation out in the open. It takes place through articles, footnotes, and the ways father and son read and write them.

Describing the plot without spoiling its central elements is difficult, but basically, Eliezer Shkolnik (Shlomo Bar Aba) is a professor at the Hebrew University, a Talmudic scholar whose micro-focused research has gone largely unappreciated thanks to bad timing, academic backbiting, and Eliezer's immutably sour personality. His son, Uriel (Lior Ashkenazi), is a professor in the same department; his focus is broader, more civilian-friendly. Naturally, there is competition between father and son, although it isn't spoken of between them…until the precipitating event, it isn't spoken of at all, and even that event and its ensuing complications across the family doesn't force that conversation out in the open. It takes place through articles, footnotes, and the ways father and son read and write them.

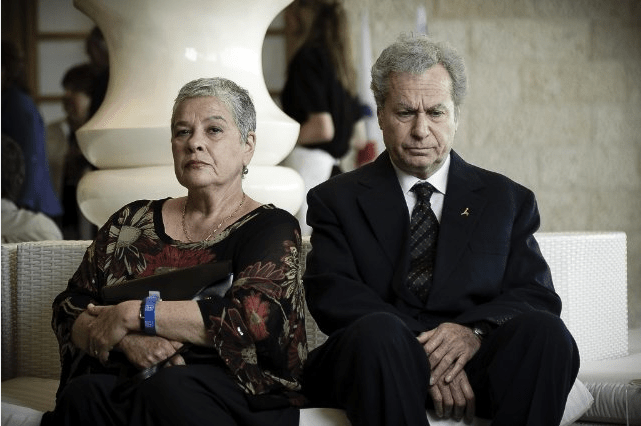

Cedar often plays this silent tension for laughs, using list chyrons and cueing melodramatic chords on the score. The sound design amps up some effects and drops out others to parallel the selective understandings of the characters; when Uriel gives a speech accepting an award, the camera stays steady on Eliezer's unkempt eyebrows and bilious stare into the middle distance while the sound of his irritated breathing slowly crescendos. Later, as Eliezer and his strangely impassive wife, Uriel's mother Yehudit (Alisa Rosen), proceed into an auditorium, footsteps and airplane-y white noise dominate.

Cedar's decision not to include a confrontation between Eliezer and Uriel — or a discussion between Eliezer and Yehudit, or much reaction from Yehudit at all — is both maddening and refreshing. The "closure" we may have unconsciously come to expect in chapters of filial pain and disappointment is something most of us have to live without in real life; more to the point, it's true to these characters, emotionally bleak but truthful.

The execution doesn't always work. One scene featuring the university's most decorated minds crammed into a meeting "room" the size of a toaster oven is a deft visual gag, but the dialogue should move faster and include more over-talking (tip of the hat to Ashkenazi for the elegance of his straight-to-camera exposition-dumping here, though). And Yehudit's blankness might be too tough to read. Not knowing how she feels is one thing, but I'm not sure I know that she feels. Not that that couldn't work too, in context, but I needed a little more from that character.

But it does a handful of nifty things — the set design of an academic's teetering-book-pile-hole of an office is dead on, for one — and I feel confident in declaring "cookie recipes in the Babylonian Diaspora" the Oscars Death Race Subtitle of the Week.

Sarah D. Bunting co-founded Television Without Pity.com, and has written for Seventeen, New York Magazine, MSNBC.com, Salon, Yahoo!, and others. She's the chief cook and bottle-washer at TomatoNation.com. For more on how the Oscars Death Race began, click here.

At some point, a show stops being a show and becomes a utility: gas, electricity, water, The Simpsons. That’s not my line; it’s cribbed from a quote about 60 Minutes by its creator, the late Don Hewitt. But it seems appropriate to recycle a point about one long-running program in an article about another when it’s as self-consciously self-cannibalizing as The Simpsons. Matt Groening’s indestructible cartoon sitcom has run 23 seasons and will air its 500th episode on February 19. It hasn’t been a major cultural force in a decade or more, unless you count 2007’s splendid The Simpsons Movie, but it’s still the lingua franca of pop-culture junkies, quoted in as many contexts as the Holy Bible and Star Wars, neither of which includes lines as funny as “Me fail English? That’s unpossible!” I haven’t seen the 500th installment yet because it wasn’t done when I wrote this piece, and that’s probably for the best; pin a thesis to any single chapter and the kaleidoscopic parade of The Simpsons will stomp it flat. Early in the show’s run we rated episodes. Now we rate seasons. In seven years, we’ll be rating decades.

At some point, a show stops being a show and becomes a utility: gas, electricity, water, The Simpsons. That’s not my line; it’s cribbed from a quote about 60 Minutes by its creator, the late Don Hewitt. But it seems appropriate to recycle a point about one long-running program in an article about another when it’s as self-consciously self-cannibalizing as The Simpsons. Matt Groening’s indestructible cartoon sitcom has run 23 seasons and will air its 500th episode on February 19. It hasn’t been a major cultural force in a decade or more, unless you count 2007’s splendid The Simpsons Movie, but it’s still the lingua franca of pop-culture junkies, quoted in as many contexts as the Holy Bible and Star Wars, neither of which includes lines as funny as “Me fail English? That’s unpossible!” I haven’t seen the 500th installment yet because it wasn’t done when I wrote this piece, and that’s probably for the best; pin a thesis to any single chapter and the kaleidoscopic parade of The Simpsons will stomp it flat. Early in the show’s run we rated episodes. Now we rate seasons. In seven years, we’ll be rating decades.

Brad Pitt’s performance is an almost old-fashioned, movie star one. In another universe, one could imagine Jimmy Stewart or Cary Grant taking the part. He brings to the role an assured quality on overzealous, yet understated, lust for ultimate success that was forged in the fires of years and years of failure. He's charming and cheeky and funny, and very good looking (despite the hideous early naughties’ haircut and lumbering fashion sense). Pitt brings a subtle comedic take to what could have been a rather boring central role; his various dealings with other managers, his scouts and players, betray genius-level timing and mimicry.

Brad Pitt’s performance is an almost old-fashioned, movie star one. In another universe, one could imagine Jimmy Stewart or Cary Grant taking the part. He brings to the role an assured quality on overzealous, yet understated, lust for ultimate success that was forged in the fires of years and years of failure. He's charming and cheeky and funny, and very good looking (despite the hideous early naughties’ haircut and lumbering fashion sense). Pitt brings a subtle comedic take to what could have been a rather boring central role; his various dealings with other managers, his scouts and players, betray genius-level timing and mimicry.

Oskar is a wise child. Why do I think to describe him that way? Well, to start with,

Oskar is a wise child. Why do I think to describe him that way? Well, to start with,  During Oskar’s journey, a great many people (most of them with the surname “Black”) come into his orbit, including a hulking, silent Swede (Max von Sydow) who might be his grandfather and is certainly a kindred spirit. Oskar also sees his glorious city from every angle. As filmed by director Stephen Daldry and cameraman Chris Menges, Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close is one of the great New York movies. It resembles The World of Henry Orient, with precocious young New Yorkers darting around the city unencumbered by adult supervision.

During Oskar’s journey, a great many people (most of them with the surname “Black”) come into his orbit, including a hulking, silent Swede (Max von Sydow) who might be his grandfather and is certainly a kindred spirit. Oskar also sees his glorious city from every angle. As filmed by director Stephen Daldry and cameraman Chris Menges, Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close is one of the great New York movies. It resembles The World of Henry Orient, with precocious young New Yorkers darting around the city unencumbered by adult supervision. It is a great portrait of motherhood. The movie may seem all gilded surfaces, but the truths it contains are straightforward, and so many of them spring from Bullock’s quiet, easy performance. You want to cry softly when she whispers that what she misses most about her husband is his voice. It is a simple thing to miss, but any bereaved person can relate. I do not think Sandra Bullock has given a more natural or unaffected performance since Peter Bogdanovich’s The Thing Called Love.

It is a great portrait of motherhood. The movie may seem all gilded surfaces, but the truths it contains are straightforward, and so many of them spring from Bullock’s quiet, easy performance. You want to cry softly when she whispers that what she misses most about her husband is his voice. It is a simple thing to miss, but any bereaved person can relate. I do not think Sandra Bullock has given a more natural or unaffected performance since Peter Bogdanovich’s The Thing Called Love.

The power of the performance is in Davis’ eyes. They take in everything – tossed-off racist remarks, a child’s need to be comforted. And her voice, which never rises above a formal submissiveness, quivers with a boiling anger that stands for generations of women whose hard work goes unnoticed. It’s a voice that needs to be heard.

The power of the performance is in Davis’ eyes. They take in everything – tossed-off racist remarks, a child’s need to be comforted. And her voice, which never rises above a formal submissiveness, quivers with a boiling anger that stands for generations of women whose hard work goes unnoticed. It’s a voice that needs to be heard.

0 COMMENTS