[EDITOR'S NOTE: The end is rapidly approaching and Sarah D. Bunting of Tomatonation.com is down to the category for Documentary Shorts. Here, she picks the Oscar in the Best Picture category. She has very nearly watched every single film nominated for an Oscar this year. She is calling this journey her Oscars Death Race. For more on how the Oscars Death Race began, click here. And you can follow Sarah through this quixotic journey here. It's a tough job. But, someone has to do it.]

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The end is rapidly approaching and Sarah D. Bunting of Tomatonation.com is down to the category for Documentary Shorts. Here, she picks the Oscar in the Best Picture category. She has very nearly watched every single film nominated for an Oscar this year. She is calling this journey her Oscars Death Race. For more on how the Oscars Death Race began, click here. And you can follow Sarah through this quixotic journey here. It's a tough job. But, someone has to do it.]

NYMag's David Edelstein posits that The Artist is a lock for the gold on Sunday, and I don't disagree, with the conclusion or the reasoning. It's a weird year for the Best Pic slate, with a lot of seriously-flawed-at-best material; it might come down to the least of nine evils.

The evil-lope, please…

The nominees

The nominees

The Artist. As Edelstein notes, it's charming — charming enough. Some found it too self-consciously charming, but a lot of people saw it…and a lot of people felt good and smart about themselves for seeing it. The presumptive winner.

The Descendants. Went off the boil a few weeks ago, which is fine by me, as I despised it across the board. Not a terrible pick for your pool, but unlikely.

Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close. Man, people are REALLY afraid of Scott Rudin, eh? …I would drop a "just kidding" in here if I could find another reason for the nomination, but I can't. Widely, and correctly, reviled by critics; no chance.

The Help. Wonderful performances almost get the white-guilty writing out of its own way, but not quite. A long shot.

Hugo. I admired it a great deal, and while it's not something I will rush to buy on DVD, of the group this year, I think it's the most…complete, I guess. It's a story for all ages, the acting is good, the writing is a little strange but mostly good, the director pushed himself and the format, and it's pretty. It could win, but I would bet it for Best Directing, not here.

Midnight in Paris. A past-masters nomination, I suspect, for a likeable but redundant Woody Allen movie. No chance.

Moneyball. A very good movie that exceeded my expectations by a wide margin; it's built well. For whatever reason — too niche? — it's not in the discussion, which is unfortunate, but the nomination is the award.

The Tree of Life. A part of me wants it to win, because it didn't work for me, but I still think it's important, from an event standpoint and from a "half the fun of watching movies is talking about them afterwards" standpoint. Plus, watching people lose their fookin' minds on Twitter about it at 11:55 PM? Awesome. "Divisive" won't get it done, though, and I don't think it has enough friends in the room.

War Horse. Gorgeous but undisciplined outing from Spielberg that might feel too "children's" to pull many votes. Doubtful.

War Horse. Gorgeous but undisciplined outing from Spielberg that might feel too "children's" to pull many votes. Doubtful.

Who shouldn't be here: I'll just say it: most of them. EL&IC is the most egregious, but this is another category where it's not who's here. It's who's not.

Who should be here, but isn't: I was disappointed in Tinker Tailor, but it's ambitious, at least, and it's better than several of the nominees. So is Win Win. So is Meek's Cutoff. So is the entire Best Foreign Language category. Seriously, where is A Separation — it pulled a screenplay nom, it got decent distribution compared to its category-mates, and it has a basic understanding of how human beings speak to one another, which is not something you can say for about half the BP slate. Where's Rango? Where's Bridesmaids, for that matter?

I get a whiff of "let's not bother nominating things the Academy voters won't make an effort to see" from the nominees this year. …Well, every year, but it's not usually the bulk of the list. I have absolutely no problem with nominating popular entertainments that did big box office, but if films got passed over as too challenging to the voters, that's horseshit. The rest of us have to pretend to take these awards seriously for 17 months out of the year, so the voters can take them seriously too, or they can step aside. Fall asleep reading subtitles? You're excused. Can't follow complicated plots? You're excused. "But how do I get the 3D glasses to go over my bifoca–" You're excused. You don't have to drive to Montreal and back in one day to see Monsieur Lazhar like one crazy lady I might mention, but if "best" means "least likely to inconvenience members of the industry whose kings we are crowning in front of the entire world on TV"? Not good enough.

ATTICA! ATTICA! ATTICA! …Hee. Sorry about that. I'm a little tired over here. To the prediction-mobile, let's go!

Who should win: Hugo or Moneyball

Who will win: The Artist

Who needs a binky and a nap: This brother

Sarah D. Bunting co-founded Television Without Pity.com, and has written for Seventeen, New York Magazine, MSNBC.com, Salon, Yahoo!, and others. She's the chief cook and bottle-washer at TomatoNation.com. For more on how the Oscars Death Race began, click here.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The end is rapidly approaching and Sarah D. Bunting of

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The end is rapidly approaching and Sarah D. Bunting of  Best Directing is a more difficult call, at least for me, because the tendency is to both praise and blame the director for anything and everything, even if we have no real information on what s/he could control inside the production. On the plus side, we really only have to consider three of the five directors on the list. Payne will win elsewhere for The Descendants, but I didn't see him doing anything above and beyond with the structure or the look of the story. Woody Allen could direct this picture in his sleep — and may have, with The Purple Rose of Manhattan tucked under his pillow. It's The Artist, Hugo, and The Tree of Life.

Best Directing is a more difficult call, at least for me, because the tendency is to both praise and blame the director for anything and everything, even if we have no real information on what s/he could control inside the production. On the plus side, we really only have to consider three of the five directors on the list. Payne will win elsewhere for The Descendants, but I didn't see him doing anything above and beyond with the structure or the look of the story. Woody Allen could direct this picture in his sleep — and may have, with The Purple Rose of Manhattan tucked under his pillow. It's The Artist, Hugo, and The Tree of Life.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The Oscars Death Race is almost over and Sarah D. Bunting of

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The Oscars Death Race is almost over and Sarah D. Bunting of  Moneyball is, for my money, the best writing on offer here. It's Sorkin-y, but in the good ways; it lets the actors work, but isn't too indulgent of them; and it brought what I assumed was an unfilmable book to the screen. If I had a vote, I'd spend it on this.

Moneyball is, for my money, the best writing on offer here. It's Sorkin-y, but in the good ways; it lets the actors work, but isn't too indulgent of them; and it brought what I assumed was an unfilmable book to the screen. If I had a vote, I'd spend it on this. Bridesmaids. I liked the movie, but I had some issues with the length, and with the frat pandering. The writing did shine in the less showy scenes, like the scene at the beginning with the two friends at brunch, but I don't think it should win, and it won't.

Bridesmaids. I liked the movie, but I had some issues with the length, and with the frat pandering. The writing did shine in the less showy scenes, like the scene at the beginning with the two friends at brunch, but I don't think it should win, and it won't.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The end is rapidly approaching and Sarah D. Bunting of

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The end is rapidly approaching and Sarah D. Bunting of

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The end is rapidly approaching and Sarah D. Bunting of

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The end is rapidly approaching and Sarah D. Bunting of

Makeup effects were always a key component of the movies. Greasepaint, wigs, putty, latex appliances and other items in the makeup master's toolkit helped make the improbable, and the impossible, seem vividly real. Boris Karloff could make us believe that he was a tormented, tragic creature built from pieces of dead men in Universal's Frankenstein films – with makeup by the great Jack Pierce. Pierce's work on The Wolfman made an ordinary man become a werewolf when the wolfbane bloomed and the moon was full and bright. A 25-year-old Orson Welles played the title character of Citizen Kane at a dazzling array of ages, thanks to inventive, at times highly theatrical effects by Maurice Seiderman.

Makeup effects were always a key component of the movies. Greasepaint, wigs, putty, latex appliances and other items in the makeup master's toolkit helped make the improbable, and the impossible, seem vividly real. Boris Karloff could make us believe that he was a tormented, tragic creature built from pieces of dead men in Universal's Frankenstein films – with makeup by the great Jack Pierce. Pierce's work on The Wolfman made an ordinary man become a werewolf when the wolfbane bloomed and the moon was full and bright. A 25-year-old Orson Welles played the title character of Citizen Kane at a dazzling array of ages, thanks to inventive, at times highly theatrical effects by Maurice Seiderman. The 1960s through the 1980s were the high point of traditional, analog filmmaking techniques. Some of the most memorable films from this era showed transformation, decay and violence with unprecedented realism. Some of the most striking makeup effects of this period were the work of one man, Dick Smith, who finally received a special Oscar from the Academy in 2012 after decades of groundbreaking work. Nobody spilled blood with more panache.

The 1960s through the 1980s were the high point of traditional, analog filmmaking techniques. Some of the most memorable films from this era showed transformation, decay and violence with unprecedented realism. Some of the most striking makeup effects of this period were the work of one man, Dick Smith, who finally received a special Oscar from the Academy in 2012 after decades of groundbreaking work. Nobody spilled blood with more panache. The late 1970s saw makeup effects moving away from realistic applications and moving toward the extremes of fantasy. Christopher Tucker's remarkable makeup for David Lynch's 1980 drama The Elephant Man may have pushed the Academy to start handing out a Best Makeup award the following year. After eight decades' worth of movie makeup effects, and 20 years of rapid technical innovations, to continue ignoring the makeup artist's craft would have seemed perverse. And speaking of perverse….

The late 1970s saw makeup effects moving away from realistic applications and moving toward the extremes of fantasy. Christopher Tucker's remarkable makeup for David Lynch's 1980 drama The Elephant Man may have pushed the Academy to start handing out a Best Makeup award the following year. After eight decades' worth of movie makeup effects, and 20 years of rapid technical innovations, to continue ignoring the makeup artist's craft would have seemed perverse. And speaking of perverse…. The Oscar for American Werewolf signaled that the 1980s – the decade of high-concept blockbusters – would be the golden age of analog makeup effects. When you look back over genre movies from the period – small and big, sensitive and crass, clichéd and innovative – the special effects often hold up surprisingly well. In some cases they're the main reason that people still talk about the movies. Modern makeup effects are slicker and more consistent from scene to scene and shot to shot for reasons that we'll get to in a minute. But, given the mechanical limitations of the pre-digital era, their achievements are still impressive. Even when the storytelling falters, or when the film itself seems less an artistic statement than the end result of a studio deal memo, you can still see the behind-the-scenes craftspeople working at the peak of their powers, always striving to innovate and impress.

The Oscar for American Werewolf signaled that the 1980s – the decade of high-concept blockbusters – would be the golden age of analog makeup effects. When you look back over genre movies from the period – small and big, sensitive and crass, clichéd and innovative – the special effects often hold up surprisingly well. In some cases they're the main reason that people still talk about the movies. Modern makeup effects are slicker and more consistent from scene to scene and shot to shot for reasons that we'll get to in a minute. But, given the mechanical limitations of the pre-digital era, their achievements are still impressive. Even when the storytelling falters, or when the film itself seems less an artistic statement than the end result of a studio deal memo, you can still see the behind-the-scenes craftspeople working at the peak of their powers, always striving to innovate and impress.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The end is rapidly approaching and Sarah D. Bunting of

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The end is rapidly approaching and Sarah D. Bunting of  This felt forced, though — out of sync, like a hitter in a slump who swings too hard or too late. The whispered voice-overs do reflect the things some of us say to God, but "realistic" doesn't necessarily mean "interesting," and the murmurs become redundant after a while, then almost parodic. Ditto the gazillion scenes of the kids playing, and/or their mother (Jessica Chastain) providing a safe Rockwellian haven from the cardboard abusiveness of O'Brien Sr. (Brad Pitt); it's not the repetition itself, really, but the pacing, which occasionally felt like a screensaver designed by a joint coalition of Scientific American and Betty Friedan.

This felt forced, though — out of sync, like a hitter in a slump who swings too hard or too late. The whispered voice-overs do reflect the things some of us say to God, but "realistic" doesn't necessarily mean "interesting," and the murmurs become redundant after a while, then almost parodic. Ditto the gazillion scenes of the kids playing, and/or their mother (Jessica Chastain) providing a safe Rockwellian haven from the cardboard abusiveness of O'Brien Sr. (Brad Pitt); it's not the repetition itself, really, but the pacing, which occasionally felt like a screensaver designed by a joint coalition of Scientific American and Betty Friedan.

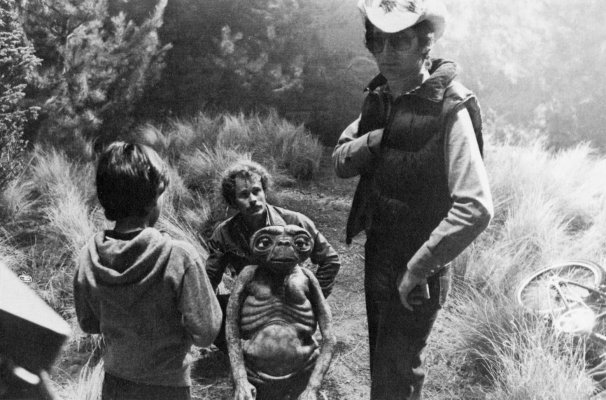

If you doubt it, go back and watch Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back, the Star Wars film that introduced Frank Oz’s first great non-Muppet character, the 800-year old, swamp-dwelling Jedi master Yoda.

If you doubt it, go back and watch Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back, the Star Wars film that introduced Frank Oz’s first great non-Muppet character, the 800-year old, swamp-dwelling Jedi master Yoda. You never see Frank Oz when you’re watching Yoda. When he performs the character, he’s hidden behind props or underneath a platform. But this is nevertheless a performance, one that’s as imaginative, serious and engaging as any that are given by the movie’s human characters. Maybe more so. In the training scene with Luke, Yoda is mainly played by a dummy, affixed to the shoulders of actor Mark Hamill and the stuntman who plays Luke during his more acrobatic moments. The sequence relies entirely on our suspension of disbelief, carried over from earlier scenes that were more obviously dominated by Frank Oz the puppeteer.

You never see Frank Oz when you’re watching Yoda. When he performs the character, he’s hidden behind props or underneath a platform. But this is nevertheless a performance, one that’s as imaginative, serious and engaging as any that are given by the movie’s human characters. Maybe more so. In the training scene with Luke, Yoda is mainly played by a dummy, affixed to the shoulders of actor Mark Hamill and the stuntman who plays Luke during his more acrobatic moments. The sequence relies entirely on our suspension of disbelief, carried over from earlier scenes that were more obviously dominated by Frank Oz the puppeteer.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: Fearless Sarah D. Bunting of

[EDITOR'S NOTE: Fearless Sarah D. Bunting of