"The thing is, directors and studios don't really like each other." Graphic designer Erik Buckham ought to know. He has a ringside seat. He designs movie posters. The nature of the business means that he deals with both studio marketing departments and control freak directors, but not always in equal measure. This comment explains a lot about why American movies look the way they do and a lot about why Buckham prefers to work on small films rather than big.

If you don't know Buckham's name, you probably know his work. His most famous poster is probably the "You don't get to 500 million friends…" poster for The Social Network. True/False asked him to design their poster and graphics this year and brought him to the festival to speak about what he does. He brought a slideshow of his past work, including multiple variations that never made the cut, as well as pieces that show the evolution of the concepts that make up his final work.

The process of making the True/False graphics was the centerpiece of the talk, and it showcased the evolution of image from concept to final product. The theme of this year's True/False festival, both in its visual presentation and in the various artworks scattered around the venues, is film as an "Influence Machine," and the final result progressed from fairly abstract, illustration-y images to a steampunk Van de Graaf generator, cobbled together in the poster art as a photo collage, and in real life as a huge sculpture in the lobby of the Missouri Theater. It also features in the arresting bumper reels that play at the beginning of each film.

Friday is when True/False transforms into a kind of arts carnival. Most of the shows have opening acts of busking musicians who pass a hat around the audience. I wish there were a greater diversity of musicians and musical styles beyond the kind of 1990s-ish indie folk rock that dominates the fest, but not enough to grouse overly much. The Friday parade up at the Boone County courthouse seems like a combination of open-air rave and homecoming celebration, complete with marching band. And, as I mentioned, there's art scattered across the various venues. All of this gives True/False its flavor.

The opening scenes of Building Babel (directed by David Osit) are a study in contrasts. First, we see the huge twin spotlights that mark the site of the World Trade Center. On the soundtrack are the phone messages directed at Sharif el-Gamal, the man behind the Park 51 Islamic Community Center–popularly misidentified as the "Ground Zero Mosque". The messages are a mixture of invective and nativist bigotry. To the callers, el-Gamal is an Islamic invader. The scene then switches to el-Gamal's home life as he gets his daughters ready for school. The man we meet in this scene is an American, born and bred in Brooklyn to a Catholic mother and a Muslim father. In his demeanor and his speech, he's a New Yorker, not different in any significant way from a devout New York Jew or New York Catholic. Therein lies the thesis of the movie. It wants to paint a broader picture of what it means to be an American, a picture that includes people like el-Gamal and his family. It wants to be a rebuke to nativism.

The movie's ostensible narrative finds el-Gamal and his team fending off an attempt to get the old Burlington Coat Factory where he's set up shop as a landmark building. There's nothing particularly notable about the building except its proximity to the World Trade Center. A piece of airplane wreckage fell on it on 9/11. Making it a landmark would prevent el-Gamal from remodeling the property. At the time, the building was in a state of dereliction, so it would unintentionally freeze it as a derelict, which seems antithetical to the idea of a landmark. Al-Gamal's team (rightly) argue that being in the path of a disaster isn't enough to make it a landmark. Does the guard rail that James Dean drove through on his way to his death qualify as a landmark? Most sensible people would say no, and the landmark commission turns out to be unanimously sensible.

In some respects, the community center and the uproar around it is beside the point. The film gives it lip service–it can't avoid it–but it expends more energy painting Sharif and his family as an all-American family, just like any other American family, and it's largely successful at this. It doesn't deal with a fundamental problem in its thesis, though: why does it matter? If he is otherwise law-abiding, if he is otherwise a good citizen, what does it matter if he is totally assimilated or not? This is always the problems of a minority living within a majority, and the absence of a discussion of this is an elephant standing in the room. The movie works better as a character study of el-Gamal himself. It shows him warts and all. He's obviously an affable guy. He loves his kids and his wife, Rebecca (who is almost an equal partner in the film's attentions). He's a businessman who has bitten off a project for which he's totally unprepared. Still, he's perpetually optimistic, and that makes him archetypically American.

Building Babel was preceded by "Paraiso" (directed by Nadav Kurtz), a short film about skyscraper window washers in Chicago. I liked it better than the feature. Apart from the vertiginous locations over the sides of some very tall buildings–Mission: Impossible has nothing on this–it also touches on a bittersweet sense of mortality as its workers all contemplate their own deaths should they fall from their workplace. A beautiful film.

True/False isn't strictly a documentary festival. Its mission from the outset has been to showcase films in the fuzzy shadowland between truth and fiction, so it's not out of character at all for them to screen fiction. Last year, they showed Troll Hunter, based on its mockumentary styling. This year, they have V/H/S, a new wrinkle on the "found footage" subgenre. New wrinkles are sometimes wrapped around old forms, and in spite of its lo-res, found footage conceit, this is a familiar kind of film. This is our old friend, the anthology horror movie returned to life. V/H/S is a film that Milton Subotsky would have greenlit at Amicus in a heartbeat back in 1971. It's a close cousin to films like Tales from the Crypt, The House that Dripped Blood, and Torture Garden. There are five stories and a framing sequence. Like all anthologies, it's highly variable.

The premise finds a group of sociopathic friends hired to retrieve a mysterious VHS tape from a sinister house. Our "heroes" like to film their stunts, so they take their cameras with them. In the house, they find a dead body and a plethora of videotapes containing disturbing footage. The tapes they find provide the individual stories. In one, a couple of partying dudebros pick up the wrong woman in a bar, in another, a woman brings some of her friends into the woods to act as bait for a mad slasher. My favorite finds a couple on a second honeymoon terrorized by a mysterious woman who films them while they sleep. My least favorite finds another pack of partying dude bros lured to a haunted house. Mostly, they're all of a piece.

As far as horror movie tropes go, this doesn't reinvent the wheel. We get vampires and long-haired ghost girls and a haunted house. The slasher film segment provides a droll take on the penchant of mad slashers to move around the movie via off-screen teleportation. None of this is exactly new. What IS new is the form. Mostly filmed handheld and occasionally nausea inducing, this has a veneer of raw, undoctored footage (which, of course, it isn't–there are plenty of special effects). It's not unwatchable, but it takes some getting used to. I'm less sanguine about the depiction of gender in this film. Men in this movie are all douchebags. Women are generally there to be abused. The opening of the film has some disturbing rape imagery, while date rape figures into the first story and killer lesbians figure into another. I know that character development isn't necessarily the genre's strong point, especially in short form, but this film suffers from the lack more than most.

Watching V/H/S provided a nice callback to the Erik Buckham seminar earlier in the day because Buckham claimed the covers of old horror VHS tapes as one of his prime inspirations. He designed the art for The House of the Devil, too, and one of V/H/S's directors is Ti West. The experience of watching it is like sampling a bunch of old VHS horror movies after they've degraded a bit. Visually, the lo-fi grottiness of V/H/S is in the tradition of crappy 16mm blown up to 35 or the filmed through a glaze of dirt aesthetic of, say, Basket Case or I Spit on Your Grave. It's generally better than those movies, though it should be taken with a grain of salt.

Christiane Benedict is a writer and graphic artist who lives in Columbia, Missouri. She blogs at Krell Laboratories.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The True/False Film Festival, one of the leading showcases for nonfiction filmmaking in the US, unspools its ninth edition this weekend in Columbia, Missouri. We'll be featuring daily reports on the festival from film writer Christianne Benedict, a Columbia native who has attended and reported on the film festival since its beginning.

EDITOR'S NOTE: The True/False Film Festival, one of the leading showcases for nonfiction filmmaking in the US, unspools its ninth edition this weekend in Columbia, Missouri. We'll be featuring daily reports on the festival from film writer Christianne Benedict, a Columbia native who has attended and reported on the film festival since its beginning.

Still, it’s important to note that Gein isn’t really a serial killer. He murdered two people, which hardly establishes his slayings as a pattern. But he is important because he became a symbol of all the Freudian motivations that we project onto killers. We make these assumptions partly because of the phallic imagery implicit in Psycho’s shower scene or Leatherface’s chainsaw in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Massacre director Tobe Hooper would make a lot of hoopla over Leatherface’s fetish in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, which plays out like a fittingly schizophrenic and limp slasher made by a big Laura Mulvey fan).

Still, it’s important to note that Gein isn’t really a serial killer. He murdered two people, which hardly establishes his slayings as a pattern. But he is important because he became a symbol of all the Freudian motivations that we project onto killers. We make these assumptions partly because of the phallic imagery implicit in Psycho’s shower scene or Leatherface’s chainsaw in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Massacre director Tobe Hooper would make a lot of hoopla over Leatherface’s fetish in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, which plays out like a fittingly schizophrenic and limp slasher made by a big Laura Mulvey fan). The funniest part about this scene is that it’s a 100% accurate description of the killer in Frenzy: he tries to rape one of his victims. But she resists and refuses to give him the satisfaction of whimpering while he breathes heavily and repeatedly growls, “Lovely!” The joke is that even McCowen’s chief, an equally impotent British man that politely hems and haws while his wife experiments with French cuisine, could guess why the real killer behaves the way he does. So while most characters in Frenzy spend the film insisting that they know exactly what the cops are looking for, McCowen inexplicably does.

The funniest part about this scene is that it’s a 100% accurate description of the killer in Frenzy: he tries to rape one of his victims. But she resists and refuses to give him the satisfaction of whimpering while he breathes heavily and repeatedly growls, “Lovely!” The joke is that even McCowen’s chief, an equally impotent British man that politely hems and haws while his wife experiments with French cuisine, could guess why the real killer behaves the way he does. So while most characters in Frenzy spend the film insisting that they know exactly what the cops are looking for, McCowen inexplicably does.

When Talking Heads came on the scene in 1975 they were labeled as preppy art punks. This wasn’t entirely by accident. Television, what with their prog-rock leanings, extended guitar solos, and apocalyptic lyrics, were too committed to their music to be mistaken for anything other than a band. But Talking Heads, at least in the beginning, were toying with the idea of what it meant to be a band. When you listen to More Songs About Buildings and Food or Remain in Light you feel challenged, not because you need footnotes in order to understand the songs, but because you know you are listening to a band stretching the possibilities of a pop song while adhering to the rules of pop. Unlike current art-rock outfits like The Fiery Furnaces or Arcade Fire, Talking Heads, for all their conceptual-art trappings, rarely forgot the skill and talent it takes to create a perfect pop song.

When Talking Heads came on the scene in 1975 they were labeled as preppy art punks. This wasn’t entirely by accident. Television, what with their prog-rock leanings, extended guitar solos, and apocalyptic lyrics, were too committed to their music to be mistaken for anything other than a band. But Talking Heads, at least in the beginning, were toying with the idea of what it meant to be a band. When you listen to More Songs About Buildings and Food or Remain in Light you feel challenged, not because you need footnotes in order to understand the songs, but because you know you are listening to a band stretching the possibilities of a pop song while adhering to the rules of pop. Unlike current art-rock outfits like The Fiery Furnaces or Arcade Fire, Talking Heads, for all their conceptual-art trappings, rarely forgot the skill and talent it takes to create a perfect pop song. Filmed in Fort Worth, TX. in support of the Some Girls album, Live in Texas 78 shows the Stones at first looking a little defensive, as if having something to prove. Their previous two albums (It’s Only Rock ‘n Roll and Black and Blue) and tour were met with indifference by everyone except the most hardcore fans. The song “It’s Only Rock ‘n Roll (But I Like It)” was seen as an affront to everything the Stones once stood for. They were now the Establishment. And Punk and Disco were re-invigorating pop music in much the same way the British Invasion did a generation earlier. It almost looked as if The Rolling Stones were no longer relevant.

Filmed in Fort Worth, TX. in support of the Some Girls album, Live in Texas 78 shows the Stones at first looking a little defensive, as if having something to prove. Their previous two albums (It’s Only Rock ‘n Roll and Black and Blue) and tour were met with indifference by everyone except the most hardcore fans. The song “It’s Only Rock ‘n Roll (But I Like It)” was seen as an affront to everything the Stones once stood for. They were now the Establishment. And Punk and Disco were re-invigorating pop music in much the same way the British Invasion did a generation earlier. It almost looked as if The Rolling Stones were no longer relevant.

The central conceit of This Is Not A Film is that it presents a day in Panahi’s life, although I doubt the entire film was actually shot in one day. On a moment-to-moment basis, it feels casually made, but its structure is carefully planned. It depicts him eating breakfast and talking on the phone with his lawyer and fellow filmmaker Rakhshan Bani-Etemad. (She seems to be suffering a period of idleness herself, although it’s unclear if the law has anything to do with it.) When Mirtahmasb shows up, Panahi talks about his unproduced screenplays and reads from one, treating his living room floor as a set. It deals with a teenage girl prevented from attending college and eventually locked in her room by a religious family. Any similarities to Panahi’s current situation are entirely coincidental, of course. Outside, the city of Tehran prepares for Iranian New Year. Fireworks begin going off, and a neighbor asks Panahi to take care of her dog. Eventually, Panahi ventures into the elevator, in the company of the building’s janitor, and the film ends with him apparently on the verge of heading outside.

The central conceit of This Is Not A Film is that it presents a day in Panahi’s life, although I doubt the entire film was actually shot in one day. On a moment-to-moment basis, it feels casually made, but its structure is carefully planned. It depicts him eating breakfast and talking on the phone with his lawyer and fellow filmmaker Rakhshan Bani-Etemad. (She seems to be suffering a period of idleness herself, although it’s unclear if the law has anything to do with it.) When Mirtahmasb shows up, Panahi talks about his unproduced screenplays and reads from one, treating his living room floor as a set. It deals with a teenage girl prevented from attending college and eventually locked in her room by a religious family. Any similarities to Panahi’s current situation are entirely coincidental, of course. Outside, the city of Tehran prepares for Iranian New Year. Fireworks begin going off, and a neighbor asks Panahi to take care of her dog. Eventually, Panahi ventures into the elevator, in the company of the building’s janitor, and the film ends with him apparently on the verge of heading outside.

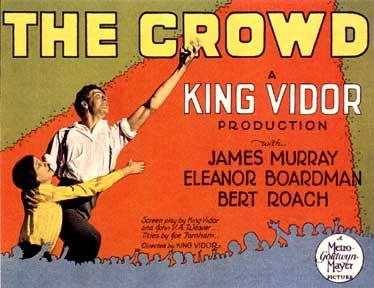

Among the films nominated for Best (Artistic) Picture at that first fabled ceremony was King Vidor's The Crowd. Considered by many to be his masterpiece and a timeless American classic, The Crowd shares many thematic elements to this years Best Picture winner, Michel Hazanavicus' The Artist. Although both film's protagonists have similar trajectories, The Crowd is the opposite of how The Artist presents itself. King Vidor's film was remarkably different for its time in portraying a very non-Hollywood representation of everyday life. While revealing the stylistic influence of his European predecessors, Vidor evoked a natural realism that had not been seen before on American screens. Casting a relatively unknown actor (James Murray) in the lead role of John Sims, he embodied the everyday struggle of a typically average American trying his best to make his mark in a massively foreboding big city. An ambitious, experimental, and socially relevant film, its no wonder why it had been nominated for Best Picture, or why it still resonates today.

Among the films nominated for Best (Artistic) Picture at that first fabled ceremony was King Vidor's The Crowd. Considered by many to be his masterpiece and a timeless American classic, The Crowd shares many thematic elements to this years Best Picture winner, Michel Hazanavicus' The Artist. Although both film's protagonists have similar trajectories, The Crowd is the opposite of how The Artist presents itself. King Vidor's film was remarkably different for its time in portraying a very non-Hollywood representation of everyday life. While revealing the stylistic influence of his European predecessors, Vidor evoked a natural realism that had not been seen before on American screens. Casting a relatively unknown actor (James Murray) in the lead role of John Sims, he embodied the everyday struggle of a typically average American trying his best to make his mark in a massively foreboding big city. An ambitious, experimental, and socially relevant film, its no wonder why it had been nominated for Best Picture, or why it still resonates today.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: It's over! With her inclusion of Best Documentary Shorts in this series, Sarah D. Bunting of

[EDITOR'S NOTE: It's over! With her inclusion of Best Documentary Shorts in this series, Sarah D. Bunting of  The Barber of Birmingham: Foot Soldier of the Civil Rights Movement. A salute to the many men and women who took enormous risks for the movement without needing name recognition, TBoB introduces us to James Armstrong, a barber in his eighties, on the eve of Barack Obama's election. You can't necessarily separate the man from his relationship to the fight for integration (his sons integrated Graymont Elementary in Birmingham), but I'd rather have seen a tighter focus on the man himself, letting those stories come through him. The talking heads and footage of the inauguration made the film a little flat overall.

The Barber of Birmingham: Foot Soldier of the Civil Rights Movement. A salute to the many men and women who took enormous risks for the movement without needing name recognition, TBoB introduces us to James Armstrong, a barber in his eighties, on the eve of Barack Obama's election. You can't necessarily separate the man from his relationship to the fight for integration (his sons integrated Graymont Elementary in Birmingham), but I'd rather have seen a tighter focus on the man himself, letting those stories come through him. The talking heads and footage of the inauguration made the film a little flat overall. Saving Face. This one knocked me back a step. I hadn't known about the epidemic of women getting acid thrown on them in Pakistan, but this horrible problem (if that's a big enough word for it; I feel it isn't) was on the rise. In 2011, a member of the parliament got a bill through that made it punishable with a life sentence, but prior to that, many victims had to continue living with the husbands and in-laws who had maimed them. Others tried to rebuild their lives and self- esteem through plastic surgery and support groups. Some very upsetting footage; a fairly conventional triumph-over-adversity doc, but well done of the genre.

Saving Face. This one knocked me back a step. I hadn't known about the epidemic of women getting acid thrown on them in Pakistan, but this horrible problem (if that's a big enough word for it; I feel it isn't) was on the rise. In 2011, a member of the parliament got a bill through that made it punishable with a life sentence, but prior to that, many victims had to continue living with the husbands and in-laws who had maimed them. Others tried to rebuild their lives and self- esteem through plastic surgery and support groups. Some very upsetting footage; a fairly conventional triumph-over-adversity doc, but well done of the genre.

Current score: Oscars 0, Sarah 61; 24 categories completed

Current score: Oscars 0, Sarah 61; 24 categories completed