Humor can be the cut and the balm—sometimes

Humor can be the cut and the balm—sometimes

one-in-the-same, in the course of a single joke. Sarah Silverman wryly laments: “I was raped

by a doctor, always a bittersweet experience for a Jewish girl.” Wanda Sykes riffs

on how “Black folks, we always have to be dignified, ‘cause if we fuck up, we

just set everybody else back a couple of years. We should have killed Flava

Flav like ten years ago!” A young Joan Rivers does a bit about her mother’s

desperation to marry her off: “Oh, Joan, there’s a man at the door with a mask

and a gun!”

Comedy can also be the hand on the backs of our

necks. Tracy Morgan tells his audience that, if his son came out to him, he’d

stab the boy to death. Daniel Tosh artlessly ponders the fate of a female

heckler: “Wouldn’t it be funny if that girl got raped by, like, five guys right

now? Like, right now?” Joan Rivers serves as the commissioner of the fashion

police: “I took Elizabeth Taylor to Sea World. It was so embarrassing. Shamu

the whale jumps out of the water; she asks ‘does he come with fries?’”

Rivers occupies a complex position in comedy. Her

early work is rightly lauded for its unflinching candor about women’s issues,

and for bringing those issues—the pressure to marry and the tedium of

housewifery, the joys and annoyances of sex, and even abortion—to a national

audience. She is celebrated for serving as the first woman to host her own late

night talk show, and venerated for her tenacity in the wake of tragedy (the

betrayal of her beloved mentor, Johnny Carson; the suicide of her husband and

producer). As a writer and a feminist, I should have called in my own tribute

on the switchboard of Facebook. And yet, I can’t. Rivers’ early work may have

been a slingshot lobbing stones against the powers-that-be, but, in her later years,

her cruelty became a cannon unloading upon the oppressed. She trafficked in

tired slut-shaming and fat jokes.

In perhaps the only way that I will ever be likened

to Elizabeth Taylor, I too have endured my fair share of comparisons to Shamu.

I was a fat girl who became a fat woman, even after dieting and exercising and

binging and purging and taking “nutritional supplements” more potent than 50’s

housewife’s physician-prescribed speed. My fat ass has been the butt of so many

jokes over so many years that I’ve become intimately acquainted with the ways

that “humor” can be used to enforce social codes. Before I was ever aware of

her history, Joan Rivers was that voice that came from the TV in my mother’s

bedroom, a voice that, despite its off-putting raspiness, affected a favorite

wicked aunt chumminess that drew me in until it spit me out: “If Kate Winslet

had dropped a couple of pounds, the Titanic never would have sunk.”

I wasn’t one of those high school girls whose

ticket sales bought James Cameron a summer home, still, I could look up to Kate

Winslet: I would never have her hourglass figure (or her gorgeous red curls),

but her body, and its emancipation from Paltrow thinness, was far closer to

mine than any other modern starlet’s. And there she was on the silver screen,

the real ship of dreams. Ravishing. Desired. So, when Joan Rivers let it rip

with that joke, she was issuing a warning to every fat girl (every girl,

really): There’s only one way to be a woman, and there’s a price to pay for not

looking the part.

This is why,

unlike so many of my peers, I come to bury Joan Rivers, not to praise her.

Rivers famously quipped that, upon her death, her body shouldn’t be donated to

science, but to Tupperware: In truth, all of that plastic has been melted down

and sculpted into an altar to St. Joan of Snark, the groundbreaking vulgarian

who spoke the brutal truths that nice girls were never supposed to say (let

alone in public). Rivers muscled her way to prominence in a male-dominated

field, and she worked steadily for fifty years. It’s no wonder, then, that an

armada of think pieces seeks to defend Rivers as a capital-F feminist (even if

she’d have been reluctant to claim the label for herself). In Time magazine,

Eliana Dockterman equates Rivers’ legendary work ethic and savvy for

self-promotion as an innately feminist endeavor: “Nothing was off-limits as Rivers

wise-cracked her way to the top. And it was this

undisguised and ‘unladylike’ desire for success that made Rivers a feminist

icon.”

Assessments like this

strike me as an uncomfortably corporatized definition of feminism: The will to

work alone does not a feminist make, especially if the work affirms the

structures and mentalities that shame women—for their bodies (though weight was

one of Rivers’ primary comic milieux, she was also free and easy with the word

tranny); their sexualities (and anyone who fell on either side of the

virgin/whore dichotomy was fair game, as evidenced by her cracks about Taylor

Swift’s knees being “together more than Melissa and I” and the Kardashian

sisters needing to find “true love standing up. They’ve had more men land on

them than we’d had in Afghanistan.”); and even for being the victims of

violence (she once said that “those women in Cleveland” had more space in the basement

where they’d been raped and tortured than she had in her daughter’s supposedly

cramped living room; she also joked about slapping Rihanna for possibly

reconciling with Chris Brown).

If her latter-day

humor was particularly vicious toward women, it certainly didn’t spare the

gents. In Rivers’ world, men are shallow dogs following the bone of lithe,

leggy female beauty. They are sexual bullies who don’t see women as people.

They are simultaneously the arbiters of a very specific standard of female attractiveness

and horny devils unable to get it in their pants: “I

said to my husband, ‘Why don’t you call out my name when we’re making love?’ He

said, ‘I don’t want to wake you up.’”

Rivers’ full buy-in to the aesthetic standards that confine

women manifests in more than her stage act; she co-signed with a scalpel. Over

the years, her face attained a stretched-taut surrealness that turned her into

a breathing caricature. There is an unintended but undeniably apt symbolism in

the idea that her natural ability to register and express authentic feeling was

tombed under layers of scar tissue. Her self-loathing, and not her wit, became

her weapon.

As a thirtysomething, I have grown up with the Joan Rivers

who puffed out her cheeks and imitated (her version of) a fat woman’s waddle on

the Letterman Show when discussing Adele, remarking that the latter’s song

“Rolling in the Deep” (which should surely be etched in a Mount Rushmore of

number one pop songs of all time) should be called “Rolling in the Deep Fried Chicken”—diminishing

Adele’s accomplishments as a singer and songwriter by reducing her to a body.

Today’s “Rolling in the Deep Fried Chicken” is yesterday’s “Elizabeth Taylor is

so fat, she has Ragu in her veins.”

As I see these remarks

on list after list of “Joan Rivers’ Best Burns,” I think of Margaret Cho’s

appearance on Rivers’ online interview series In Bed with Joan, and how

their conversation turned to Cho’s body—specifically, how svelte she’d become.

Rivers recalls meeting Cho years prior, when Cho was the anointed It Girl with

a sitcom in the works: “You were a bit of a …” she says, and her pause is the

plank that Cho must walk down before jumping into the deep. A bit of a fat

girl, she admits. Never mind that Cho’s studio-mandated compulsion to lose

weight (and lose it fast) resulted in kidney failure.

Cho may be considered one of Rivers’ heirs apparent, but she

proves that there’s more than one way to be woman who brings a carefully

calibrated cruelty to comedy. Her stand-up is more akin to Rivers’ early work,

bringing a “and fuck you if you don’t like it” bravado to her real talk about

her real pain. Her filth and fury is deployed against the double standards and

the beauty standards that Rivers, in her later years, always endorsed. Cho’s

stand-up film I’m the One that I Want details—with naked rage and

unexpected pathos—her own private Hell-as-a-hamster-wheel of constant dieting:

“I knew I was crazy because I was watching Jesus Christ Superstar and the part where Jesus carries the

cross up the mountain, I actually said to myself, ‘Wow! That must be a really good workout! Yeah, because you’re

doing arms and cardio!’”

She roars and

rampages and names names (including the actual producer whose “concerns” set

Cho on that hamster wheel); still, she shows the kind of woundedness and

vulnerability typically denied to any “nice girl,” in any era, by recounting,

with a necessary explicitness, the physical ravages of all that dieting. She

describes being in the ER, broken and bleeding, and then vaults into an

impersonation of the aggressively earnest nurse who tends to her: “Hi, my name

is Gwen and I’m here to wash your vagina!” This

hyper-attentiveness to the body and its failings (in terms of true mechanical

break-down and in meeting cultural expectations) isn’t just the province of

women.

Much has been written about “And So Did the

Fat Lady,” the episode of Louie that deals earnestly (if not always

successfully) with the stigmatization of fat women; and most of that critique

has focused on the epic monologue delivered by Vanessa, the titular fat

lady—however, the episode also shows how Louie’s hesitance to date Vanessa

stems from his own poor body image and fear of guilt by association (something

that Vanessa even calls him on: “You know, if

you were standing over there looking at us, you know what you’d see? That we

totally match.”). This episode

skewers the contradictions between America’s cult of thinness and the glut of

consumption that comes with a Starbucks on every corner. Louie and his brother

partake in a “bang bang,” a family tradition of going to two different

restaurants (in this case, an Indian place and a diner) and ordering

full-course meals.

Louis C.K. ribs

himself about his weight, but he still shows great tenderness toward his own

fat body. In the season four finale, he takes a romantic bath with his

long-time crush, Pamela; the camera lingers on Louie’s derriere and Pamela

cracks a joke, and yes, when Louie lowers himself into the tub, water sloshes

to the floor, snuffing some of the candles. However, this awkwardness somehow

makes that final moment between Louie and Pamela even sweeter.

Watching Cho and C.K. prompts the question of what

Rivers could’ve done if she’d applied the same tenacity she showed for Liz

Taylor’s waist line to a culture that expects women to be perpetually thin and

everlastingly young. There could be something undeniably powerful in Rivers’

self-abnegation. When so many of our stories about women still hinge on their

prettiness and their experience of being desired, being an outlier to those

desires creates a sense of obliterating isolation. Rivers’ barbs at her own

expense may have come dressed in the baubles and furs of vicious wit, but

underneath those pearls and those stoles there was a naked little heart beating

in sorrow and wrath—and its pulse became a siren song.

Rivers was canny enough to recognize that the

breadth and intensity of her cosmetic surgeries had become a key component of

her celebrity, at times eclipsing her actual body of work. She played herself on

an episode of Nip/Tuck where she implored the plastic surgeon

protagonists to undo all that she’d had done because she wanted her grandson to

see her natural face. She’s horrified by the computer simulation of that

natural face, with all of the lines and wrinkles that anyone lucky enough to

live into their seventies could expect, and she opts for another face lift. The

predictability of this reversal is supposed to be the punchline, but the fact

that a woman with Rivers’ history and influence still views her self-worth

through the prisms of youth and attractiveness is just plain sad.

The difference between Rivers’ quip that her

husband killed himself because she removed the bag over her head during sex (or

that the only she conceived her daughter because her husband rolled over in his

sleep) and Cho’s riff on the producer’s comment about the roundness of her face

(“I had no idea that I was this giant face taking over America! Here comes the

face!”) is that Cho places the shame squarely where it belongs—on our culture,

and its militant insistence on one type of beauty.

Perhaps the most disheartening aspect of what some

could view as Rivers’ artistic decline is that she was once brilliantly,

blazingly capable of taking our culture to task. “I feel sorry for any single

girls today … the whole society is not for single girls,” she says, in a now

widely circulated clip from the Ed Sullivan show. The clip was filmed in 1967,

and Rivers—who looks shockingly girlish, unrecognizable from the woman she’ll

become—speaks directly to those single girls because she was one of them,

peppering her bit with “you know that!” and “isn’t that so? Yes! Yes!” and “it

just kills me!” She rips into the double standards around attractiveness: “a

boy on a date, all he has to be is clean and able to pick up the check … the

girl has to be well-dressed, her face has to look nice, the hair has to be in

shape …” Her take on the pressure to settle down and start a family young (too

young) belongs in a more caustic version of The Bell Jar: “The neighbors

would come over and ask ‘how’s Joan, still not married?’ and my mother would

say ‘if she were alive.’ Do you know how that hurts, when you’re sitting right

there?”

As I watched this clip, still in shock that this

scrappy young woman (the kind of girl I’d want to get drinks with) had ever

become the comic who told women in her audience that they were single because

they were over-educated (“no man will ever put his hand up your dress looking

for a library card”), I thought of how timeless her words remain, of how I

could see them being written in a monologue on Girls, one likely

delivered by Lena Dunham, architect of lines like “So any mean thing someone’s gonna

think of to say about me, I’ve already said to me, about me, probably in the

last half hour.”

I may never be equipped to fully appreciate Joan Rivers;

if, in order to be thankful for her work, I needed to experience a time when

Happy Homemaker was the only role for women and the word abortion was verboten

on TV. She may always be a trailblazer who got stuck in the mud. But I know

that humor can burn and soothe in the same beat: I remember calling a good

friend after I was rushed to the ER with chest pains and palpitations; I told

her that the attending physician warned me off the diet pills, purging, and

starvation unless I wanted “a more severe cardiac incident.” Without pausing,

my friend quipped, “So, you have to choose between your face or your ass or

your heart.” I laughed, and that laugh, however short, was a moment away from my

fear; that laugh acknowledged the untenable position I’d allowed myself to be

put in, because of the things I believed I needed to be.

Laura Bogart’s work has appeared on The Rumpus, Salon, Manifest-Station,

The Nervous Breakdown, RogerEbert.com and JMWW Journal, among other

publications. She is currently at work on a novel.

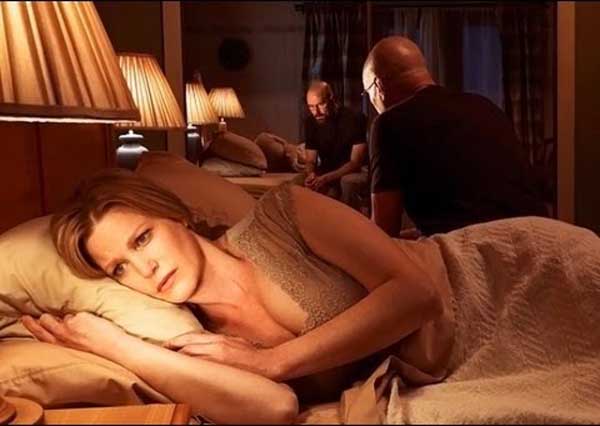

In episode “Fifty-One” of Breaking

In episode “Fifty-One” of Breaking

What do you consider offensive? The dictionary definition of

What do you consider offensive? The dictionary definition of