Between

Between

1987 and 1995, actor, musician, and author Crispin Glover gave America

one of the longest-running and most inscrutable performance art projects

of the postwar era, and did so on one of the largest stages available

to any performer in the States: late-night television. Even now, twenty

years on, the exact nature and purpose of Glover’s project is

unclear–as it’s been deliberately left unclear by its creator–even

though anyone with access to the Internet and YouTube can trace each

stage of the project’s development. What we find, when those individual

and temporally far-flung stages are combined, is an exemplary piece of

“metamericana” that may well have been decades ahead of its time.

*

Crispin

Glover has always been an idiosyncratic and even downright strange man,

and he still is today. In 1987, however, Glover’s quirks were far less

well-known, as besides a forgettable Friday the 13th appearance and a single high-profile role–as the George McFly (both the younger and older versions) in Back to the Future–he’d only been featured in a single movie (River’s Edge) that more than a handful of American moviegoers had seen. And in fact Glover was left off the second and subsequent Back to the Future movies for a reason: he had ideas of being a genuine artist, an ambition of which the director of the Back to the Future

films, Robert Zemeckis, has never been accused. (Zemeckis, among a

number of high-profile, high-grossing thrillers, also produced the Paris

Hilton vehicle House of Wax.)

Though

only 23 in 1987, Glover had already published a novel and performed in

several low-budget art house flicks. He’d also begun writing some

bizarre music that would later feature prominently in his performance

art, which for the purposes of this article I’ll refer to as The Crispin

Glover Project.

*

The Project began in 1987, with Glover’s publication of a novel called Rat Catching. Possibly the first metamodern novel–it was written a decade before David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest—Rat Catching was a pre-Internet remix the likes of which America had not yet seen (at least in its popular culture). What Glover did in Rat Catching

was take a public domain text–a 1896 manual for how to catch and kill

rats–and alternately blacked or whited out large sections of it to

create his own storyline. Sentences were also rearranged at will, and

captions to the many pictures included in the original manual were

altered; finally, Glover’s name was sloppily affixed to the title page

over the name of the original author.

Rat Catching

is an astounding and disturbing book, one that simultaneously

deconstructs an existing text and constructs from it a new and only

partially related one. It juxtaposes deconstruction and construction in a

single “reconstructive” literary act. Importantly, the novel was

eminently readable, even if the purpose behind its deconstruction of a

rat-catching manual–or even the purpose of the novel Glover replaced

that manual with–was unclear. Rat Catching was therefore not so

much a degradation of language conducted with a political point in

mind–as is typically in the case with work we identify as

“postmodern”–but a re-purposing of language made with no obvious

critique in mind, or at least no evident critique, but only the desire

to create something new and unforgettable.

At the same time that Rat Catching was being published, Glover was finishing up work on Rubin and Ed,

a low-budget film that (unbeknownst to Glover at the time) wouldn’t be

released for several more years. It was in this context that Glover made

his first appearance on the David Letterman show, an appearance still

regarded as one of the strangest five minutes in television history.

*

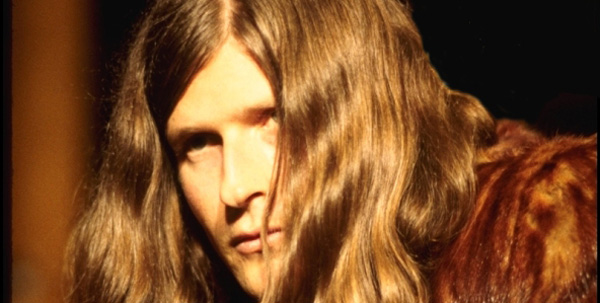

On

July 28, 1987, Glover, sporting glasses, unusually long hair, and

platform shoes, conducted a five-minute interview with Letterman–if it

could be called that–before Letterman walked off the set in both

disgust and (he would later indicate) a fear for his personal safety.

Here’s a clip of Glover’s first appearance on Late Show with David Letterman:

Note

that Glover answers most questions while looking into an unknowable

middle distance, seems either scared or anxious (it’s not clear which),

and begins his descent into outright lunacy only after a woman in the

audience–many now believe her to have been a plant–begins heckling

him. “Nice shoes!” the woman shouts, and everything quickly deteriorates

into madness.

In

the early stages of his "breakdown," Glover seems to be raising the

question of how the media covers celebrities (he takes out a wrinkled

newspaper clipping to opine about it, and certainly appears to be

dressed as someone other than the celebrity he was and is) but at no

point does any real commentary or critique materialize. What Glover

does, instead, is nearly fall off the stage and then execute a possibly

impressive and certainly violent-looking karate kick.

After

a commercial break, Glover is nowhere to be seen; Letterman implies he

was kicked off the set. Letterman’s bandleader, Paul Schaffer,

speculates–in a moment of (for him) unusual candor and insight–that

the whole event was a “conceptual piece.” Letterman isn’t so sure, and

seems genuinely put off by Glover.

Nevertheless, he agrees to have him back on the show a second time.

*

Glover’s

second visit to Letterman’s program was as strange as the first, but in

an entirely different way: Glover is meek, harmless, and giggling, in

fact giggles so frequently that–coincidentally–he never has to answer

any of the host’s questions about his first appearance on the program.

The

short version of what’s happening: Glover, again without Letterman’s

knowledge–let alone permission–is controlling the interview. He does

so in a way that’s so confusing to the audience that they start booing

Letterman, not Glover, when the former makes repeated fun of the

latter’s demeanor, twice threatens to assault his guest, and repeatedly

implies that he’s about to throw Glover off the show again.

As

you can see in the video above, when Letterman asks Glover to explain

his first appearance, Glover refuses to say whether the clothes he wore

during the appearance were his “real” clothes or merely props. He

giggles uncontrollably and asks Letterman, “Well, what did you get [from

it]?” when the host asks him to explain his previous visit. And yet, as

odd as Glover’s words seem, everything he says to Letterman could

readily serve as a description of one brand of metamodern art: that

being metamodern art inspired by the writings of university professor

Mas’ud Zavarzadeh, who coined the term “metamodernism” in 1975:

Says Glover:

(1) “It’s self-explanatory…kind of…”

(2) “There it was, or there it is…”

(3) “I feel like I shouldn’t say anything [about it]…”

(4) “I wanted it to be this interesting kind of thing that would happen that people would find interesting…”

(5) “The point…was [to create] interest…”

(6) “It was going to go to a different point…it wasn’t going to escalate, it was going to go down into a newer [sic] state…”

Letterman,

literally leaning forward in his chair to get an answer to his

questions, never gets any answer at all. “What was the point?” he asks

Glover repeatedly. But Glover, who in fact was not then (and is not now)

an obsessive giggler, and who’s widely perceived as an intellectual and

creative genius by his peers and many fans, offers no answer because

the answer is already right in front of Letterman and the audience:

Glover has used language and bodily performance to get and keep the

attention of an audience, but has done so without any evident purpose in

mind. He shows Letterman, that is, that attention is the currency of

contemporary America–a maxim that would be infinitely enhanced in

veracity and utility after the popularization of the Internet–and that

the primary value of the most successful attention-seeking art is not

that it critiques language or culture through Modernist constructions or

postmodernist deconstructions, but that it removes viewers from their

own lived realities.

When

Glover asks Letterman, “Did you find it interesting, in one way?”,

Letterman shakes his head “no.” Yet that answer is belied by the fact

that the host invited back his troublesome guest just days after his

first appearance–and would invite him back repeatedly afterwards.

Glover is so interesting to Letterman that his interest manifests as an

intense aversion he associates with disinterest.

We

see the same phenomenon at play on the Internet today: we follow and

discuss with an eerie obsession those we claim to dislike and even be

viscerally put off by; we give additional attention to people we

consider superfluous by way of writing at length about how they deserve

no attention; we follow types of art we detest with an even greater

intensity of attention than those we claim to be enamored by; we even

write critiques of that art in which we simultaneously claim that it has

no effect on its audience and note that everybody just can’t stop

talking about it. Again and again we see art that seems higher-brow and

more intricate and laud its qualities and even, specifically, its

memorability–but see no self-contradiction in our analysis when it

later fails to excite much ongoing attention at all. It’s almost as

though we know very what type of art finds clever ways to gain and hold

attention in the Internet Age, but need to half-heartedly construct

narratives in which we assure ourselves that it’s otherwise.

In

other words, when we encounter metamodern art or personalities we often

unwittingly consume the very paradoxes they and their art perform.

*

Every

episode of Letterman’s program, for decades, has been either funny or

not, either instructive or not, either “real” or “staged,” either “good

TV” or “bad TV”–except

for those nights Crispin Glover has appeared on the program, and the

few times that others interested in Glover’s creative vision have aped

his methods in the same venue.

The Crispin Glover Project was designed to overleap poles of thought and affect like “real” or “staged” in order to

create a space in which all poles are simultaneously present and

absent. Glover’s performances on Letterman are both funny and not, and

therefore end up being neither; they feel like bad television but have

the staying power all good television has; they’re ambivalent on the

question of whether they’re “real” or “staged,” and for this reason are

impossible to forget. After all, we tend to remember those experiences

that most wrench us from the known and comforting–often calling these

experiences “sublime”–and the Crispin Glover Project was intended to

show that concept-driven art can create these experiences better than

any other method.

*

Glover

believes, as do a certain strain of metamodernists, that in the

Internet Age the most important civic quality we can all develop is an undirected attentiveness--a

paradoxical state in which we’re ready to believe things and act on

beliefs that are normally outside our experience of the world. If we can

learn to be most attentive in those moments we’re most out of our

comfort zones, we can begin acting in the world in a way that isn’t

bound by the same conventional thought that hasn’t worked out for many

of us in the past. We might therefore call Glover’s apolitical art

“preparatorily political.”

When

Glover ends his second appearance on Letterman by showing the host a

series of art objects that make no sense whatsoever, both Letterman and

the audience are rapt: not because what they’re looking at is garbage,

but because they don’t even know what they’re looking at–and Glover’s

explanations of each object are just plausible-seeming nonsense. If

postmodern deconstruction asks us to so minutely dissect meaning and

performance that there’s literally no end to the levels of precision and

distinction we can produce, Glover’s metamodern art asks us to do

precisely the opposite: accept that there are things we cannot know or

understand, but see also that this "not-knowing" can, paradoxically, be a

powerful preparation for future action.

In

Glover’s third appearance on Letterman’s program, much like during his

second one, he giggles and stutters demonstrably less the moment he’s

asked about his current art projects instead of the The Crispin Glover

Project. In fact, not only does Glover dress “normally” for his 1990

interview with Letterman–continuing his trend of dressing progressively

more conventionally with each appearance–but in fact only stutters or

giggles whenever Letterman asks him about a topic he wishes to avoid.

When speaking of other projects, Glover acts as any other guest might,

and speaks with great clarity and focus. But one thing he doesn’t

do is answer any of Letterman’s questions about the Project; instead,

he deliberately runs out the clock on his segment by telling a story

that superficially might, but also might not, have anything to do with

his first appearance on the program. And once again, Letterman gets

booed on his own show for his abrupt treatment of his guest.

The

above video is worth watching not only for Glover’s continuation of his

performance art project, but also because it marks the debut of “Clowny

Clown Clown,” a Glover song–with accompanying video–that is neither

"understandably bad" to the point it can be made fun of, nor good enough

to admire. Instead, like the rest of the Project, it’s basically

inscrutable. It deconstructs linear narrative into incoherence, but does

so with such a naive commitment to creation and self-expression that it

seems every bit as Modern as it is postmodern. The crowd loves it, and

boos Letterman when he calls Glover “Eraserhead” at the close of the

interview.

Here’s the full music video for “Clowny Clown Clown”:

Listen

to the song without watching the video and you’ll see that, in fact,

it’s just a rather silly but conventional (and in fact linear)

narrative. The lyrics even make mention of “Mr. Farr,” the character

Glover may have “played” during his first Letterman interview. “Thinking

back about those days with the clown,” sings Glover toward the end of

the song, “I get teary-eyed–and snide. I think, deep down, ‘I hated

that clown. But not as much as Mr. Farr.’” The meaning here isn’t hard

to interpret at all, despite the video’s attempts to make it seem

opaque. (A reasonable read would be that Glover is speaking of the three

roles he plays: the “I” is Glover, the “clown” is

Glover-as-performance-artist, and “Mr. Farr” stands in for one of the

many Hollywood acting jobs Glover has taken on. Glover hates not being

able to be himself in public, but he’d rather act the clown–someone

simultaneously midway and "beyond" his actual and acting selves–than

merely be remembered for the characters he’s played on screen.)

*

The coda to the Project is Glover’s last performance art-related appearance on Letterman,

in 1992. Again Glover refuses to justify or explain his first

appearance on the program, or even to tell the host whether he was

wearing a wig on that (by now) infamous night. “Why can’t you just

answer this?” asks an agitated Letterman. “I mean, if it’s a wig, it’s

fine, but if it’s not a wig, it’s fine. Either way.” In fact,

Letterman’s need to know the answer suggests that he can accept either

of two opposite possibilities–a sign of maturation on Letterman’s

part–but that he still can’t accept not knowing whether either of these

possibilities is the “real” answer to his question. “Sure, it is fine,” says Glover, refusing to say more.

The

most telling statement by Glover in the video above is this one: “I

like to leave it…mysterious. Well, here’s the facts: I’m wearing a wig

in the movie [Rubin and Ed], and I look exactly the same in the

movie as I did when I was on the show.” Though Letterman acts as though

his interrogation has yielded fruit, in fact this is yet another

non-answer: Glover merely restates the facts as everyone agrees them to

be, refusing to either deconstruct or synthesize them on anyone else’s

behalf.

*

In

all of this, we have to remember the behavioral oddities of the role

that made Glover famous, and for which he’s still best known today:

If

you’ve watched the video above, you’ve probably noticed the key to The

Crispin Glover Project, which is that, by and large, the entirety of the

Project comprises Glover performing an amplified version of George

McFly in public. For years.

Here, below, is Glover as he actually

is, explaining to two radio hosts what acting as George McFly–and

being remembered almost exclusively for that role–taught him about

propaganda:

Per Glover, Zemeckis was able to convince viewers of Back to the Future II

of a lie–that Glover was in the film, when in fact he was not–simply

by giving them what they expected to see. In response, Glover found a

way to use the very same character Zemeckis was manipulating to give

viewers of David Letterman’s television show something they couldn’t

possibly expect. One might even say that Glover offered America the

opposite–in both form and effect–of propaganda. (He also, in an

interesting historical note, sued Zemeckis for misuse of his image–and

won.)

Now

here’s Joaquin Phoenix stealing Glover’s idea nearly twenty years later

and (in a show of real gall) doing so on the very same television

program:

And

here’s the most talked about celebrity in America right now, Shia

LaBeouf, wearing exaggeratedly ragged clothing and stealing from Joaquin

Phoenix stealing from Crispin Glover:

It’s

no coincidence that LaBeouf’s seeming point is the same one we might

glean from Glover’s project: that new media destroys, if we permit it

to, both the reality-artifice spectrum and many other polar spectra

besides. Which frees us to free ourselves from these limiting spectra as

well.

Over

the next twenty years, we’ll hear a lot about art that is

simultaneously sincere and ironic and neither, naive and knowing and

neither, optimistic and cynical and neither. While two of the theorists

presently associated with metamodernism, Tim Vermeulen and Robin van den

Akker, originally described such art as “oscillating” between

conditions traditionally associated with Modernism and

postmodernism–for instance, sincerity and irony, respectively–their

view has changed in recent months. Now, they, and other metamodernists,

are more likely to note that metamodern art permits us to inhabit a

“both/and” space rather than merely the “either/or” spaces deeded us by

the “dialectics” of postmodernism.

“Both/and” means transcending

the poles that have been thought to dominate our lives ever since Plato

devised the term "metaxis" to describe this condition of moving

perpetually between opposites. By comparison, “either/or” means that

everything is a zero-sum game and can never be otherwise. On online

discussion boards, for instance, "either/or" dialectics prompt us to

believe that others can only agree with us or oppose us, to understand

us in our entire selves or be deliberately and permanently foreign to

us; there’s no room for partnerships in which not all perspectives are

shared, let alone partnerships in which participants’ goals but not

their values are in common.

If the ultimate ambition of metamodern art, and metamericana generally,

is to help us discover what the “and” in “both/and” could possibly

mean, we must credit Glover with being one of the pioneers in that

historically important search.

Seth Abramson is the author of five poetry collections, including two, Metamericana and DATA,

forthcoming in 2015 and 2016. Currently a doctoral candidate at

University of Wisconsin-Madison, he is also Series Co-Editor for Best American Experimental Writing, whose next edition will be published by Wesleyan University Press in 2015.

Back in the early 2000s, a friend and I worked together on

Back in the early 2000s, a friend and I worked together on

Back in October 2013, an episode of The Big Bang Theory ruined Raiders

Back in October 2013, an episode of The Big Bang Theory ruined Raiders

In the first season of Transparent,

In the first season of Transparent,

Between

Between

The places where we live shape us, and we shape the places

The places where we live shape us, and we shape the places

In my

In my